Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon HaKohane, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Gittel Malka bat Moshe, Alexander Leib ben Benyamin Yosef, the Kedoshimof Har Nof, Pittsburgh, and Jersey City, the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, and the health and safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Our parasha contains a phrase that is found in the first bracha of the Shemoneh Esrei: G-d your L-rd is the ultimate Supreme Being and the highest possible Authority. HaA-le great (HaGadol), mighty (HaGibor) and awesome (v’HaNorah), who does not give special consideration or take bribes. (Sefer Devarim 10:17, translation, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan zatzal, The Living Torah, with my emendations) In addition, we find that Ezra HaSofer deploys this expression in his prayer before the Jewish people: “And now, our G-d, HaA-le HaGadol, HaGibor, v’HaNorah, Who keeps the covenant and loving- kindness…” (Sefer NechemiahIX:32, this and the following Bible translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) In his commentary on Talmud Bavli, Berachot 33b (s.v. va’takninahu b’tefilah), Rashi (1040-1105) maintains that Ezra’s prayer is the source of our phrase’s inclusion in the Shemoneh Esrei. His assertion, however, is not universally accepted, since the Sha’agat Aryeh (Rabbi Aryeh Leib ben Asher Gunzberg 1695-1785), among others, maintains that Ezra’s use of this expression was a momentary event, whereas its permanent placement in our liturgy is based on our pasuk. (Turei Even, Talmud Bavli, Megillah 25a, s.v. hashta hachi telata) In either case, the phrase, “HaA-le HaGadol HaGibor v’HaNorah,” has become an integral part of our tefilot. We might think that since we declare, “HaA-le Hagadol HaGibor v’HaNorah,” it should be permissible to add other descriptions of the Almighty during the recitation of the Shmoneh Esrei. In early Talmudic times, an anonymous shaliach tzibbur followed this approach, and quickly found himself under the critical scrutiny of the great Rabbi Chanina bar Chama: A certain [reader] went down in the presence of Rabbi Chanina and said, “O’ G-d, the great (HaGadol), mighty (HaGibor), awesome (v’HaNorah), majestic, powerful, awe-filled, strong, fearless, sure and honored.” He [Rabbi Chanina bar Chama] waited until he had finished, and when he completed [his prayer] he said to him, “Have you concluded all the praise of your Master? Why do we want all this?” (Talmud Bavli 33b, translation, The Soncino Talmud with my emendations) Rabbi Chanina was clearly unimpressed with the shaliach tzibbur’s seven additions. As such, he asked him the same rhetorical question that David HaMelech expresses in Sefer Tehillim, “Who can narrate the mighty deeds of Hashem? [Who] can make heard all His praise?” (106:2) Moreover, Rabbi Chanina teaches us that even our phrase, “HaA-le HaGadol HaGibor v’HaNorah,” would have been prohibited, “had not Moshe Rabbeinu mentioned them in the Torah and had not the Men of the Great Assembly come and inserted them into the order of prayers.” Little wonder, then, that Rabbi Chanina subsequently proclaimed to the would-be creative shaliach tzibbur, “And you say all these and still go on!” The Rambam (Maimonides, 1135-1204) codified these ideas in the following halacha: A person should not be profuse in his mention of adjectives describing G-d, and say: “The great, mighty, awesome, powerful, courageous, and strong G-d,” for it is impossible for man to express the totality of His praises. Instead, one should mention [only] the praises that were mentioned by Moshe, of blessed memory (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot TefilahIX:7, translation, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger) The Rambam’s reasoning as to why one is proscribed from adding new expressions in honor of Hashem in the Shemoneh Esrei is clear, “for it is impossible for man to express the totality of His praises.” Quite simply, finite man is incapable of properly representing the majesty and greatness of the Creator. Therefore, we must limit our words to the exact phrase found in the Torah. We are now ready to analyze the three descriptions of Hashem’s actions in our pasuk. I believe each may be viewed as corresponding to one of the three Avot: That is, Avraham’s destiny is inextricably interwoven with the word, “gadol,”Yitzchak’s to “gibor,” and Ya’akov’s to “norah.” The word gadol, and its verbal variant, appear in reference to Avram/Avraham in Parshiot Lech Lecha and Vayera: And I will make you into a great (gadol) nation, and I will bless you, and I will make your name great (va’agadlah), and [you shall] be a blessing.” (Sefer Bereishit 12:2 with my emendation) And Avraham will become a great (gadol) and powerful nation, and all the nations of the world will be blessed in him. (Sefer Bereishit 18:18) In addition to gadol as a description of Avram/Avraham, there is an amazing midrash that presents him as he who enabled the entire world to recognize the greatness (gedultao, a variant of gadol) of Hashem: And there are those who say that he [Mordechai] was the equivalent to Avraham in his generation. Just like our father, Avraham, allowed himself to be tossed into [Nimrod’s] fiery furnace, and in so doing enabled the people of the earth to return to and recognize the greatness (gedultao) of the Holy One blessed be He, as it is written: “and the souls that they made [that is, Avraham and Sarah converted] in Haran…” (Midrash Esther Rabbah VI:2, translation my own) As such, Avraham is forevermore connected to the expression HaA-le Hagadol. Yitzchak was in many ways the epitome of gevurah (great might), in the manner in which Chazal utilized the term in Pirkei Avot (IV:1): “Who is a hero (gibor)? One who overpowers his desires.” On measure, it was precisely this middah that enabled Yitzchak to submit to the Almighty’s will at the Akeidah. Little wonder, then, that both Kabbalistic and Chasidic literature perceive him as personifying this quality. Ya’akov has a very clear connection to “norah.” This is the case, since he declared, “Mah norah hamakom hazeh!” (“How awesome is this place!” Sefer Bereishit 28:17) after discovering he had inadvertently slept on the makom HaMikdash (the place of the future Beit HaMikdash). Consequently, since that grand moment in time, Ya’akov is associated with the norah aspect of the Almighty. With Hashem’s help, and our fervent desire, may we, as heirs of the Avot, come to acknowledge Him as “HaA-le HaGadol HaGibor v’HaNorah.” V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org. Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav

0 Comments

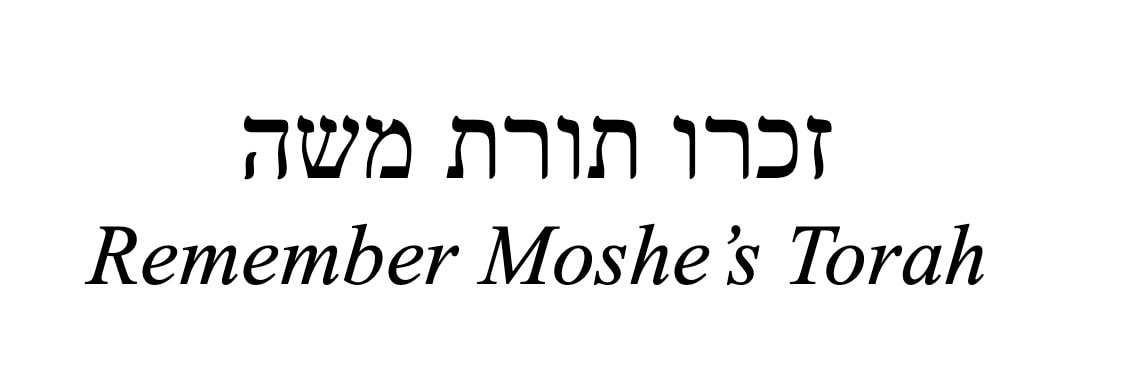

Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon HaKohane, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Gittel Malka bat Moshe, Alexander Leib ben Benyamin Yosef, the Kedoshimof Har Nof, Pittsburgh, and Jersey City, the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, and the health and safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The phrase, “And you shall love Hashem your G-d” appears twice in the Torah; the first instance is in our parasha(Sefer Devarim 6:5), and the second is found in Parashat Eikev (11:1). Our Torah portion’s verse famously states: “And you shall love Hashem, your G-d, with all your heart and with all your soul, and with all your means.” (This and all Bible translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Acknowledging Hashem’s immanence in the world forms the foundation for being able to love Him. The Rambam (Maimonides, 1135-1204), suggests the following approach to recognizing His presence: When a person contemplates His wondrous and great deeds and creations and appreciates His infinite wisdom that surpasses all comparison, he will immediately love, praise, and glorify [Him], yearning with tremendous desire to know [G-d’s] great name, as David stated: “My soul thirsts for Hashem, for the living G-d.” (Sefer Tehillim 42:3, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah II:2, these and all Mishneh Torah translations, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger) In the Rambam’s view, awareness of Hashem stems from a thoroughgoing appreciation of the beauty of the natural world and its infinite complexity. This, in turn, leads to a burning desire to “immediately love, praise, and glorify Him,” and to “know His great name.” Thus far, the Rambam is emphasizing man’s intellectual relationship with the Almighty. As such, he employs the terms “contemplates” (“she’yitbonane”) and “to know” (“lei’da”). Yet, how does one transition from a purely intellectual gesture of love for the Almighty to its practical application? The Rambam addresses this question in his Hilchot Teshuvah: One who serves [G-d] out of love occupies himself in the Torah and the mitzvot and walks in the paths of wisdom for no ulterior motive: not because of fear that evil will occur, nor in order to acquire benefit. Rather, he does what is true because it is true, and ultimately, good will come because of it…G-d commanded us [to seek] this rung [of service] as conveyed by Moshe: “And you shall love Hashem your G-d.” When a man will love G-d in the proper manner, he will immediately perform all of the mitzvot motivated by love. (X:2) Clearly, for the Rambam, love of G-d is expressed in a two-fold fashion: the diligent study of Torah coupled with the fulfillment of the mitzvot—in a manner wherein “he does what is true because it is true.” The Rambam expands upon this idea by asking, “What is the nature of the proper love [of G-d]?” His answer informs Jewish thought until the present moment: That a person should love G-d with a very great and exceeding love until his soul is bound up in the love of G-d. Thus, he will always be obsessed with this love as if he is lovesick. [A lovesick person’s] thoughts are never diverted from the love of that woman. He is always obsessed with her; when he sits down, when he gets up, when he eats and drinks. With an even greater [love], the love for G-d should be [implanted] in the hearts of those who love Him and are obsessed with Him at all times as we are commanded “And you shall love the L-rd, your G-d, with all your heart and with all your soul, and with all your means.” (Hilchot Teshuvah X:3) In the Maimonidean world view, therefore, the love of Hashem is one of powerful passion and obsessive desire, as is metaphorically reflected in King Solomon’s Shir HaShirim (Song of Songs) wherein he states, “Sustain me with flasks of wine, and spread my bed with apples, for I am lovesick.” (2:5) How does one develop such a holistic and deep love for the Creator? Once again, let us turn to the Rambam: “It is a well-known and clear matter that the love of G-d will not become attached within a person’s heart until he becomes obsessed with it at all times as is fitting…” (Hilchot Teshuvah 10:6) Obsession (shugah bah) with the Almighty, therefore, is the key element that enables a person to pursue his love of Him. Little wonder, then, that the Rambam likens the feeling of overwhelming love for one’s beloved to the love one has for the Master of the Universe. At this juncture, the Rambam returns to the connection between man’s knowledge and love of the Almighty: One can only love G-d [as an outgrowth] of the knowledge with which he knows Him. The nature of one’s love depends on the nature of one’s knowledge. A small [amount of knowledge arouses] a lesser love. A greater amount of knowledge arouses a greater love… (Hilchot Teshuvah X:6) On measure, the Rambam is teaching us a crucial lesson regarding the relationship that obtains between G-d and man, namely, that this bond, as in all human relationships, takes ongoing work and effort, and must not be taken for granted. Knowledge of Hashem arouses our love for Him; our engagement in serious Torah study, prayer, and mitzvot observance will enable us to know His ways. As Shlomo HaMelech taught us so long ago: “Know Him in all your ways, and He will direct your paths.” (Sefer Mishle III:6) With Hashem’s help, may this be so, and may our knowledge of Him enable us to fulfill the pasuk, “And you shall love Hashem, your G-d, with all your heart and with all your soul, and with all your means.” V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org. Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon HaKohane, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Gittel Malka bat Moshe, Alexander Leib ben Benyamin Yosef, the Kedoshim of Har Nof, Pittsburgh, and Jersey City, the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, and the health and safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Talmud Bavli, Baba Batra 14b-15b teaches that the Tanach was written by a community of writers: Who wrote the Tanach? Moshe wrote his own book and the portion of Bilam and Iyov. Yehoshua wrote the book, which bears his name, and [the last] eight verses of the Torah. Shmuel wrote the book which bears his name, and Shoftim and Megillat Rut. David wrote Tehillim, including in it the work of the elders, namely, Adam, Melchizedek, Avraham, Moshe, Heman, Yeduthun, Asaph, and the three sons of Korach. Yirmiyahu wrote the book, which bears his name, Sefer Melachim, and Megillat Eicah. Chezkiyahu and his colleagues wrote Yeshayahu, Mishle, Megillat Shir HaShirimand Kohelet. The Men of the Great Assembly wrote Yechezkel, the Twelve Minor Prophets, Daniel and Megillat Esther. Ezra wrote the book that bears his name and the genealogies of Divrei HaYamim up to his own time. (Translation, Soncino Talmud, with my emendations) The phrase, “Moshe wrote his own book,” refers to the Torah. In fact, the Nevi’im and Nehemiah call the Torah, “Torat Moshe,” as we find in Sefer Yehoshua 8:31: As Moshe, the servant of Hashem, commanded the children of Israel, as it is written in the book of the law of Moshe (b’sefer Torat Moshe) an altar of whole stones, upon which no (man) has lifted up any iron. And they offered upon it burnt-offerings to Hashem and sacrificed peace-offerings. And he wrote there upon the stones a copy of Torat Moshe, which he wrote in the presence of the children of Israel. (This, and all Tanach translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach, with my emendations) While the entire Torah is Torat Moshe, Sefer Devarim stands out most prominently as Moshe’s book. The very first pasuk proclaims the personal nature of this final volume of the Torah. Instead of the oft-found phrase, “And Hashem spoke to Moshe saying,” we encounter: “These are the words which Moshe spoke to all Israel on that side of the Jordan in the desert, in the plain opposite the Red Sea, between Paran and Tofel and Lavan and Hazeroth and Di Zahav.” In other words, this sefer, is at one and the same time, divrei Elokim emet and the heartfelt expression of Moshe’s unique love and concern for klal Yisrael. Chazal refer to Sefer Devarim as Mishneh Torah. Tosafot (11th-13th centuries) and the Ramban (1194-1270) explain this term as “repetition of that which was already stated.” In essence, it is primarily a review, or summary, of previously known narrative and halachic passages. In contrast, the Netziv (Rav Naftali Tzvi Yehudah Berlin, 1817-1893), maintains: [The name “Mishneh Torah”] may be properly interpreted and explained as referring to [understanding the Torah] in a holistic fashion—in regard to the specifics and details of its terms and language. Since this is the case, the entire book and its substance is, [in reality,] coming to encourage us to be extensively involved in Torah study so that we will be able to explain the nuances of the text (dikdukei hamikra), as this is [the fundamental nature of] Torah study. Moreover, all of the ethical exhortations (musar), and multiple rebukes of Moshe, were solely for the purpose of [encouraging us] to accept the yoke of Torah study upon ourselves. This idea is based upon the many principles of faith and belief that will be explained within the sefer itself. It is for this reason that it is called by its name “Mishneh Torah,” since it refers to exactitude in Torah study (shinun shel Torah). (HaEmek Davar, Introduction to Sefer Devarim, translation and brackets my own) In sum, according to the Netziv, our Sages coined the name Mishneh Torah to connote Sefer Devarim’s emphasis on meticulous Torah study. Consequently, mishneh, in this instance, means depth-level analysis and knowledge of the Torah, inclusive of its language, laws, and musar. The Netziv cites a fascinating midrash that gives voice to the preeminent position of Sefer Devarim within Rabbinic thought: Rabbi Shimon ben Yochai said: “Sefer Mishneh Torah was the standard (signon) of Yehoshua. [We know this because] at the very moment the Holy One Blessed be He revealed himself to Yehoshua, He found him sitting [and learning] with the Mishneh Torah in his hands.” (Midrash Bereishit Rabbah, Parashat Bereishit, section 6, translation my own) Why was Yehoshua deeply engaged in studying Sefer Devarim rather than one of the other books of the Torah? After all, they, too, incorporate crucial halachot (laws) and ethics. The Netziv’s answer helps us understand the unique nature of Mishneh Torah: “We may learn [from this midrash] that this sefer, in particular, incorporates the entire gamut of moral and ethical principles [that are found throughout the Torah].” In a few days, we will commemorate the heartbreaking events that befell our people on Tisha b’Av. Based on the Netziv’s interpretation of Mishneh Torah, Sefer Devarim emerges as the most appropriate sefer of Chamisha Chumshei Torah to read and study on the Shabbat preceding this day. Beyond question, Tisha b’Av teaches us the necessity to treat our fellow Jews with compassion and understanding—whoever and wherever they may be. This lifelong quest is fraught with innumerable trials. As such, we are blessed that Torat Moshe in general, and Mishneh Torah in particular, provide the roadmap we need to guide us on this challenging journey. Like Yehoshua, may Hashem grant us the wisdom to implement its eternal message as our own. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom and a truly meaningful fast. Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org. Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon HaKohane, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Gittel Malka bat Moshe, Alexander Leib ben Benyamin Yosef, the Kedoshim of Har Nof, Pittsburgh, and Jersey City, the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, and the health and safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The phrase, “aleh hamitzvot (these are the commandments), appears twice in the Torah in the concluding pasukim of Sefer Vayikra and Parashat Masei: These are the commandments (mitzvot) that Hashem commanded Moshe to [tell] the children of Israel on Mount Sinai. (Sefer Vayikra 27:34) These are the commandments (mitzvot) and the ordinances (v’hamishpatim) that Hashem commanded the children of Israel through Moshe in the plains of Moab, by the Jordan at Jericho. (Sefer Bamidbar 36:13, these, and all Bible translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach, with my emendations) The pasukim differ in that the location mentioned in the first pasuk is Har Sinai, whereas the second refers to “the plains of Moab, by the Jordan at Jericho.” Additionally, the first verse only mentions mitzvot, while the second adds mishpatim. In both cases, however, Moshe is tasked to teach the mitzvot to the Jewish people. This concept is alluded to, as well, in the well-known verse, “Torah tzivah lanu Moshe morasha kehillat Ya’akov” (“The Torah that Moshe commanded us is a legacy for the congregation of Ya’akov,” Sefer Devarim 33:4) While the meaning of “aleh hamitzvot” is elusive, the Talmud Yerushalmi offers this analysis: “[This means,] that these [and these alone] are the mitzvot that Moshe instructed us to observe. And so, too, did Moshe teach us: ‘In the future, and from this point forward, no other prophet may originate a new mitzvah for you.’” (Megillah I:V, translation my own) In addition, this principle is found in Midrash Sifrei to Sefer Bamidbar, and four separate times in Talmud Bavli. This repetition signifies its particular import in classical halachic thought. Based upon these sources, the Rambam (Maimonides, 1135-1204), codifies the expression, “no prophet is permitted to create a new matter (that is, mitzvah) from this point forward,” in this manner: It is clear and explicit in the Torah that it [the Torah] is [Hashem’s] mitzvah, remaining forever without change, addition, or diminishment, as [Sefer Devarim 13:1] states: “All these matters which I command to you, you shall be careful to perform. You may not add to it or diminish from it,” and [Sefer Devarim 29:28] states: “What is revealed is for us and our children forever, to carry out all the words of this Torah.” This teaches that we are commanded to fulfill all the Torah's directives forever. It is also said: “It is an everlasting statute for all your generations,” and [Sefer Devarim 30:20] states: “It is not in the heavens.” This teaches that a prophet can no longer add a new precept [to the Torah]. (Mishneh Torah, Sefer Hamada, Hilchot Yesodei HaTorah 9:1, translation, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger, underlining and brackets my own) The Malbim (Rabbi Meir Leibush ben Yechiel Michel, 1809-1879) further explicates the meaning of our phrase, “no prophet is permitted to create a new matter from this point forward.” He opines that “aleh hamitzvot” connotes “these and no others,” and adds, “our teacher Moshe was the sole prophet of the Torah.” As such, “all subsequent prophets had but one purpose—to encourage loyalty to Moshe’ Torah (Torat Moshe).” Thus, by definition, “they could neither add nor subtract [from the Torah].” (Commentary on Sefer Vayikra, section 120, translation my own) The Malbim’s use of the expression, “Torat Moshe,” is similar in kind to a pasuk in Sefer Malachi wherein the navi proclaims, “Remember the Torah of My servant Moshe (Torat Moshe), [inclusive of] the laws and ordinances which I commanded him in Horeb (that is, at Mount Sinai) for all Israel.” (3:22, translation my own) The promise of reward for fulfilling Torat Moshe is found throughout the Torah. One of the most celebrated of these passages appears in the second paragraph of the Shema: And it will be, if you hearken to My commandments that I command you this day to love Hashem, your G-d, to serve Him with all your heart and with all your soul, I will give the rain of your land at its time, the early rain and the latter rain, and you will gather in your grain, your wine, and your oil. And I will give grass in your field for your livestock, and you will eat and be sated. (Sefer Devarim 11:3) This narrative focuses upon the physical rewards that will accrue to our nation if we demonstrate true allegiance to the Almighty. As such the focus is on rain, grain, wine, oil, livestock, and the general satisfaction of our earthly needs. In contrast, Malachi turns our attention to the ultimate spiritual reward, namely, the fulfillment of Judaism’s eschatological vision: “Behold, I will send you Eliyahu HaNavi before the coming of the great and awesome day of Hashem, that he may turn the heart of the fathers back through the children, and the heart of the children back through their fathers…” (23-24) With Hashem’s help, may we ever strive to fulfill His eternal Torat Moshe. Then, may we behold Eliyahu HaNavi, and the coming of Mashiach ben David, soon and in our days. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org. Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon HaKohane, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, Chana bat Shmuel, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Tikvah bat Rivka Perel, Gittel Malka bat Moshe, Alexander Leib ben Benyamin Yosef, the Kedoshim of Har Nof, Pittsburgh, and Jersey City, the refuah shlaimah of Mordechai HaLevi ben Miriam Tovah, and the health and safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Moshe’s multifold accomplishments are legendary. His leadership was extraordinary, the level of nevuah he achieved was different in kind and degree than that of any other prophet who ever lived, and his ability to commune with Hashem is unequaled in the history of our people: “There never arose another prophet amongst the Jewish people like Moshe, to whom Hashem revealed Himself face to face.” (Sefer Devarim 34:10, my translation, as per Onkelos). In his Torah commentary, Torah Temimah, Rabbi Baruch ha-Levi Epstein zatzal (1860-1942) informs us that there was one area, however, wherein Pinchas superseded even Moshe Rabbeinu: “Therefore, let it be said: ‘Behold, I [Hashem] give to him [Pinchas] my Covenant of Peace (brit shalom).’” (Bamidbar25:12) “It is fitting that this atonement [as seen in the words ‘brit shalom’] will continue to bring about expiation forever more.” (Talmud Bavli, Sanhedrin, 82b). At first glance, it is very difficult to understand why Pinchas merited this explicit reward even more than Moshe Rabbeinu, since we find numerous times where, [through Moshe’s efforts,] Hashem “forgot” His anger against the Jewish people, such as in the instances of the Golden Calf and the Spies. (All translations, underlining, brackets and emphasis my own) After raising this fundamental issue, Rav Epstein suggests why Pinchas, and not Moshe, was deserving of the brit shalom: But the matter should, however, be explained in the following manner: We see from this that there was a fundamental difference that obtained between Moshe’s and Pinchas’ ability to remove Hashem’s anger [from upon the Jewish people]. Moshe was able to remove Hashem’s anger for a limited time, yet there remained, so to speak, in Hashem’s heart (mind) a grievance against the Jewish people, just as we find in the instances of the Golden Calf…and the Spies. Peace such as this cannot be called true and absolute peace. In contrast, the removal of Hashem’s anger in Pinchas’ case was a complete and total removal of anger [forevermore]. Therefore, Pinchas merited the just reward [of the brit shalom]. In sum, Pinchas was able to obtain a total and permanent peace between Hashem and His people— devoid of any future recriminations and punishments. This is something that escaped even Moshe Rabbeinu’s grasp. Nonetheless, a crucial question remains: “Why was there such a manifest difference between them?” I believe the following phrase guides us toward an answer: “When he [Pinchas] displayed the anger that I [Hashem] should have displayed.” (Bamidbar 25:11, per Rashi, second gloss on Bamidbar 25:11) In sum, Pinchas acted as Hashem’s messenger in expressing His legitimate anger. He channeled Hashem’s fury in response to the vulgar immorality and idol worship in which many of the men had been engaged. In this sense, Pinchas was a zealot who was completely devoted to Hashem. As such, his total being merged with Hashem’s righteous anger in his desire to execute Hashem’s will. In stark contrast, Moshe Rabbeinu never became angry—neither on a personal level, nor in the service of Hashem, and this is as it should be. Chazal view anger as tantamount to avodah zarah, since in the heat of anger, a person cannot focus upon Hashem, Torah, or mitzvot. Instead, he or she is entirely consumed by the emotion of anger and becomes irrational. Clearly, one of the worst characteristics an authentic leader of klal Yisrael could have is anger. Little wonder, then, that Moshe neither had the personality trait of anger, nor did he become angry—even when it was warranted. Paradoxically, Pinchas was gifted the brit shalom after having brought about total peace between Hashem and klal Yisrael—as a result of the righteous anger he expressed on behalf of the Almighty. In this way, Pinchas served as a protective force and bridged the gaping chasm between Hashem and our people. As spiritually heroic as Pinchas’ actions were, however, it must be stressed that they were permissible solely at that moment in history. Zealotry is simply not, and must never become, an operable concept in the Jewish lexicon of behavior. With Hashem’s help, may we strive to emulate Pinchas’ dedication and devotion to the Holy One blessed be He. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org. Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav |

Details

Archives

July 2024

AuthorTalmid of Rabbi Soloveitchik zatzal Categories |

- Blog: Rabbi David Etengoff: Parashat HaShavuah

- Sefer Bereishit 5784&5785

- Sefer Shemot 5784&5785

- Sefer Vayikra 5784&5785

- Sefer Bamidbar 5784 &5785

- Sefer Bereishit 5782&5783

- Sefer Shemot 5782&5783

- Sefer Vayikra 5782&5783

- Sefer Bamidbar 5782&5783

- Sefer Devarim 5782&5783

- Sefer Bereishit 5780& 5781

- Sefer Shemot 5780&5781

- Sefer Vayikra 5780&5781

- Sefer Bamidbar 578&5781

- Sefer Devarim 578&5781

- Sefer Bereishit 5778&5779

- Sefer Shemot 5778&5779

- Sefer Vayikra 5778&5779

- Sefer Bamidbar 5778&5779

- Sefer Devarim 5778&5779

- Sefer Bereishit 5776&5777

- Sefer Bereishit 5774&5775

- Sefer Bereishit 5772&5773

- Sefer Bereishit 5771&5770

- Sefer Shemot 5776&5777

- Sefer Shemot 5774&5775

- Sefer Shemot 5772&5773

- Sefer Shemot 5771&5770

- Sefer Vayikra 5776&5777

- Sefer Vayikra 5774&5775

- Sefer Vayikra 5772&5773

- Sefer Vayikra 5771&5770

- Sefer Bamidbar 5776&5777

- Sefer Bamidbar 5774&5775

- Sefer Bamidbar 5772&5773

- Sefer Bamidbar 5771&5770

- Sefer Devarim 5776&5777

- Sefer Devarim 5774&5775

- Sefer Devarim 5772&5773

- Sefer Devarim 5771&5770

RSS Feed

RSS Feed