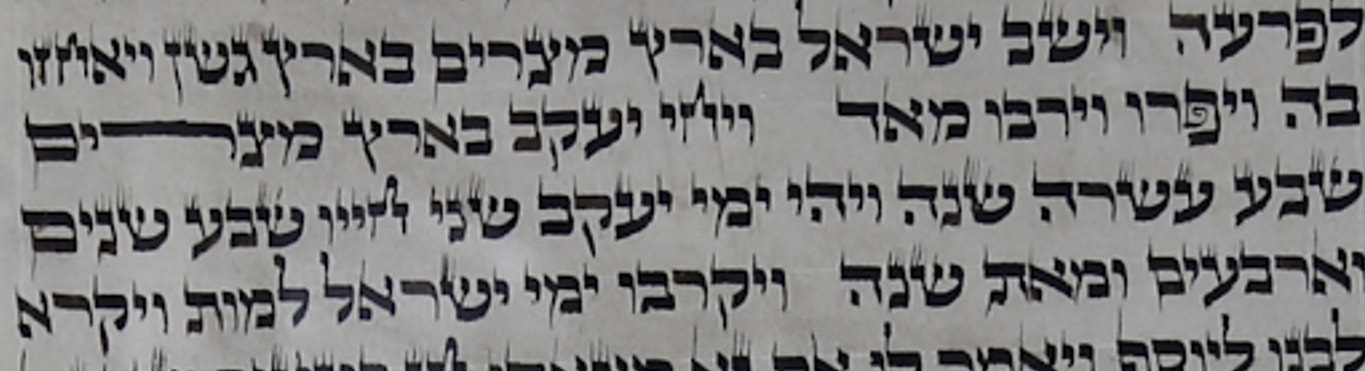

Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Shoshana Elka bat Avraham, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Peretz ben Chaim, Chaya Sarah bat Reb Yechezkel Shraga, Shmuel Yosef ben Reuven, the Kedoshim of Har Nof, Pittsburgh, and Jersey City, and the refuah shlaimahof Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, Moshe ben Itta Golda, Yocheved Dafneh bat Dinah Zehavah, Reuven Shmuel ben Leah, and the health and safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Ezra the Scribe (5th century BCE) was one of the great leaders of the Jewish people. One of his most significant achievements was the establishment of the exact format in which a sefer Torah must be written. Our parasha contains an outstanding example of his handiwork. At the beginning of all other parshiot in a Sefer Torah, there is a clear indication that a new Torah portion is about to begin, separate from the previous one. This is not the case in our sidrah,which leads Midrash Bereishit Rabbah and Rashi (1040-1105) to ask: “Lamah parasha zu satumah?” (“Why is this Torah portion completely closed?”) The Siftei Chakhamim (Rabbi Shabbeti Bass, 1641-1718) explains the substance of this question in the following manner: That is to say, we have a tradition from Ezra the Scribe, may he rest in peace, that Parashat Vayechi [beginning with the word “vayechi” itself] is the beginning of an entirely new section and not conjoined to the preceding parasha [that concludes] with the verse “vayeshev Yisrael…” [Parashat Vayechi, however,] does not follow the standard form of a parasha satumah, since [such a section normally has a blank space in front of it] that equals the size of nine letters, yet, in our case, the entire beginning of the parasha is totally closed without any space whatsoever. (Commentary on Rashi’s gloss, Sefer Bereishit 47:28, translation my own) Although Midrash Bereishit Rabbah offers three answers to the question, “Lamah parasha zu satumah,” the Kli Yakar (Rabbi Shlomo Ephraim ben Aaron Luntschitz, 1550-1619) summarily rejects each of them and states: “It certainly appears that there is no support whatsoever from the Torah’s text for any of these interpretations; as such, they are like false prophecies.” (Sefer Kli Yakar, Parashat Vayechi 47:28, this and the following translations my own). This leads him to surmise that even though Parashat Vayechi and Parashat Vayigash are two separate parshiot, it is: incontrovertibly the case that Ezra the Scribe’s intention [in writing Parashat Vayechi completely satumah] was to have the verse beginning with vayechi juxtaposed to the preceding verse [from Parashat Vayigash] in order for the two pasukim to be read as: “And Israel dwelt in the land of Egypt in the land of Goshen, and they acquired property in it, and they were prolific and multiplied greatly. And Ya’akov lived in the land of Egypt for seventeen years…” as if they were actually one verse. (47:27-28, this and all Tanach translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach, Kli Yakar translations my own) At this juncture, the Kli Yakar utilizes this “extended verse” concept to revisit and reinterpret the first answer Midrash Bereishit Rabbah provides to the question lamah parasha zu satumah, namely, “When Ya’akov died, shibud Mitzrayim (Egyptian servitude) began.” In so doing, he offers two approaches to the relationship between Ya’akov’s death and the onset of the shibud: Initially the text states, “And Ya’akov lived in the land of Egypt for seventeen years,” and teaches us through the utilization of the word, “vayeshev” (lived) that the Jews at that time dwelt in peace and tranquility, so much so that they were able to acquire significant landholdings in Egypt and greatly expand their population. All of this took place during the time of, “and Ya’akov lived,” for during his lifetime each member of the Jewish community directly benefitted from zechut Ya’akov (the merit of Ya’akov). From here we may infer that his zechut ceased upon his death, and so, too, all the positive outcomes it had engendered...And, according to this line of thought, Ya’akov’s death caused the onset of the Egyptian servitude. In sum, according to this view of the Kli Yakar, Ya’akov’s death ended the golden age described in 47:27-28, when our forebears “dwelt in peace and tranquility.” In addition, as he clarifies in further comments, the fledgling Jewish people then ceased being landowners and became enslaved to the Egyptians who strived to embitter their lives. In short, Ya’akov’s death precipitated shibud Mitzrayim. The Kli Yakar takes the polar opposite tact in his second analysis of the juxtaposition of the last verse of Parashat Vayigash and the first pasuk of our parasha. In this scenario, rather than Ya’akov’s death triggering shibud Mitzrayim, shibud Mitzrayim led to Ya’akov’s death: And it is possible to say exactly the opposite, namely, the beginning of the servitude was the reason for his death, as the Holy One blessed be He shortened the years of his life so that he did not live as long as his fathers [that is, Yitzchak and Avraham] in order for him to be spared seeing his children in bondage, for the time had now arrived [as foretold to Avraham] of “and they will enslave and oppress them for four hundred years.” (Sefer Bereishit 15:13) I believe that the Kli Yakar is intimating something quite fascinating regarding Ya’akov Avinu’s persona. Our standard perception of Ya’akov is as ish tam yosheiv ohelim (Sefer Bereishit 25:27, the pure and innocent individual who dwelt in the tents of Torah), who represented the highest heights of truth, as we find in the celebrated verse: “You shall give the truth of Ya’akov, the loving-kindness of Avraham, which You swore to our forefathers from days of yore.” (Sefer Michah 7:20) As such, we rarely focus upon the emotional sensitivities that infused his being. Yet, the Kli Yakar is teaching us that Ya’akov simply would have been unable to bear seeing his children suffer in abject slavery; therefore, the Master of the Universe mercifully allowed him to die before his time, to spare him from witnessing such heart-wrenching scenes. In a very real sense, we can now understand why Ya’akov was the perfect husband for Rachel, for they were united in their empathy for the pain and anguish of the Jewish people. As the verse states: “So says the L-rd: A voice is heard on high, lamentation, bitter cries, Rachel weeping for her children, she refuses to be comforted for her children for they are no more.” (Sefer Yirmiyahu 31:14, with my emendations) May the time come soon and in our days when Rachel will no longer weep for her beloved children and Ya’akov will no longer fear for our physical and spiritual welfare, a time when we will be blessed with true shalom al Yisrael. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom, and may Hashem in His infinite mercy remove the pandemic from klal Yisrael and from all the nations of the world. V’chane yihi ratzon. Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org using the search criteria Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

AuthorTalmid of Rabbi Soloveitchik zatzal Categories |

- Blog: Rabbi David Etengoff: Parashat HaShavuah

- Sefer Bereishit 5784&5785

- Sefer Shemot 5784&5785

- Sefer Vayikra 5784&5785

- Sefer Bamidbar 5784 &5785

- Sefer Bereishit 5782&5783

- Sefer Shemot 5782&5783

- Sefer Vayikra 5782&5783

- Sefer Bamidbar 5782&5783

- Sefer Devarim 5782&5783

- Sefer Bereishit 5780& 5781

- Sefer Shemot 5780&5781

- Sefer Vayikra 5780&5781

- Sefer Bamidbar 578&5781

- Sefer Devarim 578&5781

- Sefer Bereishit 5778&5779

- Sefer Shemot 5778&5779

- Sefer Vayikra 5778&5779

- Sefer Bamidbar 5778&5779

- Sefer Devarim 5778&5779

- Sefer Bereishit 5776&5777

- Sefer Bereishit 5774&5775

- Sefer Bereishit 5772&5773

- Sefer Bereishit 5771&5770

- Sefer Shemot 5776&5777

- Sefer Shemot 5774&5775

- Sefer Shemot 5772&5773

- Sefer Shemot 5771&5770

- Sefer Vayikra 5776&5777

- Sefer Vayikra 5774&5775

- Sefer Vayikra 5772&5773

- Sefer Vayikra 5771&5770

- Sefer Bamidbar 5776&5777

- Sefer Bamidbar 5774&5775

- Sefer Bamidbar 5772&5773

- Sefer Bamidbar 5771&5770

- Sefer Devarim 5776&5777

- Sefer Devarim 5774&5775

- Sefer Devarim 5772&5773

- Sefer Devarim 5771&5770

RSS Feed

RSS Feed