|

Rabbi David Etengoff

Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, HaRav Yosef Shemuel ben HaRav Reuven Aharon, David ben Elazar Yehoshua, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana and Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Rosh Chodesh is one of the many well-known topics found in this week’s Torah reading: “The L-rd spoke to Moses and to Aaron in the land of Egypt, saying: ‘This month shall be to you (Hachodesh hazeh lachem) the head of the months; to you it shall be the first of the months of the year.’” (Sefer Shemot 12:2, this and all Bible and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) On a certain level, Rosh Chodesh stands apart from other commandments, since it was the first mitzvah given to the Jewish people, as a nation, instead of to the families of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Rashi (1040-1105), basing himself upon a variety of Midrashic sources, gives voice to this idea in one of his glosses on the very first verse of the Torah: In the beginning: Rabbi Isaac said: “It was not necessary to begin the Torah except from ‘This month shall be to you…,’ which is the first commandment that the Jewish people were commanded, [for the main purpose of the Torah is its commandments…’”] Given Rosh Chodesh’s historical and legal significance to our people, it is not at all surprising that rabbinic literature is a treasure trove of halachic analyses and aggadic interpretations regarding its remarkable import. In particular, the figure of Rabbi Elazar ben Arach, the greatest of all the students of Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai (Pirkei Avot II: 9-10), looms large in the list of famous Torah personalities associated with Rosh Chodesh. The following Talmudic narrative highlights the singular significance of this mitzvah: Rabbi Chelbo said: The wine of Perugitha and the water of Diomsith cut off the Ten Tribes from Israel [due to their powerful hedonistic and anti-Torah influences - Rashi]. Rabbi Elazar ben Arach visited those places. He was attracted to them [the wine and the bath waters] and [in consequence,] his learning was uprooted [i.e. he forgot it – Rashi]. When he returned [to the community of scholars], he arose to read the Torah. He wished to read, “Hachodesh hazeh lachem” (“This month shall be to you…”) [instead,] he read “Hacharesh hayah libbam” (“Their hearts were silent”). But the scholars prayed for him, and his learning returned. (Talmud Bavli, Shabbat 147b, translation, The Soncino Talmud with my emendations) The second Bobover Rebbe, HaRav Ben-Zion Halberstam zatzal (1874-1941), in his work, “Kedushat Tzion,” states the following regarding our Talmudic passage: “We must understand the words of our Sages and the quizzical nature as to why Rabbi Elazar ben Arach was called upon to read the specific parasha of ‘Hachodesh hazeh lachem.’” Rav Halberstam’s exploration of the connection between Rabbi Elazar and Rosh Chodesh sheds a good deal of light upon the concept of mitzvah goreret mitzvah (one commandment brings another in its wake, Pirkei Avot 4:2), and the problems associated with mitzvat anashim m’lumdah (the automatic performance of a commandment): The meforshim (commentators) ask, “Does the phrase, ‘mitzvah goreret mitzvah’ really imply that an individual who performs one commandment will henceforth be like an unceasing river [of mitzvot observance], since one commandment brings another in its wake [i.e. ad infinitum] so that the entire rest of his life will be, by definition, mitzvot-infused?” (Kedushat Tzion, Parashat Bo, page 98, this, and the following translations, my own) Rav Halberstam summarizes the commentators’ response to this question in the following fashion: The meforshim address this difficulty by noting that the uniquely valuable reward inherent in the phrase “mitzvah goreret mitzvah” applies solely to a commandment that is performed with deep intention (“b’kavanat halev”) and in its proper manner – then, and only then, does it lead one to perform another mitzvah. If, however, the commandment is performed as a mitzvat anashim m’lumdah, i.e. without proper intention, then it will not lead one to undertake another commandment. One of the clearest expositions of the somewhat elusive phrase, “mitzvat anashim m’lumdah,” was offered by the Malbim (Rabbi Meir Leibush ben Yechiel Michel, 1809-1879). His formulation helps us understand why a commandment performed in this manner fails to engender the performance of another commandment, since the one who acts in this fashion is existentially disconnected from the mitzvah-gesture: There are those who perform the mitzvot solely because this is what they have become accustomed to do since their youth and they are used to performing them. They perform them without any cognitive gesture (kavanah) and without thought – even though they may know that they are commandments from G-d. They, however, do not perform them in any way because Hashem commanded them to do so. Instead, they perform them because this is what they were dictated to do by their teachers and parents. They [the mitzvot] are performed without any understanding and are mere mechanical actions reinforced by past rote behaviors… (Commentary to Sefer Yeshiyahu 29:13, translation and underlining my own). Given the above analysis, Rav Halberstam suggests that Rabbi Elazar ben Arach was frightened after reading “Hacharesh hayah libbam” in place of our pasuk’s phrase, “Hachodesh hazeh lachem.” Based upon his abiding humility, Rabbi Elazar believed his error resulted from having “failed to properly concentrate when fulfilling the commandments on prior occasions,” for if this were not the case, the great mitzvah of Rosh Chodesh - the subject of his Torah reading - should have come to his aid. After all, as the very first mitzvah given to the entire Jewish people, Rosh Chodesh is followed by all the other commandments, and thereby embodies the concept of mitzvah goreret mitzvah. Rabbi Elazar, therefore, concluded that his mitzvot observance must have been on the low level of mitzvat anashim m’lumdah, which resulted in the loss of the reward and protection of mitzvah goreret mitzvah, and made him susceptible to the lure of hedonistic pursuits and consequent loss of his Torah knowledge. According to Rabbi Halberstam, however, Rav Elazar ben Arach’s “colleagues knew full well that, in truth, he had performed prior mitzvot with the requisite intentionality,” and as a result, “prayed for mercy on his behalf and his learning returned.” This poignant episode underscores the great power and holiness of Rosh Chodesh, and its manifest significance in rabbinic thought. May the merit of our heartfelt observance of this mitzvah bring us bountiful blessings from Hashem and hasten the coming of the Mashiach (Messiah) soon and in our days. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on YUTorah.org using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Megillat Esther, may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.

0 Comments

Rabbi David Etengoff

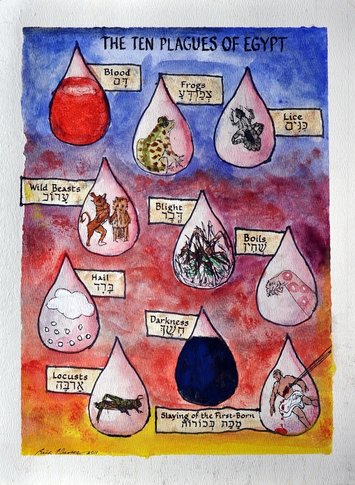

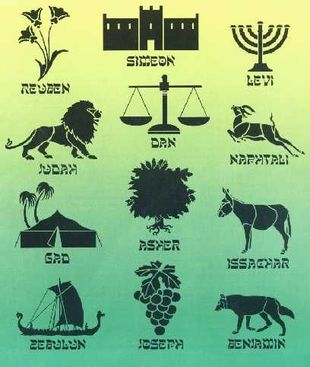

Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, HaRav Yosef Shemuel ben HaRav Reuven Aharon, David ben Elazar Yehoshua, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana and Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Our parasha contains the four instances in Chamisha Chumshei Torah (the Five Books of the Torah) wherein the phrases “l’ma’an teida” (“in order that you should know”) and “ba’avur teida” (“in order that you know”) are deployed: And he [Pharaoh] said, “For tomorrow.” And he [Moses] said, “As you say, in order that you should know that there is none like the L-rd, our G-d.” (Sefer Shemot 8:6, this and all Bible and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) And I will separate on that day the land of Goshen, upon which My people stand, that there will be no mixture of noxious creatures there, in order that you should know that I am the L-rd in the midst of the earth. (8:18) Because this time, I am sending all My plagues into your heart and into your servants and into your people, in order that you know that there is none like Me in the entire earth. (9:14) And Moses said to him [Pharaoh], “When I leave the city, I will spread my hands to the L-rd. The thunder will cease, and there will be no more hail, in order that you should know that the land is the L-rd’s. (9:29) These pasukim (verses) portray Moses in one of two ways, either as Hashem’s faithful messenger to Pharaoh, or as directly responding (i.e., in his own words) to the Egyptian monarch’s challenges to the Almighty. As such, they play a major conceptual role in setting the stage for the Exodus from Egypt. In addition, a close reading of these verses seems to suggest that they have additional holistic import within the wider world of Jewish theology. It is fascinating that this was precisely the approach followed by the Ramban (Nachmanides, 1194-1270) in his Commentary on the Torah, wherein he utilizes the Torah’s presentation of the mitzvah of Tefillin (Sefer Shemot 13:16) to discuss “a general principle (klal) regarding the reason [inherent] in many commandments.” The Ramban opines that with the rise of avodah zarah (idol worship), many of the ikkarei emunah (essential principles of faith) became corrupted or were outright denied: Beginning with the days of Enoch when idol worship came into existence, opinions in the matter of faith fell into error. Some people denied the root of faith by saying that the Universe has always existed; they denied the Eternal[‘s role in Creation], and said; “It is not He [who created the Universe].” Others denied His knowledge of individual matters, and said, “How does G-d know?” and “Is there knowledge in the Most High?” Some admit His knowledge but deny the principle of Divine Providence (hashgacha pratit) and make men as the fishes of the sea, [believing] that G-d does not watch over them, and that there is no punishment or reward for their deeds, for they say “the Eternal has forsaken the world.” (This and the following Ramban translations, http://www.mesora.org/Ramban-Exod-13-16.htm, with my emendations.) The Ramban maintains that the underlying rationale as to why the Torah employs the terms, “l’ma’an teida” and “ba’avur teida,” in reference to the wonders and miracles (moftim) preceding the Exodus, is to prove the veracity of the theological principles of the Creation of the Universe, G-d’s Omnipotence and Divine Providence: This is why the Torah states regarding the wonders [in Egypt]: “in order that you should know that I am the L-rd in the midst of the earth” (8:18) which teaches us the principle of Providence, i.e., that G-d has not abandoned the world to chance, as they [the heretics] would have it. “In order that you should know that the land is the L-rd’s (9:29) which informs us of the principle of Creation, for everything is His since He created all out of nothing. “In order that you know that there is none like Me in the entire earth,” (9:14) which indicates His might (Omnipotence), i.e., that He rules over everything and that there is nothing withheld from Him. In sum, the Ramban asserts, “The Egyptians either denied or doubted all of these principles. Accordingly, it follows that the great signs and wonders constitute faithful witnesses to the truth of the belief in the existence of the Creator and the truth of the entire Torah.” Thus for the Ramban, “l’ma’an teida” and “ba’avur teida” emerge as prologues to some of the most essential theological constructs in Judaism. The Ramban’s analysis and explication of “l’ma’an teida” and “ba’avur teida” is congruent with the notion of the Torah as a book of instruction, since the word “Torah” derives from the infinitive, “l’horot,” which may be translated as “to instruct” or “to teach.” Little wonder, then, that Shlomo HaMelech famously declared, “For I gave you good teaching; forsake not My instruction,” wherein the Hebrew word for “My instruction” is “torahti.” (Sefer Mishle 4:2) When viewed from this perspective, “l’ma’an teida” and “ba’avur teida” serve as introductions to the definitive teachable moments of the Eser Makkot (the Ten Plagues). While the ultimate goal of the Torah is l’horot, I believe one of the major roles of the Jewish people is l’harot (to show) the nations of the world the truth and majesty of Hashem. This concept is exemplified in the second paragraph of the Aleinu: Therefore we put our hope in You, Hashem, our G-d, that we may soon see Your mighty splendor…to perfect the world through the kingdom of the Almighty. Then all humanity will call upon Your Name, to turn all the earth’s wicked toward You. All the world’s inhabitants will recognize and know that to You every knee should bend, every tongue should swear…And it is said: “Hashem will be King over all the world – on that day Hashem will be One and His Name will be One.” (Sefer Zechariah 14:9, Aleinu translations, The Artscroll Siddur with my emendations) With the Almighty’s help, may this time come soon and in our days. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on YUTorah.org using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Megillat Esther, may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, HaRav Yosef Shemuel ben HaRav Reuven Aharon, David ben Elazar Yehoshua, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana and Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The first five pasukim (verses) of our parasha present the names of the leaders of the 12 tribes of Israel that came to Egypt: And these are the names of the sons of Israel who came to Egypt; with Jacob, each man and his household came: Reuben, Simeon, Levi, and Judah. Issachar, Zebulon, and Benjamin. Dan and Naphtali, Gad and Asher. Now all those descended from Jacob were seventy souls, and Joseph was in Egypt. (Sefer Shemot 1:1-5, this and all Bible and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Rashi (1040-1105) asks two midrashically-based questions on the phrase, “and Joseph was in Egypt:” “Did we not know that he [Joseph] was in Egypt?” and “What, then, does this teach us?” The first question is rhetorical in nature, whereas the second is an authentic query. Rav Hezekiah ben Manoach (b. 1250) answers Rashi’s latter question in a straightforward manner that demonstrates a very careful reading of our passage: And Joseph was in Egypt: Regarding the other brothers the Torah employs the words, “habayim mitzraimah” (“those that came to Egypt”). Joseph, however, was not among them, since he was there before they came; nonetheless, he is counted in their assemblage. This, therefore, is the rationale as to why the Torah states, “and Joseph was in Egypt.” (Chizkuni al HaTorah, Sefer Bereishit 1:5, translation my own) Rashi’s response to this question is midrashically-infused: But [this clause comes] to inform you of Joseph’s righteousness. The Joseph who tended his father’s flocks is the selfsame Joseph who was in Egypt and became a king, wherein he maintained his righteousness. (Rashi translation with my emendations) While Rashi stresses Joseph’s continued righteousness in the face of a pleasure-seeking Egyptian society, Midrash Shemot Rabbah focuses upon his unparalleled humility: And Joseph was in Egypt: Even though Joseph merited the kingship, he never lorded this over his brethren and his father’s house. Instead, just as he was initially insignificant in his own eyes when he was a slave in Egypt, so, too, did his self-perception remain after he became the king [of Egypt]. (Translation and brackets my own) In sum, based upon the combined readings of the Midrashim and Rashi, the Joseph who ascended the throne of the most powerful nation in the ancient world remained steadfast in his tziddkut (righteousness) and his anivut (humility). In his Kedushat Levi, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev (1740-1810, known as “the Berdichever”) notes the ostensibly superfluous nature of the word “Egypt” in our phrase “and Joseph was in Egypt.” After all, we have read chapter after chapter in the latter part of Sefer Bereishit wherein this was incontrovertibly the case. The Berdichever, therefore, suggests: One needs to be particularly exact in determining why the text wrote “in Egypt,” when, instead, it should have written, “and Joseph was there.” It appears to me that the proper understanding is that Joseph was in Egypt – i.e. he never changed his name. This was the case even though Pharaoh gave him the new name “Tzafnat Paneach.” (41:45) Nonetheless, he never called himself anything other than Joseph, as is subsequently proven when Pharaoh, himself, declared, “Go to Joseph for he will tell you what to do.” (41:55) The principle that the Jews never changed their names is one of the three reasons why they were ultimately redeemed from Egypt. This, therefore, is the meaning of “and Joseph was in Egypt.” (Translation, underlining and bolding my own) In the Berdichever’s view, therefore, Joseph’s refusal to change his name is reflective of his unwavering refusal to assimilate into the powerful and beguiling Egyptian culture that surrounded him. In his analysis of Joseph’s insistence upon being buried in the Land of Israel, my rebbe and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal (1903-1993), known as “the Rav” by his students and followers, underscores Rav Levi Yitzchak’s conceptualization regarding Joseph’s unwillingness to change his name: He [Joseph] did not ask a favor from his brothers, but he demanded it from the people as a community, as a nation. He wanted to be buried in Canaan like Jacob before him. He wanted to demonstrate the truth that no matter how high an office a Jew might hold in Egypt, no matter how famous and powerful and prominent the Jew is in the general society, his spiritual identity does not change. He belongs to the covenantal community. (This, and the following passages, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Vision and Leadership: Reflections on Joseph and Moses, edited by David Shatz, Joel B. Wolowelsky, and Reuven Ziegler, pages 67-68, underlining my own) At this juncture, the Rav emphasizes that an individual’s thoroughgoing commitment to Judaism does not impede his ability or desire to serve his host country to the very best of his ability. At the same time, however, the nation that he serves must ever grant his right to pursue his Jewish identity: “Of course, his steadfastness as a son of the covenant does not conflict with his political loyalty to the state he serves. But on the other hand, the state itself cannot demand from him that he give up his Jewish identity.” Rav Soloveitchik now proceeds to elaborate upon the enduring trans-historical message that Joseph bequeathed to all Jews living in the pre-Messianic era: We believe we can commit ourselves at a political level to the state or the society in which we live and to the people among whom we live. We can commit ourselves to discharge our duty in the most perfect manner while not sacrificing our Jewish identity. Joseph had shown that. But at the same time that he was very loyal and steadfast as a citizen, his devotion as a citizen did not conflict with his determination to retain his Jewish identity. In a very real sense, the Rav is teaching us that Joseph’s ability to integrate into the highest echelons of Egyptian government and society, while simultaneously maintaining an unswerving loyalty to his Jewish identity, is, in fact, a road map to authentic Jewish living in our time. With the Almighty’s help, may we ever continue to hearken to Joseph’s message and remain strong in our Torah commitment and observance, while striving to contribute as citizens of the countries wherein we reside. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on YUTorah.org using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Megillat Esther, may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link. Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, HaRav Yosef Shemuel ben HaRav Reuven Aharon, David ben Elazar Yehoshua, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana and Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Birkat Ya’akov, the Blessing of Jacob, is the most celebrated narrative of our parasha. It contains Jacob’s hope-filled and prophetically inspired blessing to ten of his sons. In stark contrast, Simeon and Levi receive one of the greatest admonishments in the entire Torah: Simeon and Levi are brothers; stolen instruments are their weapons. Let my soul not enter their counsel; my honor, you shall not join their assembly, for in their wrath they killed a man, and with their will they hamstrung a bull. Cursed be their wrath for it is mighty, and their anger because it is harsh. I will separate them throughout Jacob, and I will scatter them throughout Israel. (Sefer Bereishit 49:5-7, this and all Bible and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press complete Tanach, underlining my own) There are many exegetical challenges in our passage. The first pasuk (verse), in particular, is quite difficult to understand. This is the case, since a straightforward reading of the phrase, “Simeon and Levi are brothers,” suggests that it is superfluous, for after all, the Torah has already taught us regarding Leah: … she conceived again and bore a son, and she said, “Since the L-rd has heard that I am hated, He gave me this one too.” So she named him Simeon. And she conceived again and bore a son, and she said, “Now this time my husband will be attached to me, for I have borne him three sons; therefore, He [Hashem via an angel] named him Levi.” (Sefer Bereishit 29:33-34) Clearly, then, “Simeon and Levi are brothers” cannot be understood in its simple sense; both classic and modern meforshim (commentators) have, therefore, grappled with this problem. Rashi (1040-1105) suggests: “[They were] of one [accord in their] plot against Shechem and against Joseph. [Therefore, the Torah states:] ‘And they said one man to his brother … So now, let us go forth and kill him [Joseph].’” (37:19-20) Rabbi Isaac Karo (1458-1535), the uncle and rebbe of Rabbi Joseph Karo (1488-1575, Shulchan Aruch), focuses upon the juxtaposition of our expression to the phrase “stolen instruments are their weapons,” and interprets “Simeon and Levi are brothers” as referring to their consistent actions as comrades in arms, rather than as a reference to their familial relationship. (Toldot Yitzchak, Sefer Bereishit 49:5-7) The Ramban (Nachmanides, 1194-1270), in his Commentary on the Torah, offers one of the most extended treatments of “Simeon and Levi are brothers” and in so doing, underscores the rationale as to why Jacob declared, “Cursed be their wrath for it is mighty, and their anger because it is harsh:” And in my estimation, the proper explanation of the statement, “Simeon and Levi are brothers,” is that they were thoroughly brothers in the sense that they emulated one another and acted in filial fashion toward each other in both their strategic planning and actions. At this juncture, the Ramban begins his analysis of Jacob’s highly critical perception of Simeon and Levi’s behavior: Moreover, I have already explained (34:13) that Jacob was furious with Simeon and Levi when they killed the men of the city [Shechem] because they acted with gratuitous violence. This was the case, since the men of Shechem [except for Shechem, himself,] did not sin against the brothers in any manner – instead, they entered into a covenant of peace with them and were willingly circumcised. As such, they performed an act of teshuvah (repentance) and thereby returned to Hashem. As a result, the men of Shechem became members of the House of Abraham, and were included in those about whom the Torah states, “the souls that they [Abraham and Sarah] had made in Haran.” (Sefer Bereishit 12:5) The Ramban now suggests an additional, and in some ways, more holistic reason as to why Jacob maintained his furious stance with Simeon and Levi: Another reason why Jacob was incensed was in order to ensure that the people of his time would not think that the matter [of Shechem] was a result of his advice. [If this had been their perception,] there would have been a profanation of the Divine name (chilul Hashem) – i.e. if a prophet such as he would have advised his sons to act as brigands and demonstrate this degree of violence. This, then, is precisely the reason why Jacob avowed, “let my soul not enter their counsel” - it was his declaration that he was not part of their [Simeon and Levi’s] plan which resulted in the treacherous mistreatment of them [the men of Shechem]… (Translations, underlining and brackets my own) The Ramban’s focus upon the avoidance of chilul Hashem as one of the driving factors underscoring Jacob’s wrath against Simeon and Levi is congruent with a crucial passage found in Maimonides’ (Rambam, 1135-1204) Mishneh Torah: In addition, there are deeds which are also included in [the category of] the desecration of [G-d's] name, if performed by a person of great Torah stature who is renowned for his piety - i.e., deeds which, although they are not transgressions, [will cause] people to speak disparagingly of him. This also constitutes the desecration of [G-d's] name… Everything depends on the stature of the sage. [The extent to which] he must be careful with himself and go beyond the measure of the law [depends on the level of his Torah stature.] (Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah, V:11, translation, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger, underlining my own) When viewed in tandem, the analyses of the Rambam and the Ramban enable us to understand Jacob’s fury and contempt for Simeon and Levi’s violent behavior. Jacob, like his father Isaac and grandfather Abraham, was a consummate knight of faith. As such, he passionately sought to guard Hashem’s honor and glory, and strongly opposed anyone, including his own children, who could potentially defame the Almighty’s name in this world. Therefore, he roundly censured Simeon and Levi’s actions in Shechem in his final verbal will and testament. With Hashem’s help, may we, like Ya’akov Avinu (our father Jacob), reject every manner of chilul Hashem. Moreover, as the Rambam writes, may we be counted among those “…who refrain from committing a sin or perform a mitzvah for no ulterior motive, neither out of fear or dread, nor to seek honor, but for the sake of the Creator, blessed be He.” (V:10) In this way, may we may sanctify His great and holy name. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on YUTorah.org using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Megillat Esther, may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, HaRav Yosef Shemuel ben HaRav Reuven Aharon, David ben Elazar Yehoshua, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana and Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The Torah contains countless dramatic moments. One of the most powerful ones appears in this week’s parasha, when Joseph finally reveals himself to his brothers: Now Joseph could not bear (l’hitapake) all those standing beside him, and he called out, “Take everyone away from me!” So no one stood with him when Joseph made himself known to his brothers. And he wept out loud, so the Egyptians heard, and the house of Pharaoh heard. And Joseph said to his brothers, “I am Joseph. Is my father still alive?” but his brothers could not answer him because they were startled by his presence. (Sefer Bereishit 45:1-3, this and all Bible and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) The introductory phrase, “Now Joseph could not bear all those standing beside him,” has captured the attention of many classical Torah meforshim (commentators). Rashi (1040-1105), basing himself upon the Midrash, interprets l’hitapake as “to bear” (“lisbol”), and suggests the following explanation: “He [Joseph] could not bear that Egyptians would stand beside him and hear his brothers being embarrassed when he would make himself known to them.” Onkelos, the First Century CE Aramaic translator/interpreter of the Torah, understands l’hitapake in a different fashion. In his view, our term is the equivalent of “l’itchasana” (Aramaic) or “l’hitchazake” (Hebrew, to strengthen one’s self). Onkelos, therefore, would translate our opening phrase as; “Now Joseph could not strengthen himself in the midst of all those standing beside him.” The Ramban (Nachmanides, 1194-1270) builds upon Onkelos’ interpretation and thereby reveals the “story behind the story”: In my estimation, the correct interpretation is that there were numerous individuals present at that moment from the House of Pharaoh and the Egyptians. At this time, he [Joseph] began to feel remorse regarding Benjamin, since feelings of pity were bestirred within him as a result of Judah’s supplications. Hence, Joseph was unable to strengthen himself to control his emotions before all of them [the courtiers and the Egyptians]. Therefore, he called to his servants, “Remove all non-Jews (“ish nachri”) from before me, for I wish to speak with those who remain (i.e. his brothers). The members of the House of Pharaoh and the Egyptians went out from before him, and when they left, Joseph raised his voice and cried aloud. The Egyptians and the courtiers who departed heard Joseph – for they remained in the outer courtyard. (Translation and underlining my own) According to the Ramban, and in notable contrast to Rashi, Joseph’s point of focus was not the potential embarrassment of his brothers, but rather, himself. In my estimation, an emotional outburst, such as the one that was forming in Joseph’s mind, would have been abhorrent in the eyes of the Egyptians, as it would have been interpreted as a sign of weakness and lack of authentic aristocratic bearing – two potentially powerful strikes against the sitting Viceroy of Egypt. Therefore, if the courtiers had witnessed such an act, it would have called into question Joseph’s continued ability to effectively lead the famine-racked nation. In order to forestall any such interpretation of his behavior, Joseph had all of the Egyptians removed from his presence before revealing his true identity to his brothers. In our own time, Rabbi Moshe Sternbuch shlita expands upon Rashi’s interpretation of our narrative. In so doing, he adds to our understanding of Joseph’s righteousness and his singular dedication to truth and justice. He begins by explaining why it was initially necessary for Joseph to cause his bothers such significant anxiety: “In accordance with the halacha, and until this point, his brothers were obligated to undergo pain and emotional discomfort in order to rectify their sin [of having sold Joseph]. Therefore, Joseph acted in a just and legally defensible manner when he caused them anguish.” At this juncture, Rav Sternbuch emphasizes Joseph’s singular orientation toward the twin values of truth and justice: When, however, they had been sufficiently punished, and the time had arrived to reveal himself to them as [their long-lost brother,] Joseph, even at this moment, did not repudiate the ethical characteristic of pursuing the truth. This was the case even though [the brother’s actions] led him to be brought by force to Egypt and to be imprisoned for 12 years. Nonetheless we do not find that Joseph had any interest whatsoever in seeking revenge against them, instead, he acted toward them in a just and forthright manner – as he had done before [they had sold him]. Rav Sternbuch concludes his presentation by providing a clear rationale as to exactly why Joseph had the Egyptian courtiers removed prior to revealing his identity to his brothers: “… he sought to remove all of the Egyptians from before him so that his brothers would not be embarrassed and suffer distress beyond that which the din (law) had mandated.” (Sefer Ta’am v’ Da’at al Chamisha Chumshei Torah, Parashat Vayigash, page 236, translation and brackets my own) As our Sages teach us, Yosef Hatzadik (Joseph the Righteous) was one of the greatest leaders of the Jewish people. As such, we have much to learn from him regarding the ethical values and practices that should inform our daily behaviors. Like Joseph, we must strive to be righteous, seek justice and ever pursue the truth. By internalizing Joseph’s values and emulating his actions, we will be well on our way to fulfilling King David’s immortal words: “Kindness and truth have met; righteousness and peace have encountered one another. Truth will sprout from the earth, and righteousness will look down from heaven.” (Sefer Tehillim 85:11-12, with my emendations) May this be so, soon and in our days, v’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on YUTorah.org using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Megillat Esther, may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

AuthorTalmid of Rabbi Soloveitchik zatzal Categories |

- Blog: Rabbi David Etengoff: Parashat HaShavuah

- Sefer Bereishit 5784&5785

- Sefer Shemot 5784&5785

- Sefer Vayikra 5784&5785

- Sefer Bamidbar 5784 &5785

- Sefer Bereishit 5782&5783

- Sefer Shemot 5782&5783

- Sefer Vayikra 5782&5783

- Sefer Bamidbar 5782&5783

- Sefer Devarim 5782&5783

- Sefer Bereishit 5780& 5781

- Sefer Shemot 5780&5781

- Sefer Vayikra 5780&5781

- Sefer Bamidbar 578&5781

- Sefer Devarim 578&5781

- Sefer Bereishit 5778&5779

- Sefer Shemot 5778&5779

- Sefer Vayikra 5778&5779

- Sefer Bamidbar 5778&5779

- Sefer Devarim 5778&5779

- Sefer Bereishit 5776&5777

- Sefer Bereishit 5774&5775

- Sefer Bereishit 5772&5773

- Sefer Bereishit 5771&5770

- Sefer Shemot 5776&5777

- Sefer Shemot 5774&5775

- Sefer Shemot 5772&5773

- Sefer Shemot 5771&5770

- Sefer Vayikra 5776&5777

- Sefer Vayikra 5774&5775

- Sefer Vayikra 5772&5773

- Sefer Vayikra 5771&5770

- Sefer Bamidbar 5776&5777

- Sefer Bamidbar 5774&5775

- Sefer Bamidbar 5772&5773

- Sefer Bamidbar 5771&5770

- Sefer Devarim 5776&5777

- Sefer Devarim 5774&5775

- Sefer Devarim 5772&5773

- Sefer Devarim 5771&5770

RSS Feed

RSS Feed