Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Shoshana Elka bat Avraham, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Peretz ben Chaim, the Kedoshim of Har Nof and Pittsburgh, and the refuah shlaimah of Yakir Ephraim ben Rachel Devorah, Mordechai ben Miriam Tovah, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Parashat Acharei Mot, known as the parasha of Yom Kippur, focuses upon the manner of observing this Yom Tov in the Mishkan and Beit HaMikdash. One of the many constitutive elements of a Beit HaMikdash-based Yom Kippur is the mitzvah of the Sa’ir Hamish’talai’ach (the Scapegoat) that plays a crucial role in the day’s kapparah (atonement) process: And the male goat upon which the lot “For Azazel” came up, shall be placed while still alive, before the L-rd, to [initiate] atonement upon it, and to send it away to Azazel, [that is, into the desert]...And Aaron shall lean both of his hands [forcefully] upon the live male goat’s head and confess upon it all the willful transgressions of the children of Israel, all their rebellions, and all their unintentional sins, and he shall place them on the male goat’s head, and send it off to the desert with a man, a prepared individual (ish itti). The male goat shall thus carry upon itself all their sins to a desolate land, and he [the ish itti] shall send off the male goat into the desert. (Sefer Vayikra 16: 10, 21-22, these and all Torah and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach, with my emendations, underlining and brackets) The mitzvah of the Sa’ir Hamish’talai’ach, like all Chukim (mitzvot whose rationales currently elude us), contains many mysterious elements that are difficult to understand. One of these is the meaning of the expression, “ish itti,” which may be translated as “a man, a prepared individual.” (See Talmud Bavli, Yoma 66b) The key word in this phrase is “itti,” a noun similar in kind to “tzaddik” (righteous one) or “chacham” (wise individual). From a grammatical perspective, each of these stands on their own without the word “ish” preceding them; therefore, why does the Torah combine ish and itti in our verse? (Analysis based upon the exegesis of our term by the Torah Temimah and the Malbim.) Our question appears to be the driving force behind a Mishnaic period statement found in Talmud Bavli, Yoma 66a-b: “Our Rabbis taught: [Why does the Torah write] ‘ish’ — To teach us that even a non-kohane [that is, any Jewish male, can fulfill the obligations of the itti.]” (Translation and brackets my own) In other words, even though the Sa’ir Hamish’talai’ach is central to effectuating kapparah, and a kohane is necessary throughout the remainder of the atonement process, the itti that brings the Scapegoat to the desert wasteland need not be a kohane. Based upon this approach, itti does not modify ish; rather, the word “itti,” itself, is the essential term. In his article entitled, Sacred and Profane, my rebbe and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal, known as “the Rav” by his students and followers, understands the expression ish itti in a very different manner. He maintains that it is actually a compound noun wherein itti modifies the word ish and, therefore, connotes the idea of the “man of the moment,” since the Hebrew root letters of itti are ayin followed by taf, and spell the word “time.” In the course of his explication of ish itti, the Rav notes that there were significant contrasts between the Kohane Gadol in the Beit HaMikdash, who offered the S’air la’Shem (male goat to Hashem) as part of the kapparah process, and the ish itti who transported the Sa’ir Hamish’talai’ach to the cliffs of the desert wasteland. The former, like his sacrificial offering on behalf of the entire Jewish people, was a “symbol of tradition and eternity, of qualitative time,” whereas the latter, like the animal under his charge that was removed from the holiness of the Beit HaMikdash, was a mere “man of the moment, symbol of temporality and quantitative time.” In his posthumous work, The L-rd is Righteous in All His Ways, the Rav expands upon the differences between quantitative and qualitative time in a profound manner. He states that for Kant and other philosophers: ...a day is nothing. Time is nothing more than a frame of reference, part of a coordinate system. For them, an event is registered in the context of space as well as time. You locate or localize an event, separate it, and study it. That is all. But there is no essence, no substance to time...It is a number, nothing whatsoever but a number. (Page 210, underlining my own) In stark contrast to the philosophic view of time, the Rav asserts that Judaism views this dimension of existence as a precious entity with potential value unto itself: In Yahadut (Judaism), time is something substantive. It has attributes. There is a “good time,” Yom Tov. There is something called yom kadosh, “holy time.” Indeed, the whole concept of kedushat ha-yom (holiness of the day) is reflective of our approach. It indicates that there is substance to the day that can be filled with sanctity. Days and hours are endowed or saturated with holiness...The day is not just a number. It is a creation in and of itself. (Page 211, parentheses and underlining my own) Based upon the Rav’s analyses of the ish itti, Kohane Gadol and Judaism’s concept of time, we are in a much better position to understand a life choice that we face on Yom Kippur and, perhaps, each and every day. The Torah, I believe, is subtly asking us to choose between engaging in the ephemeral and fleeting life of the ish itti, for which time is a mere number, or, with the Kohane Gadol, as our model, living in a manner that sanctifies and endows life with meaning and the potential of unlimited possibilities. The choice is truly within our grasp, for if we choose to keep Hashem’s Torah, our entire people can ultimately serve Him as “a kingdom of Kohanim and a holy nation.” (Sefer Shemot 19:6) With the Almighty’s help and our heartfelt desire, may this be so. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org/ using the search criteria Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.

0 Comments

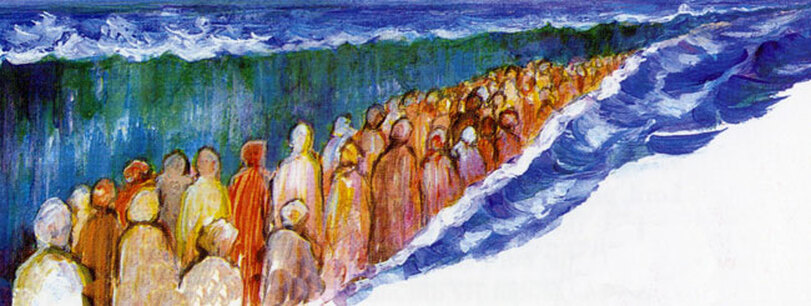

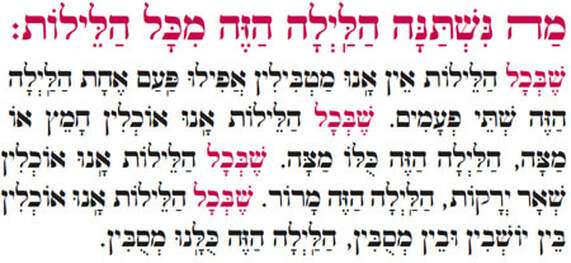

Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Shoshana Elka bat Avraham, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Peretz ben Chaim, the Kedoshim of Har Nof and Pittsburgh, and the refuah shlaimah of Yakir Ephraim ben Rachel Devorah, Mordechai ben Miriam Tovah, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The Yom Tov of Shevi’i shel Pesach (Seventh Day of Pesach) is a continuation of Pesach, rather than a Chag (Festival Day) in its own right. Both the Midrash and Rashi (1040-1105) make it quite clear, however, that this seemingly secondary status in no way diminishes its singular import, since it commemorates an overwhelmingly miraculous moment in our nation’s history, namely, Kriyat Yam Suf – the Splitting of the Sea of Reeds. In turn, this amazing event generated the song of thanksgiving known as the “the Shirat HaYam” ─ “the Song of the Sea:” …On the fifth and the sixth [days after the Jewish people left Egypt], they [the Egyptians] pursued them. On the night preceding the seventh [day], they [the Jewish nation] went down into the sea. In the morning [of the seventh day], they [the Jewish people] recited the Song [of the Sea]. Therefore, we read the Song [from the Torah] on the seventh day, that is the Seventh Day of Passover. (Rashi, Commentary on the Torah, Sefer Shemot 14:5, this and all Bible and Rashi translations with my emendations, The Judaica Press complete Tanach) On a certain level, Rashi’s statement, “they [the Jewish nation] went down into the sea,” conceals more than it reveals, as this matter-of-fact phrase hides the drama that ensued immediately prior to our forebears’descent into the Yam Suf. The best-known Talmudic version of the “story behind the story” is found in Talmud Bavli, Sotah 37a: Rabbi Yehudah responded to him [Rabbi Meir]: What you suggested is not what happened, instead [when the entire nation was standing at the Yam Suf,] this person said, “I am not going down into the water first!” and another responded, “I am not going to go into the water first!” [During this time of endless inaction,] Nachshon ben Aminadav jumped up and became the first one to descend into the waters of the Yam Suf. As the text states: “Ephraim has surrounded me with lies, and the house of Israel with deceit, but Judah [Nachshon ben Aminadav’s tribe] still rules (rad, literally, “has gone down”) with G-d, and with the Holy One He is faithful.” (Sefer Hoshea 12:1, Talmud translation and brackets my own) … The notion that “Nachshon ben Aminadav jumped up and became the first one to descend into the waters of the Yam Suf” is found throughout Midrashic literature. For example, in Bamidbar Rabbah, Parashat Naso 13, we find: “‘Nachshon ben Aminadav of the tribe of Yehudah’ — why was he called ‘Nachshon?’ This is because he was the first to descend l’nachshol sh’b’yam — into the surging waves of the Sea.” Midrash Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer, Chapter 22, takes a different approach than that of Bamidbar Rabbah, and focuses its primary attention on the powerful outcome of Nachshon’s heroic behavior: And Nachshon was the first to jump up and go into the Sea. In so doing, he sanctified His great Name in the eyes of all. [As a result,] under the Tribe of Yehudah’s leadership [that was led by Nachshon], the entire Jewish people followed them and entered the Sea. As the text states: “Judah became His holy nation, Israel His dominion.” — This means under the rulership of the Tribe of Yehudah. (Translation my own) In his work, Netivot Olam (Ahavat Hashem, chapter II), the Maharal of Prague (Rabbi Yehudah Loew ben Bezalel, 1520-1609) notes that Nachshon performed a very special kind of kiddush Hashem (sanctification of G-d's name), in the sense that he did so “b’pharhesia” — before the entire world. In the Maharal’s view, this is the highest form of kiddush Hashem, and is thereby categorized as, “kedushat haShem l’gamrei” — complete and total sanctification of the Divine Name. Clearly, not all of us have the opportunity to undertake Nachshon-like public actions that will lead to a kedushat haShem l’gamrei. None-the-less, each of us can emulate him on our own level. As the Rambam (Maimonides, 1135-1204) teaches us in a celebrated passage in his Mishneh Torah: “Anyone who refrains from committing a sin or performs a mitzvah for no ulterior motive, neither out of fear or dread, nor to seek honor, but for the sake of the Creator, blessed be He...sanctifies G-d’s name.” (Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah V:10, translation, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger) Therefore, with the Almighty’s help and our fervent desire, may each of us dare to be like Nachshon! V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom and Chag Kasher v’Sameach Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org/ using the search criteria Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Shoshana Elka bat Avraham, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Peretz ben Chaim, the Kedoshim of Har Nof and Pittsburgh, and the refuah shlaimah of Yakir Ephraim ben Rachel Devorah, Mordechai ben Miriam Tovah, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. One of the best-known parts of the Haggadah is the section known as “Mah Nishtana,” wherein one or more children at the Seder ask the Four Questions. It is based upon the following Mishnaic statement: Now we pour him [the Seder’s leader] the second cup of wine. At this juncture, the son asks his father [the Four Questions.] If the son lacks the ability to ask (im ain da’at b’ben), his father teaches him, “mah nishtana halailah hazeh mekol halai’lot…” (“how different is this night from all other nights…,” Talmud Bavli, Pesachim 116a, translation and brackets my own) The great Chasidic master, Rabbi Levi Yitzhak of Berdichev (“the Berdichever,” 1740-1810), asks a fascinating question on this Mishnah: “Why does the son ask Mah Nishtana on Passover, and not on the Festival of Succot as well?” (This and the following quotes, Kedushat Levi, Drushim l’Pesach, translations my own) This is a very powerful query, since, like Pesach, Succot has many mitzvot, including sitting in the Succah and the Arba’at Minim (Four Species), that differentiate it from the rest of the year. As such, a child’s interest would surely be piqued, and it, too, should generate the recitation of Mah Nishtana. In order to answer this question, the Berdichever introduces a well-known Talmudic dispute regarding the creation of the world, namely, was the world created in the Spring, in the month of Nissan and Passover, or in the Fall, in the month of Tishrei and Succot? (Talmud Bavli, Rosh Hashanah 10b) In his analysis of this Talmudic debate, the Berdichever submits that Hashem rules the world in two different ways, corresponding to these two seasons of the year. In his view, Tishrei is universal in nature, in the sense that it is the time when Hashem approaches the entire world b’tuvo u’b’chasdo — in His goodness and mercy. In contrast, Nissan is primarily the time when the Almighty relates to the world through the vehicle of Tifferet Yisrael (the glory of the Jewish nation), and exalts Himself through His inseverable connection to Israel, His chosen people. As the Berdichever suggests: “He [Hashem] performs their will [the Jewish people’s] by providing them with all that is positive, in response to that which they request from Him.” Little wonder, then, that Pesach, in the month of Nissan, was the time when we experienced “the miracles and great wonders” of the 10 Plagues and the Splitting of the Sea of Reeds, when we cried out to Him, “O L-rd, save [us]; may the King answer us on the day we call!” (Sefer Tehillim, 20:10, translation, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) At this point, the Berdichever proceeds to answer his initial question, “Why does the son ask the Mah Nishtana on Passover, and not on the Festival of Succot as well?” by introducing the idea of Tzimtzum. This concept maintains that Hashem contracts His Infinite Being in order to communicate with, and be “a part of,” our finite world: This, then is intimated by the [Mishna’s] phrase, “the son asks on Pesach:” For in truth, [the notion] that the Holy One Blessed be He runs the world through [the principle] of Tifferet Yisrael actually means that He contracts Himself [in such a manner that His Divine Presence inheres] in the Jewish people’s worship of Him. He, in turn, has “great pleasure” (ta’a’nug gadol) from this [worship and adoration] and consequently fulfills their will and desire. The Berdichever asserts that when the son asks his father the Four Questions at the Seder, the two of them are engaging in the exact same approach that has always existed between the Jewish people and Hashem: And this model [of the Jewish people requesting their needs from Hashem,] is repeated [at the moment] of the son’s question to his father [at the Seder table]. For, [in truth] the intellectual capacity of the father far exceeds that of the son, and it is only because of the father’s love for his son that he “contracts himself” to provide answers to his son’s [conceptual] difficulties (kushiot). This is the selfsame model that we have already discussed, wherein the [Infinite] Holy One blessed be He “contracts Himself” within [the finite] boundaries of the Jewish people, in order to glorify Himself amongst them (l’hitpaer imahem) by fulfilling their will [and providing for their needs]. The Berdichever has now provided us with a solid understanding as to why the son asks the questions of the Mah Nishtana solely at Pesach. During this Yom Tov, the principle of Tifferet Yisrael is particularly pronounced, for, as we have seen, this is the time when Hashem performed His countless wonders and miracles for us, both in Egypt and at the Sea of Reeds. We beseeched Avinu sh’b’Shamayim (our Father-in-Heaven), and He answered us in an unprecedented manner. What better moment exists, therefore, for children to ask their father to explain the amazing events of the Exodus other than at the Seder itself, for this, too, must surely bring joy to Avinu sh’b’Shamayim. Shabbat Shalom and Chag Kasher v’Sameach Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org/ using the search criteria Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Shoshana Elka bat Avraham, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Peretz ben Chaim, the Kedoshim of Har Nof and Pittsburgh, and the refuah shlaimah of Yakir Ephraim ben Rachel Devorah, Mordechai ben Miriam Tovah, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Our natural inclination at this time of the year is to focus upon the phrase, zacher l’yetziat mitzraim ─ a reminder of the Exodus from Egypt. After all, one of the major mitzvot of Pesach evening is none other than l’saper b’yetziat mitzraim ─ to tell the story of the departure from Egypt. While this is surely a key element of our thoughts during the course of the Seder, the Torah also reminds us, no less than five times, “And you shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt...” (Sefer Devarim 5:15, 15:15, 16:12, 24:18 and 24:22, this and all Bible translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) In sum, while we are certainly obligated to focus upon our joyous march to freedom on the night of Pesach, we are equally mandated to remember our 210-year ordeal of backbreaking servitude and abject misery at the hands of our heartless Egyptian taskmasters. Two of the five instances wherein the Torah enjoins us to “remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt...” explicitly discuss our responsibility to treat the stranger, orphan and widow in an equitable and righteous manner: You shall not pervert the judgment of a stranger or an orphan, and you shall not take a widow's garment as security [for a loan]. You shall remember that you were a slave in Egypt, and the L-rd, your G-d, redeemed you from there; therefore, I command you to do this thing. (Sefer Devarim 24:17-18) When you beat your olive tree, you shall not pick all its fruit after you; it shall be [left] for the stranger, the orphan and the widow. When you pick the grapes of your vineyard, you shall not glean after you: it shall be [left] for the stranger, the orphan and the widow. You shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt: therefore, I command you to do this thing. (24:20-22 with my emendations) These verses urge us to guard the rights and privileges of the most vulnerable members of Jewish society by reminding us, in no uncertain terms, that our entire nation was once completely vulnerable, subject to the diabolical control of Pharaoh and his vicious henchmen. As such, as a people and as individuals, we must build upon the historical consciousness of our Egyptian servitude and be acutely sensitive to the needs of those who require our assistance to live dignified and meaningful lives. In other words, the Torah is commanding us to practice the highest standards of social justice. The Rambam (Maimonides, 1135-1204) codifies our moral and halachic imperative to actively provide for the needs of those most at risk. In the context of a famous halacha regarding the mitzvah of simchat Yom Tov (rejoicing during the Yom Tov meal), he states: When a person eats and drinks [in celebration of a holiday], he is obligated to feed converts, orphans, widows, and others who are destitute and poor. In contrast, a person who locks the gates of his courtyard and eats and drinks with his children and his wife, without feeding the poor and the embittered, is [not indulging in] rejoicing associated with a mitzvah, but rather the rejoicing of his belly. (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Yom Tov 6:18, translation, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger with my emendations) The Rambam is teaching us a profound life lesson that goes far beyond the purview of a specific Yom Tov-based halacha, namely, kol yisrael arevim zeh bazeh — every Jew is personally responsible for the welfare of every other Jew, and no one should ever be left behind. Little wonder, then, that in the opening words of the haggadah we declare as one: This is the bread of affliction that our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt. All those who are hungry, let them enter and eat. All who are in need, let them come celebrate the Passover. Now we are here. Next year in the land of Israel. This year we are enslaved. Next year may we be free. (http://www.mazoncanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/2015-Passover-Resource.pdf) B’shanah haba b’yerushalayim habanuyah! — may we all join as one united people in the rebuilt Beit HaMikdash soon, and in our days. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom and Chag Kasher v’Sameach Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org/ using the search criteria Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

AuthorTalmid of Rabbi Soloveitchik zatzal Categories |

- Blog: Rabbi David Etengoff: Parashat HaShavuah

- Sefer Bereishit 5784&5785

- Sefer Shemot 5784&5785

- Sefer Vayikra 5784&5785

- Sefer Bamidbar 5784 &5785

- Sefer Bereishit 5782&5783

- Sefer Shemot 5782&5783

- Sefer Vayikra 5782&5783

- Sefer Bamidbar 5782&5783

- Sefer Devarim 5782&5783

- Sefer Bereishit 5780& 5781

- Sefer Shemot 5780&5781

- Sefer Vayikra 5780&5781

- Sefer Bamidbar 578&5781

- Sefer Devarim 578&5781

- Sefer Bereishit 5778&5779

- Sefer Shemot 5778&5779

- Sefer Vayikra 5778&5779

- Sefer Bamidbar 5778&5779

- Sefer Devarim 5778&5779

- Sefer Bereishit 5776&5777

- Sefer Bereishit 5774&5775

- Sefer Bereishit 5772&5773

- Sefer Bereishit 5771&5770

- Sefer Shemot 5776&5777

- Sefer Shemot 5774&5775

- Sefer Shemot 5772&5773

- Sefer Shemot 5771&5770

- Sefer Vayikra 5776&5777

- Sefer Vayikra 5774&5775

- Sefer Vayikra 5772&5773

- Sefer Vayikra 5771&5770

- Sefer Bamidbar 5776&5777

- Sefer Bamidbar 5774&5775

- Sefer Bamidbar 5772&5773

- Sefer Bamidbar 5771&5770

- Sefer Devarim 5776&5777

- Sefer Devarim 5774&5775

- Sefer Devarim 5772&5773

- Sefer Devarim 5771&5770

RSS Feed

RSS Feed