Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon HaKohane, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Gittel Malka bat Moshe, Alexander Leib ben Benyamin Yosef, the Kedoshim of Har Nof, Pittsburgh, and Jersey City, the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, and the health and safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The protagonist of this week’s haftorah is the prophetess and judge Devorah: “Now Devorah was a woman prophetess, the wife of Lappidot; she judged Israel at that time.” (Sefer Shoftim 4:4, this and all Tanach and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Chazal teach us in Talmud Bavli, Megillah 14a, that Devorah was one of the seven prophetesses: “Who were the seven prophetesses? Sarah, Miriam, Devorah, Chana, Avigail, Chulda, and Esther.” It appears, as well, that she had the additional distinction of being one of the Judges (Shoftim) of the Jewish people—if we take the phrase, “she judged Israel at that time” (“hi shoftah et Yisrael ba’eit hahi”) at face value. It seems that the phrase, “she judged Israel at that time,” should be understood in its literal sense, as the next pasuk states: “And she sat under the palm tree of Devorah, between Ramah and Beth-El, in the mountain of Ephraim; and the children of Israel came up to her for judgment.” (Sefer Shoftim 4:5) There is a fundamental halachic problem with this interpretation, however, since the fourth century Talmud Yerushalmi, Yoma 6:1 (32a) states: “… a woman may not judge” (“ain haisha danah”). Although the Rambam (1135-1204) does not explicitly include this ruling in his Mishneh Torah, it is found nearly verbatim in the Arba’ah Turim of Rabbi Yaakov ben Asher (1270-1340), and in Rabbi Yosef Karo’s (1488-1575) Shulchan Aruch, Choshen Mishpat, Hilchot Dayanim 7:4: “A woman is disqualified from judging” (“ishah pasulah l’don”). Given this clear-cut ruling, we must ask the simple and straightforward question: “Was Devorah really a judge?” The answer, as in many areas of halacha and hashkafah, is a resounding, “It depends on who you ask.” Tosafot discuss Devorah’s status in a number of different tractates of the Talmud. One such source is Talmud Bavli Gittin 88b s.v. v’lo lifnei hedyotot. Initially, Tosafot opines that the phrase from Sefer Shoftim “she judged Israel at that time,” should not be taken literally, since it may very well mean “… perhaps she never rendered judgment at all, and [instead] she instructed [the judges] as to what the legal decisions ought to be.” (This, and the following Tosafot translation of this source, my own) According to this view, although Devorah was a legal scholar who discussed cases with members of various batai din (Jewish courts), she was not an actual judge. It should be noted that this approach is followed by Rabbi Yaakov ben Asher in the above-cited section of the Arba’ah Turim. In contrast, Tosafot’s second approach suggests that Devorah was a practicing judge, and her mandate to adjudicate cases came directly from the Almighty: “Alternately, perhaps they [the Jewish people] had accepted her judicial authority upon themselves because of [a Divine pronouncement] from the Schechinah (Hashem’s immanent presence).” Devorah as a judge in practice—based upon Divine mandate—finds further support in Talmud Bavli, Megillah 14a, in one of the explanations of the phrase, “And she sat under the palm tree of Devorah:” “Just as this palm tree has but one heart [Rashi: “a central growing point”], so, too, did the Jewish people of that generation have but one heart (lev echad) directed to their Father in Heaven.” This explanation is particularly fascinating in that Devorah’s universal acceptance as a judge for klal Yisrael (the Jewish people) took place precisely because the heart of the Jewish people was unanimously directed to avinu she’b’shamayim (our Father in Heaven). Chazal’s use of the term, lev echad, is reminiscent of Rashi’s gloss in Parashat Yitro on a celebrated phrase that precedes Kabbalat HaTorah (the Receiving of the Torah). Therein the Torah states: “and the Jewish people encamped (va’yichan Yisrael) there opposite the mountain.” (19:2) Rashi focuses on the word, “va’yichan,” and notes that it is in the singular, rather than the plural, even though it refers to the entire Jewish nation. Consequently, he suggests this term connotes: “K’ish echad b’lev echad—like one man with one heart—but [that is, even though,] every other encampment was marred by complaints and arguments.” In sum, our ancestors were united, and stood shoulder to shoulder in anticipation of receiving the Torah in order to serve avinu she’b’shamayim, just as they would in the time of Devorah HaNaviah. The message is clear: When we have achdut (unity) and a desire to draw closer to the Holy One blessed be He, then there is nothing that we cannot accomplish as a people. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org. Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav

0 Comments

Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon HaKohane, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Gittel Malka bat Moshe, Alexander Leib ben Benyamin Yosef, the Kedoshim of Har Nof, Pittsburgh, and Jersey City, the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, and the health and safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Parashat Bo continues the Torah’s emphasis on events leading up to Yetziat Mitzraim (the Departure from Egypt) that began in the prior two parshiot of Sefer Shemot. At this juncture, we are introduced to two mitzvot that portray the singular import of the Exodus: The first is the mitzvah of Zechirat Yetziat Mitzraim (13:3), the obligation to remember and mention the Exodus, and the second is the mitzvah of Sippur Yetziat Mitzraim, the recounting of the story of the Departure from Egypt (13:8). The 13th century anonymous author of the Sefer HaChinuch, a work that analyzes the Taryag Mitzvot (the 613 Commandments), begins his discussion of Sippur Yetziat Mitzraim with this formulation: The commandment to recount the Exodus from Egypt: To retell the story of the Exodus from Egypt on the night of the fifteenth of Nissan—each person according to their power of expression—to laud and to praise Hashem, may He be blessed, for all the miracles He performed for us there, as it is stated, “V’he’gaddatah l’vinchah… (“And you shall tell your son,” Sefer Shemot 13:8),” translation with my emendations, https://www.sefaria.org/Sefer_HaChinukh.21.1?lang=bi) The Sefer HaChinuch does not discuss Zechirat Yetziat Mitzraim, since it is nearly universally accepted among the Monei HaMitzvot (Compilers of the Taryag Mitzvot) that it is not counted among the 613 Commandments. In contrast, Rashi (1040-1105), in his gloss on the phrase, “zachor et hayom hazeh asher y’tzatem m’mitzraim (remember this day, on which you left Egypt, Sefer Shemot 13:8),” makes it clear that this statement represents a mitzvah of the Torah. Basing himself upon Midrash Mechilta d’Rabbi Yishmael, Parashat Bo 16, he explains “This teaches us that we have a daily [obligation] to mention the Exodus from Egypt.” My rebbe and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal (1903-1993), known as “the Rav” by his students and followers, supports Rashi’s reading and notes that “regarding the truth of the matter, the mitzvah [that is, the daily obligation to mention the Exodus] was really stated in the verse, ‘zachor et hayom hazeh.’” (Shiurim l’Zacher Abba Mori, II, page 152, translation and brackets my own) It is clear that the mitzvot of Zechirat and Sippur Yetziat Mitzraim are firmly based upon pasukim in our parasha. Yet, if the Torah commands us to remember and mention Yetziat Mitzraim, why are we also obligated in the mitzvah of Sippur Yetziat Mitzraim? To borrow from the language of the Haggadah: Mah nishtanah mitzvat Zechirat Yetziat Mitzraim m’mitzvat Sippur Yetziat Mitzraim (What is the difference between the mitzvah of Zechirat Yetziat Mitzraim and Sippur Yetziat Mitzraim)? The Rav states that his father, HaRav Moshe Soloveitchik zatzal (1879-1941) shared the opinion of his father, HaRav Chaim Soloveitchik zatzal (1853-1918) on this matter, and noted four differences between these two mitzvot:

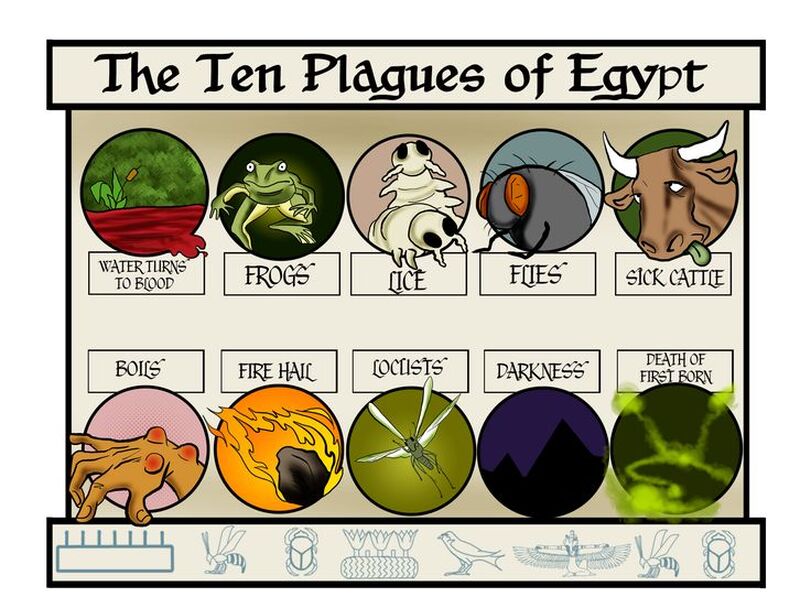

The Rav added another distinction: The obligation of remembering does not require a person to proclaim praise and thanks [to the Almighty,] whereas, Sippur Yetziat Mitzraim is not only [an act] wherein we recite the wonders and miracles that were done for us, rather, we have the additional responsibility to give praise and thanks [to Hashem] … (Shiurim l’Zacher Abba Mori, I, page 2, translation and brackets my own) Whenever we recite Kriat Shema, we have the opportunity to fulfill the mitzvah of Zechirat Mitzraim. May the Almighty help us do so with kavanah (focus and intent) and may this spiritual awareness lead to a powerful recognition of the wonders and miracles He performed for us at that time, enabling us to praise and thank Him when we recount the story of Yetziat Mitzraim. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org. Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon HaKohane, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Gittel Malka bat Moshe, Alexander Leib ben Benyamin Yosef, the Kedoshim of Har Nof, Pittsburgh, and Jersey City, the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, and the health and safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Pesach, the most widely observed chag of the Shalosh Regalim, is preeminently the time when families and friends join together at the Seder and recite the Haggadah. One of the many highlights of this experience is the presentation of the Eser Makkot (Ten Plagues), which have become one of the most celebrated aspects of the Pesach story. Precisely because they are so well-known, however, there is a danger that some among us may lose sight of their miraculous nature. As we find in Pirkei Avot: “Ten nissim (miracles) were performed for our forefathers in Egypt… Ten makkot were wrought by G-d upon the Egyptians in Egypt.” (5:4, translation, Rabbi Yosef Marcus with my emendations) The first seven makkot are found in our parasha, and the final three in Parashat Bo. As such, the time of these Torah readings is an ideal opportunity to ask ourselves, “Since the Master of the Universe could have visited any kind of plague upon the Egyptians, why did He choose precisely these ten?” A revealing answer is found in the midrashic work, Seder Eliyahu Rabbah: The Holy One blessed be He brought ten plagues upon the Egyptians; and all were brought upon them solely as a result of what they planned to do, [and did against,] the Jewish people. This is the case, since the words [and deeds] of the Holy One blessed be He are absolute truth and operate with the principle of middah k’neged middah (measure for measure). Therefore, no evil action goes forth from Him, only good (that is, fitting) actions. Moreover, [seemingly] negative behaviors are actualized against people, [as in the case of the Eser Makkot,] as a result of their twisted and perverse actions … (7:8, this and the following translation and brackets my own) In sum, each of the Eser Makkot is a middah k’neged middah response by the Almighty to the evil behaviors of the Egyptians against our people. A particularly telling proof of this concept is offered by this midrash (7:15) in its analysis of Makkat Barad (the Plague of Hail): Why was barad brought upon them? This is because the Egyptians forced the Jewish people to plant gardens, orchards, [vineyards] and all manner of trees. [They forced them to undertake this activity] to prevent them from returning to their homes so they would be unable [to engage in marital intimacy and bring forth] more children. Therefore, the Holy One blessed be He brought the Plague of Hail upon them that destroyed all the plantings in which the Jewish people had been engaged. As the texts state: “He destroyed their grapevines with hail…” (Sefer Tehillim 78:47) … “the hail struck all the vegetation of the field, and it broke all the trees of the field.” (Sefer Shemot 9:25) The barad sent by the Almighty was completely beyond the Laws of Nature: “And there was hail, and fire flaming within the hail, very heavy, the likes of which had never been throughout the entire land of Egypt since it had become a nation.” (Sefer Shemot 9:24, this and the following Tanach and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach). Rashi (1040-1105), basing himself on Midrash Tanchuma 14:10, develops this theme by noting the nase b’toch nase (miracle within a miracle) composition of the barad: “[This was] a miracle within a miracle. The fire and hail intermingled. Although hail is water, to perform the will of their Maker they made peace between themselves [so that the hail did not extinguish the fire nor did the fire melt the hail].” In addition, Midrash Tanchuma brings a mashal (parable) to help us grasp the meaning of this unique double nase: To what may this be compared? To two powerful legionaries who have despised each other for a long time. When their king became involved in a war, he made peace between them so that they would go forth together to fulfill the king’s command. Similarly, though fire and hail are hostile to each other, when the time for war with Egypt came, the Holy One, blessed be He, made peace between them and they smote Egypt. Hence it is said: “The fire flashing up amidst the hail.” When an Egyptian was seated, he would be pummeled by hail; when he arose, he would be scorched by fire in conformity to the punishments meted out to wicked men in the netherworld… (Translation, Samuel A. Berman, with my emendations) The miraculous nature of the Eser Makkot represented the perfect vehicle for teaching the greatness of Hashem. The Ramban (Nachmanides, 1194-1270) gives powerful voice to this idea in his Commentary on the Torah, Sefer Shemot 13:16: Now when G-d is pleased to bring about a change in the customary and natural order of the world for the sake of a people or an individual [that is, a miracle], then the voidance of all these [false beliefs] becomes clear to all people, since a wondrous miracle shows that the world has a G-d Who created it, and Who knows and supervises it, and Who has the power to change it…This is why Scripture says in connection with the wonders [in Egypt]: “in order that you know that I am Hashem in the midst of the earth” (Sefer Shemot 8:18), which teaches us the principle of providence (hashgacha), that is, that G-d has not abandoned the world to chance, as they [the heretics] would have it; “in order that you know that the earth is Hashem’s” (9:29), which informs us of the principle of creation, for everything is His since He created all out of nothing; “in order that you know that there is none like Me in the entire earth” (9:14), which indicates His might, that is, that He rules over everything and that there is nothing to withhold Him. The Egyptians either denied or doubted all of these principles, [and the miracles confirmed their truth]. Accordingly, it follows that the great signs and wonders constitute “trustworthy witnesses” (Sefer Yeshayahu 8:2) to the truth of the belief in the existence of the Creator and the truth of the whole Torah. (Translation, Rabbi Dr. Charles B. Chavel, with my emendations) For the Ramban, the Eser Makkot emerge as one of history’s greatest heuristic devices, as they are exemplars of nissim that teach us Hashem created (bara et HaOlam) and runs the world (hashgacha), that “He rules over everything,” and that there is nothing beyond His control. With Hashem’s help and our fervent desire, may these essential principles of emunah (belief) guide our thoughts and actions each and every day. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org. Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon HaKohane, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Gittel Malka bat Moshe, Alexander Leib ben Benyamin Yosef, the Kedoshim of Har Nof, Pittsburgh, and Jersey City, the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, and the health and safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The final three pasukim of Parashat Shemot are difficult to understand, as they seem to portray a disheartened Moshe Rabbeinu complaining to Hashem: So, Moshe returned to Hashem and said, “O L-rd! Lamah haraota l’am hazeh--Why have You harmed this people? Why have You sent me? Since I have come to Pharaoh to speak in Your name, he has harmed this people, and You have not saved Your people.” And Hashem said to Moshe, “A’tah teireh--Now you will see what I will do to Pharaoh, for with a mighty hand he will send them out, and with a mighty hand he will drive them out of his land.” (Sefer Shemot 5:22-23, 6:1, this and all Tanach and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach, with my emendations) In his Commentary on the Torah, Rashi (1040-1105), following Midrash Tanchuma, Parashat Va’era 6, states that Moshe was, indeed, protesting Hashem’s apparent harm to His people: Lamah haraota l’am hazeh? “And if You [Hashem] ask, ‘What is it to you?’ [I answer,] ‘I am complaining that You have sent me.’” He follows this approach, as well, in his gloss on “a’tah teireh,” wherein the Almighty takes Moshe to task for rejecting the manner in which He runs the world: You have questioned My ways [which is] unlike Avraham, to whom I said, “For in Yitzchak will be called your seed” (Sefer Bereishit. 21:12), and afterwards I said to him, “Bring him up there for a burnt offering” (Sefer Bereishit 22:2), yet he did not question Me. Therefore, a’tah teireh--now you will see. What is done to Pharaoh you will see, but not what is done to the kings of the seven nations when I bring them [the children of Israel] into the land [of Israel]. (Based on Talmud Bavli, Sanhedrin 111a and Midrash Shemot Rabbah 5:23) In sum, according to Rashi, although Moshe will bear witness to the Makkot and Yetziat Mitzraim (the Exodus) his question, lamah haraota l’am hazeh, permanently barred his entrance to Eretz Yisrael. A completely different interpretation is presented by Rabbeinu Chananel ben Chushiel (980-1055), a great 11th century North African Torah commentator: For the expression, “lamah haraota l’am hazeh,” is not an expression of complaint and insolence, but, rather, a question that was asked before the Holy One blessed be He: “Why does the middah (action-based characteristic) of tzaddik v’rah lo, v’rasha v’tov lo--the righteous one to whom evil transpires and the evil one who receives that which is good— [exist in the world?] For Moshe saw the Jewish people in the midst of great and powerful servitude coupled with unending misery, while the evil Egyptians, who rejected Hashem’s very existence, he saw in the midst of great success and tranquility… (Cited in Rabbeinu Bahya ben Asher ibn Halawa’s Commentary on the Torah, this, and the following translations my own) For Rabbeinu Chananel, lamah haraota l’am hazeh is not an impudent declaration, but rather a question regarding the existence of tzaddik v’rah lo, v’rasha v’tov lo in the world. He extends his line of reasoning by underscoring Moshe’s concern that Hashem had allowed Pharoah’s evil to stand against the Jewish people: Therefore, when Moshe saw from the day he came to Pharoah as Hashem’s representative, Pharoah made his yoke heavier upon them (the Jewish people) … he asked Hashem, may He be blessed, “Why have You allowed this evil to befall this people, is it not within Your power to save them? Yet You have not saved them!” … So, too, with [the question,] lamah haraota, which we can now understand as meaning, why have You allowed this evil to stand? For I [Moshe] am afraid lest he [Pharoah] will increase his evil [upon Your people]. At this juncture, Rabbeinu Chananel provides a novel elucidation of a’tah teireh that differs markedly from Rashi’s presentation: And this is what a’tah teireh connotes, namely, the success and tranquility that Pharoah [and his nation enjoy] only serves to double the punishment on their punishment, this is why the text states, “what I will do to Pharaoh,” that is, I [Hashem] have already prepared the Makkot for him. Moreover, this is precisely the reason that I [Hashem] have allowed the servitude to become more noisome since the day I sent you, in order to redouble their punishment, and to increase and amplify the Jewish people’s reward when they stand firm and bear these trials and tribulations in love [and devotion to Me]. In Rabbeinu Chananel’s view, Hashem is explaining to Moshe that the ultimate purpose of His actions will be understood the moment He strikes the Egyptians with the 10 Makkot, for then, their punishment will be doubled according to the ever-increasing burdens they placed upon our people. Moreover, our forebears’ reward will expand, in kind, for having borne these trials in love and devotion to the Almighty. May Hashem continue to guard us from all evil. As Dovid HaMelech proclaimed so long ago: Behold the Guardian of Israel will neither slumber nor sleep. Hashem is your Guardian; Hashem is your shadow; [He is] by your right hand. By day, the sun will not smite you, nor will the moon at night. Hashem will guard you from all evil; He will guard your soul. Hashem will guard your going out and your coming in from now and to eternity. (Sefer Tehillim 121:5-8) V'chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org. Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav |

Details

Archives

July 2024

AuthorTalmid of Rabbi Soloveitchik zatzal Categories |

- Blog: Rabbi David Etengoff: Parashat HaShavuah

- Sefer Bereishit 5784&5785

- Sefer Shemot 5784&5785

- Sefer Vayikra 5784&5785

- Sefer Bamidbar 5784 &5785

- Sefer Bereishit 5782&5783

- Sefer Shemot 5782&5783

- Sefer Vayikra 5782&5783

- Sefer Bamidbar 5782&5783

- Sefer Devarim 5782&5783

- Sefer Bereishit 5780& 5781

- Sefer Shemot 5780&5781

- Sefer Vayikra 5780&5781

- Sefer Bamidbar 578&5781

- Sefer Devarim 578&5781

- Sefer Bereishit 5778&5779

- Sefer Shemot 5778&5779

- Sefer Vayikra 5778&5779

- Sefer Bamidbar 5778&5779

- Sefer Devarim 5778&5779

- Sefer Bereishit 5776&5777

- Sefer Bereishit 5774&5775

- Sefer Bereishit 5772&5773

- Sefer Bereishit 5771&5770

- Sefer Shemot 5776&5777

- Sefer Shemot 5774&5775

- Sefer Shemot 5772&5773

- Sefer Shemot 5771&5770

- Sefer Vayikra 5776&5777

- Sefer Vayikra 5774&5775

- Sefer Vayikra 5772&5773

- Sefer Vayikra 5771&5770

- Sefer Bamidbar 5776&5777

- Sefer Bamidbar 5774&5775

- Sefer Bamidbar 5772&5773

- Sefer Bamidbar 5771&5770

- Sefer Devarim 5776&5777

- Sefer Devarim 5774&5775

- Sefer Devarim 5772&5773

- Sefer Devarim 5771&5770

RSS Feed

RSS Feed