|

Rabbi David Etengoff

Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, Shayna Yehudit bat Avraham Manes and Rivka, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana, Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka, Shoshana Elka bat Etel Dina and Chaya Mindel bat Leah Basha, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The first mention of Lot is found in the midst of the genealogical summations that appear at the end of Parashat Noach: “And Terah lived seventy years, and he begot Abram, Nahor, and Haran. And these are the generations of Terah: Terah begot Abram, Nahor, and Haran, and Haran begot Lot.” (Sefer Bereishit 11:26-27, this and all Bible translations, This Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Lot’s lineage is quite clear; he was the grandson of Terah and the nephew of Avraham Avinu (our father, Abraham). Moreover, Parashat Lech Lecha informs us that he lived a successful pastoral life with Abraham - until the latter deemed it best for them to separate from one another: And also Lot, who went with Abram, had flocks and cattle and tents. And the land did not bear them to dwell together, for their possessions were many, and they could not dwell together. And there was a quarrel between the herdsmen of Abram’s cattle and between the herdsmen of Lot’s cattle… And Abram said to Lot, “Please let there be no quarrel between me and between you and between my herdsmen and between your herdsmen, for we are kinsmen. Is not all the land before you? Please part from me; if [you go] left, I will go right, and if [you go] right, I will go left.” (Sefer Bereishit 13:5-9) Lot followed Abraham’s adjuration and, seemingly because of his vast cattle holdings, “… chose for himself the entire plain of the Jordan.” The outcome of his choice altered the course of Jewish history until today: “Abram dwelt in the land of Canaan, and Lot dwelt in the cities of the plain, and he pitched his tents until Sodom.” (Sefer Bereishit 13:11-12) Rashi (1040-1105), basing himself upon Talmud Bavli, Horiot 10b, presents Rabbi Yochanan’s interpretation as to the underlying reason Lot chose to live in Sodom: “And the Midrash Aggadah interprets it in a negative manner: It was because they [the people of Sodom] were lustful and licentious that Lot [desired and] chose their region for himself.” (13:10, translation and brackets my own) As such, Lot’s departure from Abraham was far more than a change of geographic venue based upon economic need. Instead, his choice represented the tacit repudiation of a major part of the pre-Torah ethics and values that Abraham proclaimed and consistently modelled to the world. Given the above, it is fascinating that our parasha initially portrays Lot in a very positive light, and as a champion of one of Abraham’s most celebrated behaviors, namely, hachnassat orchim (attending to the needs of one’s guests): And the two angels came to Sodom in the evening, and Lot was sitting in the gate of Sodom, and Lot saw and arose toward them, and he prostrated himself on his face to the ground. And he said, “Behold now my lords, please turn to your servant's house and stay overnight and wash your feet, and you shall arise early and go on your way.” And they said, “No, but we will stay overnight in the street.” And he urged them strongly, and they turned in to him, and came into his house, and he made them a feast, and he baked unleavened cakes, and they ate. (Sefer Bereishit 19:1-3) Lot had no idea that the “people” before him were really angels. Since he had grown up in Abraham’s home and was well-versed in the mitzvah of hachnassat orchim and its mandatory nature, he felt a strong urge to help these travelers in need. As Rashi states, “From the house of Abraham he learned to look for wayfarers.” (19:1) In this instance, however, there was a powerful confounding factor at play that surely did not escape Lot’s attention - it was a capital crime in Sodom to extend hospitality to wayfarers! Therefore, why did Lot place his very life in danger for this mitzvah, especially in light of his rejection of other key aspects of Abraham’s value system? The great Chasidic master, Rabbi Shmuel Bornsztain zatzal (1855-1926), known as the “Shem Mishmuel” after the title of his most famous work, focused therein upon this conundrum: One must delve deeply to understand the narrative of Lot placing himself in physical danger (sakkanat nefashot) in order to fulfill the commandment of hachnassat orchim – for this is even above and beyond the practice of normal people - even those that are fitting and proper in all areas of their lives (kesharim). Rashi’s suggestion that “from the house of Abraham he learned to look for wayfarers,” is a necessary, but insufficient rationale, to explain why Lot placed himself in life threatening danger, since the people of Sodom had declared this [hachnassat orchim] to be a capital crime. (Shem Mishmuel, Sefer Bereishit, Parashat Vaera, this and the following translation and brackets my own) Rav Bornsztain helps us understand the “story behind the story” regarding Lot’s exceedingly meritorious behavior. Prior to exploring his analysis, let us remember that Lot was the father of Moab from whom Ruth, the Moabite great-grandmother of King David, descended. Armed with this key information, we are ready to encounter the Shem Mishmuel’s deeply mystical perception of the inner essence of Lot’s neshama (soul), and his behavior with the angels: In addition to our original problem, it is difficult to comprehend, after everything is said and done – and after Lot left Abraham - why all that he had learned from Abraham did not save him [from his wicked and licentious impulses]. According to our understanding (ach l’darcheinu), however, one can say that Lot remained good in his innermost being (b’penimiuto), for after all, the soul of King David continued to remain within him. This, however, was not enough to enable him to improve his actual behavior [in other instances] … After the angels arrived, however, his very essence was aroused, namely, the soul of King David, may his memory be a blessing, and affected even his outward behavior (chitzonioto) until he was willing to put his life in danger for the angels [whom he perceived as human wayfarers]. It is for this reason that he was fitting to be saved [from the annihilation of Sodom and Gomorrah]. Rav Bornsztain’s statement that “Lot remained good in his innermost being (b’penimiuto), for after all, the soul of King David continued to remain within him” is deeply inspiring. It teaches us that no matter how people may appear on the surface, there may be nearly unlimited positive potential within them. This perspective is reminiscent of the words of a gifted young girl that continue to infuse the world with hope and meaning until our own time: It’s really a wonder that I haven’t dropped all my ideals, because they seem so absurd and impossible to carry out. Yet, in spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart. I simply can’t build up my hopes on a foundation consisting of confusion, misery, and death… I can feel the sufferings of millions and yet, if I look up into the heavens, I think that it will all come right, that this cruelty too will end, and that peace and tranquility will return again. (Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, diary entry, Saturday, July 15, 1944, underlining my own) With G-d’s help, may we be zocheh (merit) to witness the time when “iniquity will close its mouth and all wickedness will evaporate like smoke, when You [Hashem] will remove evil’s domination from the earth.” (Translation, The Complete ArtScroll Machzor for Rosh Hashanah, p. 67) May this time come soon and in our days. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org/ using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.

0 Comments

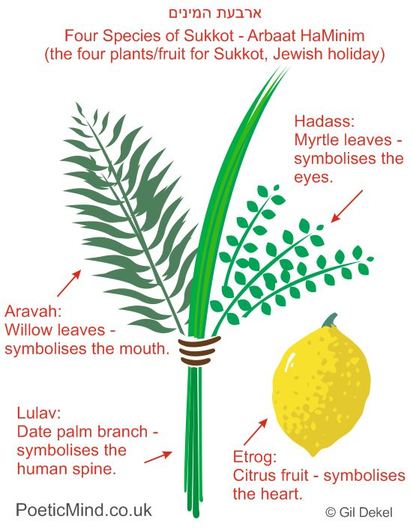

Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, Shayna Yehudit bat Avraham Manes and Rivka, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana, Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka, Shoshana Elka bat Etel Dina and Chaya Mindel bat Leah Basha, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Our parasha contains the sole instances of the specific phrase, “lebrit olam,” (“as an everlasting covenant,”) that appear in Chamisha Chumshei Torah (the Five Books of the Torah): And I will establish My covenant between Me and between you and between your seed after you throughout their generations as an everlasting covenant, to be to you for a G-d and to your seed after you. (17:7) Those born in the house and those purchased for money shall be circumcised, and My covenant shall be in your flesh as an everlasting covenant. (17:13) And G-d said, “Indeed, your wife Sarah will bear you a son, and you shall name him Isaac, and I will establish My covenant with him as an everlasting covenant for his seed after him.” (17:19, this and all Bible translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) A straightforward reading of these pasukim (verses) reveals three separate, yet inextricably interwoven covenants: The unalterable agreement between Hashem, Abraham and all Jews forevermore affirming that the Master of the Universe will always be our G-d, the physical covenant of brit milah (circumcision), and the statement that the covenant of Abraham will continue through his yet-to-be born son, Isaac, and his future offspring. My rebbe and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal (1903-1993), known as “the Rav” by his students and followers, depicted the relationship between these pasukim in the following manner: “With circumcision, another mission was assigned to Abraham: the formation and education of a covenantal community that would be close to G-d and would follow a new way of life, an enigmatic modus existentiae [existential mode of life], a special relationship to G-d.” (Abraham’s Journey: Reflections on the Life of the Founding Patriarch, page 158, brackets my own) What are the constitutive elements of this “covenantal community that would be close to G-d and would follow a new way of life” that Abraham was charged with creating? According to the Rav in his deeply philosophical 1944 work, “U’vikashtem Misham” (“And From There You Shall Seek”), it is comprised of two complementary aspects, Knesset Yisrael and Adat Yisrael: Knesset Yisrael (the Community of Israel) – its definition: the inextricable connection between the first and last generations of prophet and listener, of Torah scholar and student, of the Revelation of G-d’s Divine Presence in the earliest lights of dawn, and the eschatological vision on that day to come. The Community of Israel is also Adat Yisrael (the Congregation of Israel). It incorporates in its innermost being the ancient and true testimony of the myriad visions that have never been obliterated in the depths of the past, the continuity of history, and the unceasing transmission of the Revelation from generation to generation. (Page 66, translation, underlining and parentheses my own) In sum, according to the Rav, the covenantal community that Abraham founded is transhistorical in nature, and definitionally links all Jews to one another for all time. As such, the prophets and their adherents (i.e. the entire Jewish nation), as well as Torah scholars and their students, are eternally bound together by both “the unceasing transmission of the Revelation” that took place on that lonely mountain in the midst of the wasteland of the Sinai Desert, and Judaism’s Messianic vision of enduring peace for all mankind. The Rav has given us a far-reaching theological understanding of the fundamental nature of the covenantal community. We may now well ask: “How did Abraham establish it and ensure its continuation for all time?” I believe the Torah explicitly attests to the secret of his success: “For I [G-d] have known him because he commands his sons and his household after him, that they should keep the way of the L-rd to perform righteousness and justice (la’asot tzedakah u’mishpat), in order that the L-rd bring upon Abraham that which He spoke concerning him.” (Sefer Bereishit 18:19) The extent to which tzedakah u’mishpat have shaped the collective persona of our people is underscored in Talmud Bavli, Yevamot 79a: This nation [Israel] is distinguished by three characteristics: They are merciful (harachmanim), meek (habaishanim) and practitioners of loving-kindness (gomlai chasadim). “Merciful,” as it is written, “and grant you compassion, and be compassionate with you, and multiply you,” (Sefer Devarim 13:18) “Meek,” for it is written, “and in order that His awe shall be upon your faces,” (Sefer Shemot 18:17) “Practitioners of Loving-Kindness,” as it is written, “because he [Abraham] commands his sons and his household after him, that they should keep the way of the L-rd to perform righteousness and justice…” (Sefer Bereishit 18:19, passage translation, The Soncino Talmud with my extensive emendations) Fascinatingly, while we might have thought this passage was merely extra-legal in nature, the Rambam (Maimonides, 1135-1204) teaches us otherwise by codifying it as a normative halacha: “… the distinguishing signs of the holy nation of Israel is that they are meek, merciful, and kind.” (Mishneh Torah, Sefer Kedushah, Hilchot Issurei Biah 19:17, translation, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger) As such, Abraham’s legacy of gemilut chasadim emerges as one of the most prominent characteristics of our nation, and the foundation upon which the covenantal community is based. As the prophet Michah declared: “He has told you, O man, what is good, and what the L-rd demands of you; but to do justice, to love loving-kindness, and to walk humbly with your G-d.” (6:8) With Hashem’s help, may we, as a nation and as individuals, fulfill these stirring words and thereby become links in the great chain of being that began with Abraham and continues for evermore. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org/ using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Megillat Esther may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link. Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, Shayna Yehudit bat Avraham Manes and Rivka, the refuah shlaimah of Devorah bat Chana, Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka, Shoshana Elka bat Etel Dina and Chaya Mindel bat Leah Basha, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. We encounter the following pasuk (verse) toward the end of our parasha, “These are the generations of Terah, Terah was the father of Abraham, Nahor and Haran…” (Sefer Bereishit 11:27) If you were to ask most people to identify Terah, they would probably tell you that he was Abraham’s father and an idol worshipper. This idea is based upon a well-known verse that was popularized by its inclusion in the Passover Haggadah: “And Joshua said to the entire nation, ‘Thus said the L-rd G-d of Israel, your fathers dwelt on the other side of the river from earliest time, Terah, the father of Abraham, and the father of Nahor; and they served other gods.’” (Sefer Yehoshua 24:2, translation, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Many Midrashic passages portray Terah as a highly successful idol manufacturer and one of the great business leaders in Nimrod’s realm. Moreover, Terah’s very name meets with almost universal revulsion based upon the following well-known Midrashic passage in which he voluntarily placed Abraham into Nimrod’s control: He (Terah) took him (Abraham) and gave him over to Nimrod. (Nimrod) said to him: “Let us worship the fire!” (Abraham) said to him: “Should we not then worship water, which extinguishes fire!” (Nimrod) said to him: “Then, let us worship the water!” (Abraham) said to him: “Should we not then worship the clouds, which carry the water?” (Nimrod) said to him: “Then, let us worship the cloud!” (Abraham) said to him: “If so, should we not then worship the wind, which scatters the clouds?” (Nimrod) said to him: “Then, let us worship the wind!” (Abraham) said to him: “Should we not then worship the human, who withstands the wind?” (Nimrod) said to him: “You are merely piling words; we should bow to none other than the fire. I shall therefore cast you in it, and let your G-d to whom you bow come and save you from it!” (Bereishit Rabbah 38:11, ed. Theodor-Albeck, 363-364, translation, http://thetorah.com/why-the-midrash-has-abraham-thrown-into-nimrods-furnace/) In short, from a Jewish perspective, there seems to be little reason to look upon Terah with anything other than total disdain, since his essential values were antithetical to everything Abraham taught the world, namely, dedication to the one true G-d and the singular import of gemilut chasadim (loving-kindness). When we broaden our scope of vision, however, a very different Terah emerges that belies the standard understanding of who we think he was: Rabbi Abba bar Kahana said: “Anyone whose name is mentioned twice in succession in the Tanach is destined to be part of the two worlds [i.e. this world and the world to come]. [As it states,] ‘Noah, Noah,’ ‘Abraham, Abraham,’ ‘Jacob, Jacob,’ (Sefer Bereishit 7:9, 22:12, 46:2), ‘Moses, Moses’ (Sefer Shemot 3:4), ‘Samuel, Samuel’ (Sefer Shmuel I:3:6), ‘Peretz, Peretz’ (Megillat Rut 6:18).” His fellow sages said to him: “Behold [your position must be incorrect, for] does it not say, ‘These are the generations of Terah, Terah was the father of Abraham, Nahor and Haran…’ [And we know, of course, that Terah was an inveterate idol worshipper]!” Rabbi Abba bar Kahana responded to them: “Yes, even he has a portion in the two worlds, for is it not the case that our father, Abraham, was not gathered unto his forefathers until it was made known to him that his father Terah had done teshuvah? As the verse states, ‘And you [Abraham] shall go unto your forefathers in peace…’” (Sefer Bereishit 15:15, Midrash Tanchuma, Sefer Shemot, end of section 18, translation my own) Rashi (1040-1105) briefly alludes to this Midrash when he states, “His [Abraham’s] father worshipped idols and G-d declared to him that he would go unto him [Terah]! Perforce this means that Terah did teshuvah.” (Commentary on the Torah, Sefer Bereishit 15:15, s.v. “el avotecha”) My rebbe and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal (1903-1993), known as “the Rav” by his students and followers, explicates Rashi’s gloss in the following manner: When a father’s antipathy [, as depicted in our earlier Midrash,] toward a son reaches the level of enmity, it is often psychopathological. While enmity toward a stranger is not always a sign of a sick mind or mental aberration, this kind of hostility between father and son is due to a “sick soul” and a personality permeated with hatred… Hazal (our Sages of blessed memory) therefore tell us the story of Terah’s hostility towards Abram, for he saw his destroying everything that he, Terah, had worked to accomplish. Then, suddenly, we hear that Terah repented. (This, and the following quotations of the Rav, are from, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Darosh Darash Yosef: Discourses of Rav Yosef Dov Halevi Soloveitchik on the Weekly Parashah,” Rabbi Avishai C. David, editor, pages 16-17, brackets my own) At this point, we may well join the Rav in asking, “What motivated Terah to abandon the luxury of his origins and become a wanderer [at the end of our parasha] …?” We are fortunate that he provides us with a powerful response: The answer is hirhurei teshuvah – stirrings of repentance. Here the patron of the idolaters, a well-known manufacturer of idols, revered and respected by everyone, suddenly abandons everything. Apparently, he realized that all he stood for was absurd and that his son Abram was correct, and Abrams’s ideas reflected the divine truth. He then reappears as a baal teshuvah, one who has repented, and is responsible for the move [at the end of our parasha] to Haran, towards Eretz Yisrael, to begin his life anew. The Rav’s words are quite reminiscent of a passage that appears in the Rambam’s Mishneh Torah regarding a late-in-life baal teshuvah: Even if he transgressed throughout his entire life and repented on the day of his death and died in repentance, all his sins are forgiven as [Sefer Kohelet, 12:2] continues: “Before the sun, the light, the moon, or the stars are darkened and the clouds return after the rain...” - This refers to the day of death. Thus, we can infer that if one remembers his Creator and repents before he dies, he is forgiven. (Hilchot Teshuvah II:1, translation, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger) Terah’s transformation from idol worshipper to baal teshuvah is a powerful message to us all. This teaches us that no matter how far away we may be from the Holy One blessed be He, we may nevertheless return to His welcoming arms and overflowing mercy. With Hashem’s help, may we learn from Terah’s example and ever strive to be better tomorrow than we are today. V’chane yihi ratzon. Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org/ using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Megillat Esther may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link.  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, Shayna Yehudit bat Avraham Manes and Rivka, the refuah shlaimah of Shoshana Elka bat Etel Dina, Devorah bat Chana, Chaya Mindel bat Leah Basha and Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. Shemini Atzeret occurs at the end of Succot. As Midrash Bereshit Rabbah notes, however, it is a chag bifnei atzmo (festival in its own right), rather than a part of Succot. (100:7) This is clearly indicated in the Torah’s introduction to the unique sacrifice for this day, wherein the following formulation is found: “The eighth day shall be a restriction for you; you shall not do any laborious work.” (Bamidbar 29:35, translation, Artscroll Chumash). This verse stands in stark contrast to the preceding pasukim (verses) that refer to the Intermediate Days of Succot (Chol HaMoed) and, therefore, deploy the expression, “And on day…,” indicating they are a continuation of the first day of the festival. In Sefer Vayikra 23:36 and Sefer Bamidbar 29:35, the term, “the eighth day,” is coupled with the expression “Atzeret.” Rashi (1040-1105), in his gloss on our verse from Sefer Vayikra, provides us with a particularly famous and fascinating metaphoric explication of the term “Atzeret” that is partially based upon Talmud Bavli, Succah 55b: [What does “Atzeret” mean?] I [Hashem] will keep you back with Me [one more day]. This is similar to the case of a king who invited his children to a banquet for a certain number of days. When the time arrived for them to take their leave he said: “My children, I beg of you, stay one more day with me; your departure is so difficult for me!” Rashi is homiletically teaching us a profound lesson: Hakadosh Baruch Hu (the Holy One Blessed be He) passionately loves us. Moreover, like the earthly king, the King of Kings has just “spent” a number of days with us wherein we have dedicated ourselves to His service. We have rejoiced in our succot, and sung Hallel with our lulav and etrog. We have had beautiful festive meals and inspiring tefilot (prayers). Yet, our Creator wants more of us. He wants to rejoice with us one day more in order to strengthen the unique bond that exists between us. We do not have to wait, however, for the arrival of Shemini Atzeret to feel Hashem’s love surrounding us. If we are sensitive to the daily words of the tefilot, and carefully concentrate upon their sublime meaning, we can readily hear the message of G-d’s powerful devotion to us. The first morning tefilah that we encounter that explicitly describes Hashem’s affection for us is that of the second bracha (blessing) prior to the recitation of the Shema. It begins with the words “Ahavah rabbah,” and states: “With an abundant love have You loved us, Hashem, our G-d…” It concludes with: “Blessed are You Hashem, Who chooses His people Israel with love.” (Translation, Artscroll Siddur) Significantly, the text does not state “Who chose His people Israel with love,” which would have referred to an historical choice lost long ago in the distant sands of time. Instead, our Sages formulated the prayer in the present tense, i.e., Hashem continuously chooses us in love. This illustrates the tremendous depth of care and concern our Creator has for us. Two explicit statements of Hashem’s depth of connection to us are found in the Amidah (Shmoneh Esrei). In the very first bracha we encounter the phrase “l’ma’an sh’mo b’ahavah” (“for His Name’s sake, with love”). In the blessing known as “Re’tzeh”, we find the phrase: “u’tefilatom b’ahavah tikabale b’ratzon” (“and their prayer accept with love and favor.”) In sum, if we but listen to what we are saying in our prayers on a daily and ongoing basis, we will sense Hashem’s love enveloping us. Little wonder, then, that Megillat Shir HaShirim is the ultimate metaphor for the relationship that obtains between Hashem and the Jewish people. Shemini Atzeret’s message of G-d’s love for us, as reflected, as well, in the words of our tefilot, is a crucial one indeed. It teaches us that we are not alone; for no matter how difficult our daily struggles may be, Hashem is ever our beloved soulmate who continually searches for us in order to bestow His love upon us. In a world that is so often frightening and alienating, this is a message that we continually need to hear. May it be Hashem’s will that we will ever be deserving of His devotion and everlasting love. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom and Chag Sameach! Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on http://www.yutorah.org/ using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on this link: http://bit.ly/2jrPl2V.  Rabbi David Etengoff Dedicated to the sacred memories of my mother, Miriam Tovah bat Aharon Hakohen, father-in-law, Levi ben Yitzhak, sister-in-law, Ruchama Rivka Sondra bat Yechiel, sister, Shulamit bat Menachem, Chaim Mordechai Hakohen ben Natan Yitzchak, Yehonatan Binyamin ben Mordechai Meir Halevi, Avraham Yechezkel ben Yaakov Halevy, Shayna Yehudit bat Avraham Manes and Rivka, the refuah shlaimah of Shoshana Elka bat Etel Dina, Devorah bat Chana, Chaya Mindel bat Leah Basha and Yitzhak Akiva ben Malka, and the safety of our brothers and sisters in Israel and around the world. The Festival of Succot contains two major mitzvot, dwelling in the Succah on the night of the 15th of Tishrei, and the taking of the Arba’at ha-Minim (the Four Species). Both of these acts are in the halachic category of mitzvot aseh sh’hazman grama (time bound Positive Commandments); as such, while women may fulfill these commandments, they are not obligated to do so. This principle is based upon a major Mishnaic period source, “And in all cases of time-bound Positive Commandments, men are obligated and women are exempt.” (Mishna Kiddushin 1:7) The following Midrashic interpretation of the Arba’at ha-Minim is particularly intriguing in light of the Mishna’s statement: An alternate explanation: “The fruit of a beautiful tree [etrog]” – this refers to Sarah, since the Holy One blessed be He honored her (sh’hidrah, literally, beautified her) with good health in her old age. As the text states: “Now Abraham and Sarah were old, coming on in years…” (Sefer Bereishit 18:11) “Date palm fronds [lulav]” – this refers to Rivka, for just like a date palm tree has both fruit and thorns, so, too, did Rivka give birth to a tzadik (Ya’akov) and a ra’asha (Eisav). “A branch of a braided tree [hadas]” – This refers to Leah, for just like the hadas is filled with leaves, so, too, was Leah [blessed] with many children. “Willows of the brook [arvei nachal]” – This refers to Rachel, for just like the arvei nachal wither before the other Arba’at ha-Minim, so, too, did Rachel die before her sister [Leah]. (Midrash Vayikra Rabbah, Parashat Emor 30:10, translation and brackets my own) We are immediately confounded by the Midrash’s choice of the Emahot (Matriarchs) as metaphorically representing the Arba’at ha-Minim. After all, what is their connection if, as we have seen, women are exempt from mitzvot aseh sh’hazman grama? In my estimation, the Midrash followed this path in order to teach us a crucial lesson: Judaism is comprised of two beautiful and equally vital Massorot (traditions), the Massorah of the Fathers and the Massorah of the Mothers. Given this context, it is fitting and proper for the Midrash to compare the Emahot to the Arba’at ha-Minim. In modern times, there was no greater proponent of this approach than my rebbe and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal (1903-1993), known as “the Rav” by his students and followers: People are mistaken in thinking that there is only one Massorah and one Massorah community; the community of the fathers. It is not true. We have two massorot, two traditions, two communities, two shalshalot ha-kabbalah [chains of Tradition] – the massorah community of the fathers and that of the mothers…What kind of a Torah does the mother pass on? I admit that I am not able to define precisely the masoretic role of the Jewish mother. Only by circumscription I hope to be able to explain it. Permit me to draw upon my own experiences. At this point we are privy to the Rav’s deepest personal reminiscences of his beloved mother: I used to have long conversations with my mother. In fact, it was a monologue rather than a dialogue. She talked and I “happened” to overhear. What did she talk about? I must use an halakhic term in order to answer this question: she talked me-inyana de-yoma [about the halakhic aspects of a particular holy day]. I used to watch her arranging the house in honor of a holiday. I used to see her recite prayers; I used to watch her recite the sidra [Torah portion] every Friday night and I still remember the nostalgic tune. I learned from her very much. What was the essence of that which the Rav learned from his mother? What gift did she give him that changed his being and perception of the world? As he states in his unique and unparalleled manner: Most of all I learned that Judaism expresses itself not only in formal compliance with the law but also in a living experience. She taught me that there is a flavor, a scent and warmth to mitzvot. I learned from her the most important thing in life – to feel the presence of the Almighty and the gentle pressure of His hand resting upon my frail shoulders. Without her teachings, which quite often were transmitted to me in silence, I would have grown up a soulless being, dry and insensitive. (Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, “A Tribute to the Rebbitzen of Talne,” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought, 1978, Vol. 17, number 2, pages 76-77) It is, and perhaps always has been, the unique privilege of Jewish women to enable our people to “… feel the presence of the Almighty and the gentle pressure of His hand resting upon [our] frail shoulders.” Therefore, when we rejoice with the Arba’at ha-Minim this Succot, let us remember the Midrash’s essential and powerful message, to embrace both the Massorah of the Mothers and the Massorah of the Fathers, so that we may fulfill this mitzvah as a “living experience” in all its “flavor, scent and warmth.” With Hashem’s help, may we be zocheh (merit) to do so. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom and Chag Sameach! Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org They may also be found on YUTorah.org using the search criteria of Etengoff and the parasha’s name. The email list, b’chasdei Hashem, has expanded to hundreds of people. I am always happy to add more members to the list. If you have family or friends you would like to have added, please do not hesitate to contact me via email mailto:[email protected]. *** My audio shiurim for Women on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on this link: http://bit.ly/2jrPl2V. |

Details

Archives

July 2024

AuthorTalmid of Rabbi Soloveitchik zatzal Categories |

- Blog: Rabbi David Etengoff: Parashat HaShavuah

- Sefer Bereishit 5784&5785

- Sefer Shemot 5784&5785

- Sefer Vayikra 5784&5785

- Sefer Bamidbar 5784 &5785

- Sefer Bereishit 5782&5783

- Sefer Shemot 5782&5783

- Sefer Vayikra 5782&5783

- Sefer Bamidbar 5782&5783

- Sefer Devarim 5782&5783

- Sefer Bereishit 5780& 5781

- Sefer Shemot 5780&5781

- Sefer Vayikra 5780&5781

- Sefer Bamidbar 578&5781

- Sefer Devarim 578&5781

- Sefer Bereishit 5778&5779

- Sefer Shemot 5778&5779

- Sefer Vayikra 5778&5779

- Sefer Bamidbar 5778&5779

- Sefer Devarim 5778&5779

- Sefer Bereishit 5776&5777

- Sefer Bereishit 5774&5775

- Sefer Bereishit 5772&5773

- Sefer Bereishit 5771&5770

- Sefer Shemot 5776&5777

- Sefer Shemot 5774&5775

- Sefer Shemot 5772&5773

- Sefer Shemot 5771&5770

- Sefer Vayikra 5776&5777

- Sefer Vayikra 5774&5775

- Sefer Vayikra 5772&5773

- Sefer Vayikra 5771&5770

- Sefer Bamidbar 5776&5777

- Sefer Bamidbar 5774&5775

- Sefer Bamidbar 5772&5773

- Sefer Bamidbar 5771&5770

- Sefer Devarim 5776&5777

- Sefer Devarim 5774&5775

- Sefer Devarim 5772&5773

- Sefer Devarim 5771&5770

RSS Feed

RSS Feed