|

Rabbi David Etengoff

Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, HaRav Yosef Shemuel ben HaRav Reuven Aharon, David ben Elazar Yehoshua, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana, Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka and Leah bat Shifra, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The post-Flood world should have been one wherein mankind felt chastened and humbled before the Almighty, having just survived near universal decimation. Moreover, logic would dictate that they should have demonstrated overwhelming hakaret hatov (manifest gratitude) to the Almighty for the mercy He had bestowed upon them. Instead, we are presented with the following disturbing narrative of the Tower of Babel: Now the entire earth was of one language and uniform words. And it came to pass when they traveled from the east, that they found a valley in the land of Shinar and settled there. And they said to one another, “Come, let us make bricks and fire them thoroughly;” so the bricks were to them for stones, and the clay was to them for mortar. And they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make ourselves a name, lest we be scattered [by G-d] upon the face of the entire earth.” (Sefer Bereishit 11:1-4, this and all Tanach and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) At this juncture, “the L-rd descended to see the city and the tower that the sons of man had built.” (11:5) The expression, “the sons of man had built,” is rather peculiar for, in reality, who but men could have built the tower? This question is echoed in Rashi’s (1040-1105) midrashically-inspired comment on our verse: But the sons of whom else [could they have been]? The sons of donkeys and camels? Rather, [this refers to] the sons of the first man (Adam Harishon), who was ungrateful and said (Sefer Bereishit 3: 12): “The woman whom You gave [to be] with me [she gave me of the tree; so I ate”]. These, too, were ungrateful in rebelling against the One Who lavished goodness upon them, and saved them from the Flood. In sum, Rashi views the actions of the Dor Hahaphlagah (Generation of the Tower of Babel) as parallel to the behavior demonstrated by Adam Harishon when asked by Hashem, “Have you eaten from the tree [of knowledge] of which I commanded you not to eat?” (3:11) Rather than taking personal responsibility for violating the one mitzvah entrusted to him, Adam denied culpability and blamed G-d for having given him Chava, and Chava for having given him the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge to eat. The Ba’al HaTurim (Rav Ya’akov ben Asher, 1270-1340) supports this perspective when he notes that Adam’s reaction personifies the pasuk (verse), “He who repays evil for good - evil will not depart from his house.” (Sefer Mishle 17:13) This is a particularly apropos observation, since the concluding Hebrew letters of the phrase, “lo tamish ra’ah” (“evil will not depart”) spell the word “isha” (“woman”) – a homiletic reference to the lack of gratitude to Hashem that Adam so blatantly demonstrated regarding Chava. Both Adam, and the Dor Hahaphlagah, repaid Hashem’s beneficence with ingratitude. Years later, the Dor Hamidbar (the Generation of the Desert) unfortunately repeated this pattern of behavior time and time again. Tosafot in Talmud Bavli, Avodah Zarah 5a, discusses their actions in the following manner: “Therefore, [Moshe] labeled them [the Jewish people as practitioners of] kafui tovah, since they refused [to give thanks to Hashem for all of His beneficence] i.e. they refused to recognize the good that He had done for them in all of theses matters.” The Torah Temimah (Rabbi Baruch Halevi Epstein, 1860-1942) expands upon Tosafot’s gloss and suggests that kafui tovah is far more than a failure to recognize the good that someone else has performed for you; instead, it is a completely conscious rejection of the kindness – as if it never had taken place. The Abarbanel’s (1437-1508) analysis of kafui tovah complements Tosafot’s explication in a deeply psychologically insightful manner: The most evil of all middot (behavioral traits) is kafui tovah. This is the case, since when a person recognizes [and gives voice] to the benefit he has received from another individual, he adds to the strength of the benefactor to [continue to] provide him with overflowing kindness - with a full sense of desire and in complete goodness. When, however, the recipient of manifest kindness consciously withholds the requisite recognition of the good that is his benefactor’s due, he weakens his supporter’s strength and aspiration to demonstrate further kindness to him. (Commentary on the Torah, Sefer Shemot, chapter 29, this and the following translations my own) In order to buttress his exposition of our term, the Abarbanel cites Rav Ammi’s words in Talmud Bavli, Ta’anit 8a: “Rain falls only for the sake of Men of Faith (ba’alei emunah) [i.e. trustworthy people],” as it is said, “Truth will sprout from the earth, and righteousness will look down from heaven.” (Sefer Tehillim 85:12, Talmud translation, The Soncino Talmud) In the Abarbanel’s estimation, ba’alei emunah are the people who practice hakaret hatov. He, therefore, reasons that those who engage in kafui tovah are the same people that our Sages identified as individuals steeped in brazenness and temerity (azut panim) – and the very ones who cause droughts. He maintains that this idea is intimated in the text, “And the rains were withheld, and there has been no latter rain…you refused to be ashamed.” (Sefer Yirmiyahu 3:3) Thus, the Abarbanel opines: Everything proceeds as our Sages said: “During the times that the Jewish people fulfill the will of the Omnipresent [i.e. we practice hakaret hatov and guard the Torah], we add to the power, so to speak, of that which is Above. As the text says, ‘Now, please, let the strength of the Lord be increased, as You spoke…’ (Sefer Bamidbar 14:17) [Conversely,] during the times that the Jewish people fail to fulfill the will of the Almighty [i.e. we are involved with kafui tovah and we do not keep the Torah], we diminish the power, so to speak, of that which is Above. As the text states, ‘You forgot the [Mighty] Rock Who bore you; you forgot the G-d Who delivered you.’” (Sefer Devarim 32:18) Based upon the presentations of Rashi, Tosafot, the Abarbanel and the Torah Temimah, it is clear that kafui tovah is a reprehensible behavioral trait that manifests itself in a knowledgeable and brazen repudiation of the good which either G-d or man has done for us. As such, its remedy must be the polar opposite action, namely, hakaret hatov, wherein we demonstrate heartfelt gratitude to our benefactor through our words and deeds. With Hashem’s help, may we master this middah so that we may fulfill King Solomon’s stirring counsel: “Kindness and truth shall not leave you; bind them upon your neck, inscribe them upon the tablet of your heart; and find favor and good understanding in the sight of G-d and man.” (Sefer Mishle 3:3-4) V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on YUTorah.org using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on “Tefilah: Haskafah and Analysis,” may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.

0 Comments

Rabbi David Etengoff

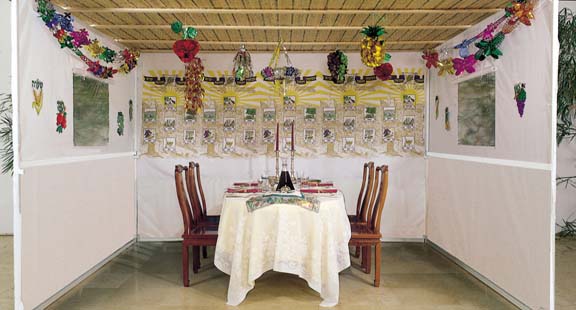

Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, HaRav Yosef Shemuel ben HaRav Reuven Aharon, David ben Elazar Yehoshua, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana, Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka and Leah bat Shifra, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The concluding verses of our parasha portend the impending annihilation of the Generation of the Flood: G-d saw that man’s wickedness on earth was increasing. Every impulse of his innermost thought was evil, all day long. G-d regretted (vayinachem) that He had made man on earth, and He was pained (vayitatzav) to His very core. G-d said, “I will obliterate humanity that I have created from the face of the earth – man, livestock, land animals, and birds of the sky, I regret (nichamti) that I created them.” (Sefer Bereishit 6:5-7, translator, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan zatzal, The Living Torah) This poignant passage is quite remarkable. Herein we are told that Hashem regretted having created humanity to the extent that He was “pained to His very core.” Yet, why was this so? Why did Hashem suffer to the innermost depths of His being? Rashi (1040-1105) explains that He “mourned over the destruction of His handiwork,” i.e. the imminent obliteration of “man, livestock, land animals, and birds of the sky.” In a certain sense, however, Hashem’s reaction is startling. After all, in His omniscience, He knew from the very moment of Creation that man would sin in an egregious fashion and be deserving of extinction. If so, why did G-d create man when He could have spared Himself the abject sorrow of destroying him? Rashi addresses this conundrum in one of his glosses on our verse: A gentile asked Rabbi Joshua ben Korchah, “Do you not admit that the Holy One, blessed be He, foresees the future?” He [Rabbi Joshua] replied to him, “Yes.” He retorted, “But it is written: and ‘He became grieved in His heart!’” He [Rabbi Joshua] replied, “Was a son ever born to you?” “Yes,” he [the gentile] replied. “And what did you do?” he [Rabbi Joshua] asked. He replied, “I rejoiced and made everyone rejoice.” “But did you not know that he was destined to die?” he asked. He [the gentile] replied, “At the time of joy, joy; at the time of mourning, mourning.” He [Rabbi Joshua] said to him, “So is it with the work of the Holy One, blessed be He; even though it was revealed before Him that they would ultimately sin, and He would destroy them, He did not refrain from creating them, for the sake of the righteous people who were destined to arise from them.” (Translation, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Thus, even though Hashem was, by definition, fully cognizant that mankind “would ultimately sin, and He would destroy them,” He nonetheless created man “for the sake of the righteous people who were destined to arise from them.” As such, according to Rashi, Hashem’s personal misery resulting from the deaths of the Generation of the Flood was the necessary price to be paid in order to create a world wherein just and virtuous people would eventually flourish. The Radak (Rav David Kimchi, 1160-1235) offers a very different approach to the terms “vayinachem” and “vayitatzav.” He begins by explaining that “vayinachem” cannot be taken at face value: “This is an instance wherein the Torah employs terminology that is easily understood by the common man; since, in truth, Hashem is not a person and does not regret anything. Moreover, Hashem, may He be blessed and exalted, is ever [perfect and] unchanging The Radak follows a similar approach in his analysis of “vayitatzav”: This, too, is to be understood as a metaphor, since, in truth, Hashem neither engages in joy nor sorrow. In addition, He does not change from one behavior to another… and all of this is nothing other than an allegorical presentation. In other words, just as a person is joyous regarding a matter that is proper and fitting in his eyes, and is sad in regards to something negative in his perception, so, too, is this narrative related about the All-Powerful One may He be blessed – and it is to be understood as discussing Hashem in human terms (al derech ha’avarah). In addition, joy and sadness reside in the heart of a person – therefore, the Torah metaphorically employs the expression, “to His very core (“el libo”) in reference to the All-Powerful One may He be Blessed. (Translations and annotations my own) In sum, the Radak, views the expressions “vayinachem” and “vayitatzav as descriptive phrases that allude to the depths of depravity to which the Generation of the Flood had fallen; they are not, however, to be taken as actual portrayals of Hashem’s behavior. Whether we follow the explication of Rashi or the Radak, it is clear that humankind had reached the nadir of existence in the period before the Flood. As Chazal (our Sages of Blessed Memory) teach us in numerous sources, their actions were so morally reprehensible that they managed to pervert nearly all life forms, with the exception of the fish of the sea, which were beyond their control. In short, without Noach, regarding whom the Torah states, “But Noah found favor in the eyes of Hashem,” (Sefer Bereishit 6:8) mankind and the rest of Creation would have ceased to exist. I believe that we have much to learn from Noach, for it was he, and he alone, who found favor in Hashem’s eyes. His values and behaviors brought nachat ruach (joy to the core) to Hashem, in contrast to those of the rest of mankind who pained our Creator “to His very core.” May we, therefore, emulate Noah by bringing the best of our potential to our lives, as we strive to fulfill the mitzvot of Hashem’s holy Torah. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on YUTorah.org using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on “Tefilah: Haskafah and Analysis,” may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, HaRav Yosef Shemuel ben HaRav Reuven Aharon, David ben Elazar Yehoshua, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana, Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka and Leah bat Shifra, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The public kriah (reading) of King Solomon’s Megillat Kohelet is one of the highlights of Shabbat Chol Hamoed Succot. According to many commentators, it is a précis of its author’s philosophy of life. In particular, the first eight verses of the third chapter of this powerful work have become renowned throughout much of Western culture: Everything has an appointed season (l’kol zeman), and there is a time for every matter (v’ate l’kol chafetz) under the heaven. A time to give birth and a time to die; a time to plant and a time to uproot that which is planted. A time to kill and a time to heal; a time to break and a time to build. A time to weep and a time to laugh; a time of wailing and a time of dancing. A time to cast stones and a time to gather stones; a time to embrace and a time to refrain from embracing. A time to seek and a time to lose; a time to keep and a time to cast away. A time to rend and a time to sew; a time to be silent and a time to speak. A time to love and a time to hate; a time for war and a time for peace. (This, and all Bible and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) A straightforward reading of the verse, “Everything has an appointed season (l’kol zeman), and there is a time for every matter (v’ate l’kol chafetz) under the heaven,” would seem to indicate that it is a preface to the various times that are discussed in the succeeding pasukim (verses). Rashi (1040-1105), however, takes a different approach in his explication of its meaning: “Let not the gatherer of wealth from vanity rejoice, for even though it is in his hand now, the righteous will yet inherit it; only the time has not yet arrived, for everything has an appointed season when it will be.” For Rashi, then, the phrase, “l’kol zeman,” is a highly specific reference to the ultimate transfer of wealth from vain and self-serving people to deservedly righteous individuals. The Maharal of Prague (Rabbi Yehudah Loew ben Bezalel, d. 1609) did not follow Rashi’s approach in viewing these pasukim as referring to the legitimate transfer of wealth. He did agree, however, that our pasuk has its own unique identity and is far more than an introduction to the rest of the perek (chapter). In addition, the Maharal suggests that “l’kol zeman” and “v’ate l’kol chafetz” refer to entirely different subjects, the former emphasizing physical objects and actions, and the latter focusing upon the intellect: Those matters that are [discussed in Midrash Kohelet Rabbah on our verse] are physical in nature, including Adam entering Gan Eden and his exit therefrom, the destruction of the world [at the time of Noach] and its repopulation, and Avraham’s brit milah. [Incontrovertibly,] the body is subject to time. It is fitting, therefore, to use the expression, “l’kol zeman,” when referring to these matters. In contrast, something that is purely intellectual in nature, namely, Kabbalat HaTorah (the Receiving of the Torah), which is divorced in its very essence from all physical matter, is not subject to time [and its multiple strictures]. As such, [when referring to Kabbalat HaTorah, Megillat Kohelet, therefore,] deploys the phrase, “v’ate l’kol chafetz” – because “the now” (“atah” with an ayin, that is etymologically similar to “ate” with an ayin) serves as the bridge between the past and future, yet, in and of itself, is not part of time. (Sefer Tiferet Yisrael, Chapter 25, this, and the following translation and textual notations my own) The Maharal then builds upon this analysis and uses it as an opportunity to elaborate upon the unique nature of Torah: This means that the matter [Torah] is completely of the intellect and, therefore, is not under the control of time. As such, it is permanently in the present (b’atah) – even in regards to when it was given [at Mount Sinai] at that particular time. The Torah was neither given prior to that exact moment or afterwards… for it would not have been proper to have given it prior to leaving Egypt [i.e. before acquiring our physical freedom]… Thus, according to the Maharal, the Torah is permanently in the present (b’atah) and, therefore, above and beyond any concept of time. This idea is quite powerful, and helps us understand why the phrase, “asher anochi metzavecha hayom” (“that I am commanding you this day”), is employed no less than 19 times in Sefer Shemot and Sefer Devarim in reference to the Torah and its mitzvot. As Rashi (1040-1105), basing himself upon the Midrash Sifrei, so beautifully explains, “They (the words of the Torah) should not appear to you as an antiquated edict which no one cares about, but as a new one, which everyone hastens to read.” (Commentary on Sefer Devarim 6:6) We will soon be celebrating Simchat Torah. With Hashem’s help and our heartfelt dedication, may this joyous festival be one wherein we recognize that the Torah is truly above and beyond time, and is commanded to us anew each and every day. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom and Chag Sameach! Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on YUTorah.org using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on “Tefilah: Haskafah and Analysis,” may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, HaRav Yosef Shemuel ben HaRav Reuven Aharon, David ben Elazar Yehoshua, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana, Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka and Leah bat Shifra, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. As Moshe nears the end of his life, he urges our nation to adopt a passionate approach to guarantee the future of Torah, and our consequent sovereignty over the Land of Israel: And he said to them, “Set your hearts to all of the words which I bear witness for you this day, so that you may command your children to observe to do all the words of this Torah. For it is not an empty thing for you, for it is your life, and through this thing, you will lengthen your days upon the land to which you are crossing over the Jordan, to possess it.” (Sefer Devarim 32:46-47, this, and all Bible and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Initially, Moshe teaches us what the Torah is not, “For it is not an empty thing for you,” and only subsequently describes the Torah in positive terms, “for it is your life.” Rashi (1040-1105) elucidates the relationship between these two statements and, in so doing, demonstrates their interconnectivity: For it is not an empty thing for you: “You do not labor over it in vain, for a great reward is contingent upon it, for ‘it is your life’ [that is, the reward is life itself].” In sum, Rashi views life, itself, as the reward for conscientious Torah study, an idea that is found in the well-known phrase from the Evening prayer service: “For they [the words of the Torah] are our life and the length of our days, and about them we will meditate day and night.” (Translation, Artscroll Siddur) A different, yet complementary approach to understanding our passage was offered by the great Spanish philosopher, Rabbi Yosef Albo (1380-1444). He begins his analysis of our pasukim (verses) by noting that Moshe’s words are similar in kind to the type of terminology one finds in the summary portion of any standard contract. Following this, he focuses upon the two types of reward that are promised in our verses: So, too, Moshe Rabbeinu, may peace be upon him, in this instance, wrote these words to remind [the Jewish people] of the two conceptual categories of reward (sh’nay minay ha’s’char hamusagim) that are inherent in the Torah, namely, spiritual and physical reward. In reference to spiritual reward the text states, “for it is your life,” whereas in regards to physical blessing the Torah writes, “and through this thing, you will lengthen your days upon the land.” (Sefer HaIkkarim, Section IV, Chapter 40, this and subsequent translations my own) The expressions “spiritual reward” and “physical reward” are frequently found within Torah literature. They are rarely defined, however, leading to confusion as to their exact meaning. Fortunately, Rav Albo was sensitive to this challenge, and explains the difference between our terms in a convincing manner: In order to differentiate between spiritual and physical rewards, the Torah states, in reference to the former, “For it is not an empty thing for you,” this means to say, do not think that the Torah is something extraneous to you (davar achare zulatchem) – instead, it, in and of itself, is your very life. This refers to the essence of life that remains with a person even after they pass away. This comes to teach us that the knowledge one acquires through the continuous study that is part of the service of Hashem may He be blessed… is, itself, the life giving and sustaining force of the soul after death. This concept is hinted at through the double use of the word “hu” (“it”) [in verse 47]. Spiritual reward, for Rav Albo emerges as “the essence of life that remains with a person, even after they pass away.” As such, Torah knowledge remains with a person’s neshamah (soul) throughout all eternity. At this juncture, Rav Albo demonstrates the manner in which the expression “and through this thing, you will lengthen your days upon the land” references physical reward: This comes to teach us that the concept of physical reward is the direct outcome of fulfilling the Torah and mitzvot. [As valuable as this reward is, however,] it is not the essence of the [highest] reward – instead, it is the natural result of fulfilling the Torah’s [precepts]. By way of example, when the Torah states in reference to the mitzvah of tzedakah (just distribution of money, goods and services to the less fortunate), “for because of this thing the L-rd, your G-d, will bless you in all your work and in all your endeavors,” (Sefer Devarim 15:10) one ought not to think that the underlying reason for performing this mitzvah is to receive multiple blessings; [rather, the service of Hashem is its own reward]. In sum, for Rav Albo, spiritual rewards are the ultimate attainments that enable us to draw closer to Hashem and that remain with our souls - even after death. In contrast, physical rewards are definitionally limited to this world and, therefore, ought not to be pursued on their own account. This notion is reminiscent of the well-known adage in Pirkei Avot, “Do not be as servants who serve their master for the sake of reward. Rather, be as servants who serve their master not for the sake of reward.” (I: 3, this and the following translation, Rabbi Yosef Marcus) As we know, we need both physical and spiritual rewards in order to thrive in this world. This thought, as well, is given powerful voice in Pirkei Avot: “Rabbi Eliezer the son of Azariah would say: ‘If there is no flour, there is no Torah; if there is no Torah, there is no flour.’” (III: 17) Herein, “flour” represents our normative physical needs, whereas “Torah” may be understood both as Torah knowledge per se, and as a metaphor for all spiritually related matters. We have just begun a new year and are on the cusp of celebrating Succot, Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah. May the joy of these festivals continue throughout the coming year, and with Hashem’s help and our renewed devotion, may we fulfill the goals we set for ourselves during the Yamim Noraim, and merit the rewards of Torah. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom and Chag Sameach! Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on YUTorah.org using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on “Tefilah: Haskafah and Analysis,” may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link. 10/2/2016 Parashat Vayelech – Shabbat Shuvah 5777, 2016: Teshuvah and the Process of ChangeRead NowRabbi David Etengoff

Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, HaRav Yosef Shemuel ben HaRav Reuven Aharon, David ben Elazar Yehoshua, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana, Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka and Leah bat Shifra, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Our haftarah contains the famous declaration of the prophet Hoshea, “Return, O Israel, unto the L-rd your G-d (Shuvah Yisrael od Hashem Elokecha), for you have stumbled in your iniquity” (Sefer Hoshea 14:2), and provides this Shabbat with its name, Shabbat Shuvah. Herein, the navi (prophet) urges the entire Jewish people to return Hashem, and once again keep His Torah with heartfelt authenticity. This act of returning is known as “teshuvah,” and serves as the spiritual and conceptual underpinning of the entire period of the Yamim Noraim. In a well-known passage in the Mishneh Torah, Maimonides (the Rambam, 1135-1204) asks, “What is teshuvah?” His answer informs this discussion until our own historical moment: What constitutes Teshuvah? That a sinner should abandon his sins and remove them from his thoughts, resolving in his heart never to commit them again as (Sefer Yeshiyahu 55:7) states: “May the wicked abandon his ways....” Similarly, he must regret the past as (Sefer Yermiyahu 31:18) states: “After I returned, I regretted.” … He must verbally confess and state these matters that he resolved in his heart. (Hilchot Teshuvah II: 2, this and all Hilchot Teshuvah translations, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger) In sum, in the Maimonidean exposition, teshuvah entails four distinct elements: recognition and rejection of the sin (hakarah v’azivah), the determination to never repeat the prohibition (kabbalah al he’atid), remorse for performing the forbidden action (nechamah al he’avar), and the verbal attestation (vidui) of these commitments. Given this understanding as to what teshuvah is, we are prepared to analyze its mitzvah status according to the Rambam, i.e. is it or is it not a precept of the Torah? In his introduction to Hilchot Teshuvah, Maimonides writes, “[This section] contains one positive commandment, that the sinner should return from his sin before Hashem, and should verbally confess (v’yitvadeh).” It appears from this statement that the mitzvah is “the sinner should return from his sin before Hashem,” i.e. teshuvah, and that vidui serves as a handmaiden to this process. The very first halacha following this statement, however, stipulates: If a person transgresses any of the mitzvot of the Torah, whether a positive command or a negative command - whether willingly or inadvertently - when he repents, and returns from his sin, he must confess before G-d, blessed be He as (Sefer Bamidbar 5:6-7) states: “If a man or a woman commit any of the sins of man... they must confess the sin that they committed.” This refers to a verbal confession. This confession is a positive command (vidui zeh mitzvat aseh). Herein, and in seeming opposition to his introductory sentence, the Rambam expressly states that vidui is the mitzvah. As one might suspect, these apparent differences led to two very different approaches among meforshei haRambam (expositors of the Rambam). The Minchat Chinuch (Rabbi Yosef ben Moshe Babad, 1800-1875) and the Avodat HaMelech (Rabbi Menachem Krakowski, 1869-1929) maintained that the Rambam held that there is no mitzvah of teshuvah – only vidui. In contrast, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik (1853-1918), his son, Rav Moshe (1879-1941), and his grandson, Rav Yosef Dov (1903-1993, known as the “Rav”), opined that in Maimonides’ opinion, teshuvah is, in fact, the mitzvah, whereas vidui serves as a constitutive element of the overall teshuvah process. (See Pinchas Peli, ed. of Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik’s Al HaTeshuvah, pages 15-45) The Rav zatzal has a novel understanding of the Rambam’s conceptualization of the mitzvah of teshuvah that is in consonance with his family’s approach to this issue. In his view, the Rambam perceived teshuvah as being similar in kind to the mitzvah of tefillah (prayer), in the sense that both of these commandments, at their core, are experiential and personal, rather than physically demonstrative in nature. Thus he states regarding teshuvah: This is a commandment whose essence is [not exhibited] through various actions and performances; rather, it is a process that, on occasion, takes place over a lifetime. It is a process that begins with remorse, with the sense of guilt, with the recognition by man that he has lost the purpose of his life, with the feeling of loneliness, with [the acknowledgement] of error after error [until his life has become] an empty vacuum… and he continues through this very long process until he achieves his goal – the teshuvah itself. (Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Al HaTeshuvah, Pinchas Peli ed., page 44, this, and all translations, brackets, underlining and parentheses my own) The Rav continues with his analysis of teshuvah, focusing upon its singular ability to alter the very persona of an individual, and the role that vidui plays in this undertaking: Teshuvah is not tied to one particular and conclusive act; instead, it develops and grows in a slow and steady fashion until it brings the person to a metamorphosis. And then, [and only then,] after he changes and becomes a different person, is the act of teshuvah [ready to take place]. And what is the act of teshuvah? One may say that it is vidui. (Pages 44-45) Rav Soloveitchik now expands upon the relationship that obtains between the mitzvah of teshuvah and vidui. His words are nothing less than an intellectual and spiritual tour de force: [When the Rambam writes,] “When he repents, and returns from his sin, he must confess,” he is following his general approach in such matters: In Halacha, and in regards to the mitzvah action [at hand], he presents teshuvah in its objective sense, in its demonstrative sense, therefore, he writes [immediately after our law,] “How does one properly fulfill [the action] of vidui?” In his prefatory statement to Hilchot Teshuvah, however, when he defines the mitzvah, he hints at the inner experience of teshuvah … the convulsions of the soul that bring him [to the state wherein] “the sinner will return from his sin before G-d.” Then, when the teshuvah has grown to its full power, when he undertakes teshuvah [in practice,] “he will confess.” The Rambam, therefore, stresses and states that according to Halacha, “this confession is a positive command,” and it is the action (p’ulah) of teshuvah. The teshuvah, itself, however, is its fulfillment (ki’yumah) and it is an absolute necessity for vidui, for without it, there is no mitzvah of vidui. (Page 45) At this point, the Rav concludes his discussion by proving the similarity of teshuvah to many other mitzvot of the Torah: Teshuvah, in and of itself, therefore, is the fundamental mitzvah, albeit, a spiritually based mitzvah that has no physical aspect. There are many other mitzvot that are similar in kind, such as tefillah, as we have already mentioned, and the mitzvah of “and you shall love your fellow Jew as yourself;” for this, too, is a mitzvah that is inextricably interwoven with a variety of actions, such as kindness and helping one’s fellow Jew, yet the essence of the love itself is a feeling and in the heart. (Page 45) In sum, according to Rav Soloveitchik, teshuvah, though highly subjective, is “the fundamental mitzvah” for the Rambam, rather than vidui. Like tefillah and the commandment to love one’s fellow Jew, which also involve actions, the essence of the mitzvah of teshuvah resides in our hearts and minds. We are on the cusp of Yom Kippur, when we will beseech the Almighty, “S’lach lanu, m’chal lanu, kappear lanu” (“Forgive us, waive our deserved punishments, and remove all traces of our sins.”) We know that the fulfillment of these requests is contingent upon our heartfelt teshuvah, and sincere desire to reconnect with our Creator. With His help, and through our most powerful efforts, may we return unto Him, and bring the following verse to fruition: “For on this day He shall grant you atonement and purify you [from your sins]; before Hashem, you shall be purified from all your sins.” (Sefer Vayikra 16:30) V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom and g’mar v’chatimah tovah. Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on YUTorah.org using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on “Tefilah: Haskafah and Analysis,” may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

AuthorTalmid of Rabbi Soloveitchik zatzal Categories |

- Blog: Rabbi David Etengoff: Parashat HaShavuah

- Sefer Bereishit 5784&5785

- Sefer Shemot 5784&5785

- Sefer Vayikra 5784&5785

- Sefer Bamidbar 5784 &5785

- Sefer Bereishit 5782&5783

- Sefer Shemot 5782&5783

- Sefer Vayikra 5782&5783

- Sefer Bamidbar 5782&5783

- Sefer Devarim 5782&5783

- Sefer Bereishit 5780& 5781

- Sefer Shemot 5780&5781

- Sefer Vayikra 5780&5781

- Sefer Bamidbar 578&5781

- Sefer Devarim 578&5781

- Sefer Bereishit 5778&5779

- Sefer Shemot 5778&5779

- Sefer Vayikra 5778&5779

- Sefer Bamidbar 5778&5779

- Sefer Devarim 5778&5779

- Sefer Bereishit 5776&5777

- Sefer Bereishit 5774&5775

- Sefer Bereishit 5772&5773

- Sefer Bereishit 5771&5770

- Sefer Shemot 5776&5777

- Sefer Shemot 5774&5775

- Sefer Shemot 5772&5773

- Sefer Shemot 5771&5770

- Sefer Vayikra 5776&5777

- Sefer Vayikra 5774&5775

- Sefer Vayikra 5772&5773

- Sefer Vayikra 5771&5770

- Sefer Bamidbar 5776&5777

- Sefer Bamidbar 5774&5775

- Sefer Bamidbar 5772&5773

- Sefer Bamidbar 5771&5770

- Sefer Devarim 5776&5777

- Sefer Devarim 5774&5775

- Sefer Devarim 5772&5773

- Sefer Devarim 5771&5770

RSS Feed

RSS Feed