Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Shoshana Elka bat Avraham, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Peretz ben Chaim, the Kedoshim of Har Nof and Pittsburgh, and the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, Moshe ben Itta Golda and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The mitzvah of tzedakah — the equitable distribution of financial resources to the vulnerable among us — is one of the focal points of our parasha: If there will be among you a needy person, from one of your brothers in one of your cities, in your land the L-rd your G-d is giving you, you shall not harden your heart, and you shall not close your hand from your needy brother. Rather, you shall open your hand to him... (Sefer Devarim 15:7-8, this and all Bible translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) My rebbe and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal (1903-1993), explains in the name of his paternal grandfather, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik zatzal (1853-1918), that the phrase, “you shall open your hand to him” constitutes the mitzvat aseh, the positive commandment, that obligates an individual to distribute tzedakah to the poor. (Chumash Mesoras HaRav, Sefer Devarim, page 128) As such, the preceding expression, “you shall not harden your heart, and you shall not close your hand from your needy brother,” comprises the mitzvat lo ta’aseh, the prohibition against acting in a miserly manner toward a fellow Jew in need. As the Rambam zatzal (Maimonides, 1135-1204) states: It is a positive commandment to give tzedakah to the poor among the Jewish people, according to what is appropriate for the poor person, if this is within the financial capacity of the donor, as [the text] states: “You shall open your hand to him.” Anyone who sees a poor person asking and turns his eyes away from him and does not give him tzedakah transgresses a negative commandment, as [the text] states: “you shall not harden your heart, and you shall not close your hand from your needy brother.” (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Matnot Aniyim 7:1-2, translation, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger with my emendations) In his Torah commentary Tzror HaMor on our passage, the great Sephardic exegete, Rabbi Avraham Saba zatzal (1440-1508), builds upon these two mitzvot as a platform for developing our middot — ethical characteristics: For what am I and what is my [so-called] strength? For it is surely the case that He [Hashem] is the One Who gives the strength [to people] so that they may perform meritorious acts. This is precisely why the Torah text states: “you shall open your hand to him,” and that you should pay no heed to any hardness of your heart [that would prevent you from fulfilling this commandment]. You absolutely must, therefore, open up your hand [to satisfy the tzedakah needs of your fellow Jew] — just as Hashem opens up His hand [to provide for the needs of all those in want]. (Translations and brackets my own) Herein, Rav Saba teaches us that everything in this world, including our personal powers and abilities, are gifts from the Almighty. Moreover, he emphasizes the notion that when we respond positively to the needs of others, we emulate our Creator’s actions, an idea that is writ large in Ashrei: “You [Hashem] open Your hand and satisfy every living thing [with] its desire.” (Sefer Tehillim 145:16) Thus far, Rav Saba has primarily focused upon the underlying nature of the pota’ach yado — an individual who gives tzedakah. Yet, how are we to understand the kofetz yado — one who is unwilling to give tzedakah to their fellow Jew? We are indeed fortunate that Rav Saba answers this question: Our Sages teach us [Talmud Bavli, Baba Batra 10a] that one who closes his hand and refuses to give [tzedakah] to the poor is like an idol worshipper. [What is the proof for this assertion?] The text states here [in our parasha]: “Beware, lest there be in your heart an unfaithful thought (davar v’liya’al)...and you will begrudge your needy brother and not give him” (15:9), which is preceded by the phrase: “Unfaithful men (b’nai v’liya’al) have gone forth from among you and have led the inhabitants of their city astray, saying, ‘Let us go and worship other gods, which you have not known.’’ (13:14) Just as [the first instance of v’liya’al] refers to idol worship, so, too, [does v’liya’al in reference to one who refuses to give tzedakah] teach us that he is like one who is engaged in idol worship. How exactly is the kofetz yado like an idol worshipper? Rav Sabba provides us with the following trenchant psychological analysis: ...for when such an individual closes his hand and refrains from giving to the poor, he begins to feel that everything belongs to him, and that it is his strength and power — kocho v’otzem yado — that creates his wealth. This feeling grows until he rejects Hashem, who continuously provides him with the ability to develop and maintain his wealth. This, in turn, leads him to repudiate the totality of the Torah; as such, it is as if he is an idol worshipper. In sum, according to Rav Sabba, the pota’ach yado is an individual who is keenly aware that m’ate Hashem hayitah zot —everything is ultimately from the Almighty. Since this is the case, we must recognize that we are the stewards of the prosperity He bestows upon us, and willingly share these funds with others less fortunate than ourselves. In so doing, we emulate the Creator and demonstrate our loyalty to His Torah. In stark contrast, the kofetz yado, by refusing to give tzedakah, is like an idol worshipper who rejects Hashem and His holy Torah. Since he maintains that all the earthly goods he has acquired are the result of his native abilities and ongoing efforts, he comes to believe that leit din v’leit dayan — there is no judgment and no Judge. With Hashem’s help and our fervent desire, may we ever be counted among those who give tzedakah with open hearts and open hands. And may the zechut (merit) of fulfilling this mitzvah help bring the entire Jewish people closer to the presence of the Almighty in our lives. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org using the search criteria Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.

0 Comments

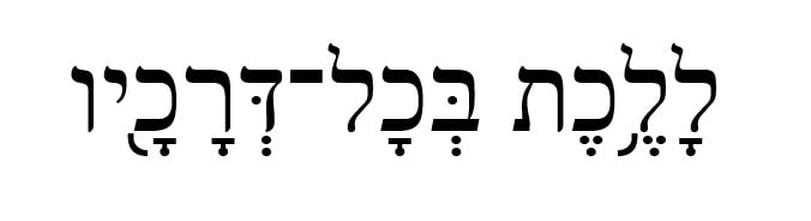

Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Shoshana Elka bat Avraham, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Peretz ben Chaim, the Kedoshim of Har Nof and Pittsburgh, and the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, Moshe ben Itta Golda and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. At the end of our parasha, we find a verse that contains some of the most important theological concepts of Judaism: “For if you keep all these commandments which I command you to do them, to love the L-rd, your G-d, to walk in all His ways, and to cleave to Him.” (Sefer Devarim 11:22, this and all Tanach translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Herein we find the obligations to fulfill Hashem’s mitzvot, love Him, draw close to Him, and “walk in all His ways” — “lalechect bechol d’rachov.” The commandment lalechect bechol d’rachov is found in various textual formulations no less than eight times throughout Sefer Devarim. This repetition is very significant, since it is an accepted principle of Torah exegesis that multiple instances of a phrase or a word demonstrate its singular import. If this is true regarding a word or a phrase, it is certainly the case regarding a mitzvah. The Sifrei on Sefer Devarim helps define the parameters of this mitzvah. In so doing, it helps us understand the classic Jewish emphasis upon sensitivity to others, and our people’s desire to help the vulnerable among us: It is surely the case that just as the Omnipresent One is called, “merciful” so, too, should you be merciful. [Just as] the Holy One blessed be He is called, “gracious” so, too, should you act graciously [toward others]. As the text states: “The L-rd is gracious and compassionate, slow to anger and of great kindness.” (Sefer Tehillim 145:8) … The Omnipresent One is called “the Righteous One, as the text states: “For the L-rd is righteous; He loves [workers of] righteousness, whose faces approve of the straight [way]. (Ibid., 11:7), so, too, should you be righteous. The Omnipresent One is called, “the Kind One,” as the text states: “...I will not let My anger rest upon you, for I am kind, says the L-rd; I will not bear a grudge forever.” (Sefer Yirmiyahu 3:12, with my emendation) So, too, should you be kind [to others]. (Piska 49, translation and brackets my own) Herein, the Sifrei presents a number of Hashem’s attributes of action that are found throughout the Tanach, and urges us to behave in exactly the same manner. This idea is classically known as imitatio Dei (the emulation of the Almighty), and receives its most celebrated presentation in the following Talmudic passage: Just as Hashem clothed the naked [in the case of Adam and Chava] … so, too, should you clothe the naked. Just as Hashem visited the sick [in the case of Avraham after his brit milah] … so, too, should you visit the sick. Just as the Holy One Blessed be He comforted the mourners [in the case of Yitzhak after Avraham’s passing] … so, too, should you comfort the mourners. Just as the Holy One Blessed be He buried the dead [in the case of Moshe] … so, too, should you bury the dead. (Talmud Bavli, Sotah 14a, translation my own) This statement is the basis for a famous halachic ruling of the Rambam (Maimonides, 1135-1204) that defines many of the essentials of Jewish communal life: It is a positive commandment of Rabbinic origin to visit the sick, comfort mourners, to prepare for a funeral, prepare a bride, accompany guests, attend to all the needs of a burial, carry a corpse on one’s shoulders, walk before the bier, mourn, dig a grave, and bury the dead, and also to bring joy to a bride and groom and help them in all their needs. These are deeds of kindness that one carries out with his person that have no limit.” (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Avel 14:1, translation, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger) Closer to our own time, my rebbe and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal (1903-1993), known as “the Rav” by his students and followers, adds an entirely new dimension to our understanding of this commandment: We have an obligation to imitate G-d, and by offering Him appropriate praise, we learn about and appreciate His attributes. The desire to be like Him, to fashion our deeds after a Divine design, is understandable if seen against the background of a relationship based on a passionate love. This emotion expresses itself in an overpowering longing for the complete identification of the lover with the beloved. (Out of the Whirlwind: Essays on Mourning, Suffering and the Human Condition, pages 197-198, underlining my own) The Rav teaches us that we are not merely required to “fashion our deeds after a Divine design.” Far more profoundly, we yearn to do so, because of our overwhelming love of the Master of the Universe, Who is our Yedid Nefesh — the Beloved of our Soul. With Hashem’s eternal kindness as our guide, may we ever strive to fulfill the mitzvah of lalechect bechol d’rachov, and thereby demonstrate our deep and enduring love for Him. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org using the search criteria Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Shoshana Elka bat Avraham, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Peretz ben Chaim, the Kedoshim of Har Nof and Pittsburgh, and the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, Moshe ben Itta Golda and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The halachic imperative to refrain from adding or subtracting from the mitzvot of the Torah is found both in our parasha and in Parashat Re’eh: Do not add to the word (lo tosifu) which I command you, nor diminish from it (v’lo tigra’u), to observe the commandments of the L-rd your G-d which I command you. (Sefer Devarim 4:2, Parashat Va’etchanan, this and all Bible and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Everything I command you that you shall be careful to do it. You shall neither add to it (lo tosaf), nor subtract from it (v’lo tig’ra). (Sefer Devarim 13:1, Parashat Re’eh) Rashi (1040-1105), basing himself upon the words of the Midrash Sifrei to Sefer Devarim (Piska 82), suggests the following interpretation of “lo tosaf” — do not add: You shall neither add to it: [e.g., placing] five chapters in tefillin [instead of four], or [using] five species for the lulav [instead of four], or [reciting] four blessings [instead of three] for the blessing of the kohanim. (13:1) Like the Sifrei, Rashi focuses on the specifics of existing mitzvot. We see this in his above-found explanation of “do not add,” and regarding “nor diminish from it” (4:2), wherein he states: “And so, too, v’lo tigra’u [from it i.e., three instead of four tzitzit or species of plants for the mitzvah of lulav].” Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin, known as the Netziv (1817-1893), takes a different approach to our pasukim (verses). In his Torah commentary, Ha’emek Davar on Sefer Devarim 13:1, he emphasizes the difference in language that obtains between verse 4:2 that is written in the plural — “lo tosifu v’lo tigra’u,” and verse 13:1 that is written in the singular — “lo tosaf v’lo tig’ra.” He suggests that verse 4:2 in the plural form is referring to those individuals who might want to “customize” a particular commandment in a heartfelt effort to actualize their overwhelming love of Hashem. In order to prevent this, the Torah employs the plural form, as if to say to klal Yisrael (the Jewish people), “No matter what you may think or feel, you may not alter any mitzvah of the Torah in order to serve your subjective spiritual needs.” After all, did not Dovid HaMelech (King David) declare: “Torat Hashem temimah — Hashem’s Torah is absolutely perfect.” (Sefer Tehillim 19:8) In contrast, according to the Netziv, the formulation of the prohibition to add or subtract from the Torah that appears in verse 13:1, stated in the singular, contains an entirely new dimension than that found in verse 4:2. It is addressed to Chachmei Yisrael (the Sages of the Jewish people) and, in particular, to the Sanhedrin — the Supreme Court of the Jewish nation: And here, over and above the well-known warning to individuals to refrain from adding to a positive commandment, we find [a new adjuration issued to] the various Sanhedrins [that will exist throughout history]. Herein, they are hereby warned from adding to that which has been accepted within the Torah SheB’al Peh (Oral Law), whether regarding a positive commandment or a negative prohibition...therefore it is written in the singular form, since every nation is referred to in this fashion [that is, as one entity]. This [grammatical construction] is particularly apropos in the case of the Sanhedrin, since it is the source of the entire nation’s halachic rulings... (Translation and brackets my own) In the Netziv’s estimation, bal tosif (you should not add) and bal tigr’a (you should not diminish), therefore, represent a total of two distinct mitzvot that contain two levels of prohibition. The text of Sefer Devarim 4:2 is addressed to individuals among the Jewish people who might seek to alter Torah She’Bichtav (the Written Torah) in order to achieve greater spiritual heights. In contrast, the wording in 13:1 is primarily an admonition to the Sanhedrin to refrain from changing the accepted Massorah (historical transmission) of Torah SheB’al Peh which, like Torah She’Bichtav, was received by Moshe Rabbeinu (our teacher, Moses) on Mount Sinai. With Hashem’s help and our deepest desire, may we strive to fulfill the mitzvot of both Torah She’Bichtav and Torah SheB’al Peh with authenticity and joy, and may this enable us, as individuals and as a nation, to draw ever closer to our Creator. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org using the search criteria Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Shoshana Elka bat Avraham, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Peretz ben Chaim, the Kedoshim of Har Nof and Pittsburgh, and the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, Moshe ben Itta Golda and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Like the Shoah (Holocaust), Tisha b’Av brings us face to face with the problem of evil (theodicy), namely, “If G-d is truly good, why does He allow evil to exist?” In his celebrated essay, “Sacred and Profane, Kodesh and Chol in World Perspective,” my rebbe and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal (1903-1993), known as “the Rav” by his students and followers, asserts that this question remains forever unanswered, even though it: …has tantalized the inquiring mind from time immemorial till the last tragic decade. The acuteness of this problem has grown for the religious person in essence and dimensions. When a minister, rabbi or priest attempt to solve the ancient question of Job’s suffering, through a sermon or lecture, he does not promote religious ends, but on the contrary, does them a disservice. (Gesher, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1966, page 7) He further underscores the nature of the unsolvable problem of theodicy by noting: “The grandeur of religion lies in its mysterium tremendum [great mystery], its magnitude and its ultimate incomprehensibility.” Little wonder, then, that for the Rav, “The beauty of religion with its grandiose vistas reveals itself to men, not in solutions but in problems, not in harmony but in the constant conflict of diversified forces and trends.” If there is ultimately no answer to the question, “If G-d is truly good, why does He allow evil to exist?,” why does Rabbi Elazar HaKalir ask this question in his introductory words to the second kinah (elegy) that we recite on Tisha b’Av morning?: “How (Eikha) could You rush Your wrath, ruining Your loyal people at the hand of Rome?...” As the Rav notes: One could ask what right [do] we have to pose such a question to the Almighty. Normally, the halakha does not permit us to ask this type of question; rather it prescribes that we unquestioningly accept the judgement of G-d. We are guided by the concept that a person is required to bless G-d for bad times, for tragedy and misfortune, just as he blesses G-d for good times (Talmud Bavli, Berakhot 54a). When confronted with tragedy, we do not argue with G-d; rather we say, “Blessed is the true Judge.” We do not understand misfortune… we have no right to expect that we will understand.” (This and the following quotation, The Koren Mesoret HaRav Kinot: With Commentary on the Kinot Based Upon the Teachings of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, page 220) The Rav teaches us that Tish b’Av is unique in that it is an exception to this overarching rule: The case of kinot on Tisha b’Av, however, is an exception to the general rule. We are permitted to ask eikha, because we are following the precedent of Jeremiah the Prophet who posed the question eikha in the book of Lamentations. And Jeremiah posed this question only because he was given a heter, special permission, by G-d Himself...Thus, Rabbi Elazar HaKalir is permitted to address the question eikha to G-d, only because that question was already posed to G-d by Jeremiah in Lamentations. The Rav’s explanation is based upon straightforward logic: Hashem gave the prophet Yirmiyahu a heter (permissibility) to ask “eikha,” and in so doing, we, as his heirs, were given the same right on Tisha b’Av to pose this question. In his posthumous work, The Lord is Righteous in All His Ways: Reflections on the Tish’ah be-Av Kinot, Rav Soloveitchik offers a different, yet complementary, response to his query, “What right [do] we have to pose such a question [eikha] to the Almighty?” The closeness between Ha-Kadosh Baruch Hu [the Holy One blessed be He] and the Jewish people is also strongly reflected in the second kinah we recite on Tish’ah be-Av, “Eikhah atzta ve-appekha” [“How could You rush Your wrath…]. One basic question is asked throughout this kinah, and it is based on one premise, that the relationship between Ha-Kadosh Baruch Hu and Yisrael is the closest that can ever be. It is not that Ha-Kadosh Baruch Hu likes Yisrael, or even loves Yisrael. It is more than that; theirs is a deep, intense relationship that no human being can destroy or even weaken. (This and the following quotation, page 51) At this juncture, the Rav briefly analyzes the essential nature of the relationship that obtains between Ha-Kadosh Baruch Hu and the Jewish people: …the relationship between Ha-Kadosh Baruch Hu and Yisrael is all-embracing, all-inclusive, endless, and without limitation. There is an absolute relationship of love between the Jew and Ha-Kadosh Baruch Hu. Nothing can spoil it, nothing can cool it off, nothing can change it. And if it is between the Jew and Ha-Kadosh Baruch Hu, it is certainly between Keneset Yisrael [the transhistorical corporate entity of the Jewish people] and Ha-Kadosh Baruch Hu. Tisha b’Av is the saddest day of the year. It gives voice to our deepest existential despair and fear as we recount, and re-encounter, the innumerable tragedies that have befallen our people. In the midst of this abject misery, the Rav reminds us that there is always hope for both the individual Jew and Keneset Yisrael ─ yaish tikvah l’Yisrael! ─ for even on this day, all is not lost. Even on this day, when we find ourselves in the throes of national mourning, we can surely rely on the “absolute relationship of love between the Jew and Ha-Kadosh Baruch Hu,” that the Rav describes as “all-embracing, all-inclusive, endless, and without limitation.” These are comforting words indeed ─ words that we surely need to hear. May Hashem, in His boundless love and mercy for the Jewish people, end the Galut (Exile), bring the Mashiach (Messiah) and rebuild the Beit HaMikdash soon and in our days. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org using the search criteria Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

AuthorTalmid of Rabbi Soloveitchik zatzal Categories |

- Blog: Rabbi David Etengoff: Parashat HaShavuah

- Sefer Bereishit 5784&5785

- Sefer Shemot 5784&5785

- Sefer Vayikra 5784&5785

- Sefer Bamidbar 5784 &5785

- Sefer Bereishit 5782&5783

- Sefer Shemot 5782&5783

- Sefer Vayikra 5782&5783

- Sefer Bamidbar 5782&5783

- Sefer Devarim 5782&5783

- Sefer Bereishit 5780& 5781

- Sefer Shemot 5780&5781

- Sefer Vayikra 5780&5781

- Sefer Bamidbar 578&5781

- Sefer Devarim 578&5781

- Sefer Bereishit 5778&5779

- Sefer Shemot 5778&5779

- Sefer Vayikra 5778&5779

- Sefer Bamidbar 5778&5779

- Sefer Devarim 5778&5779

- Sefer Bereishit 5776&5777

- Sefer Bereishit 5774&5775

- Sefer Bereishit 5772&5773

- Sefer Bereishit 5771&5770

- Sefer Shemot 5776&5777

- Sefer Shemot 5774&5775

- Sefer Shemot 5772&5773

- Sefer Shemot 5771&5770

- Sefer Vayikra 5776&5777

- Sefer Vayikra 5774&5775

- Sefer Vayikra 5772&5773

- Sefer Vayikra 5771&5770

- Sefer Bamidbar 5776&5777

- Sefer Bamidbar 5774&5775

- Sefer Bamidbar 5772&5773

- Sefer Bamidbar 5771&5770

- Sefer Devarim 5776&5777

- Sefer Devarim 5774&5775

- Sefer Devarim 5772&5773

- Sefer Devarim 5771&5770

RSS Feed

RSS Feed