Rabbi David Etengoff The beginning of our parasha focuses upon a variety of laws that pertain solely to the kohanim. From a halachic perspective, they have little to do with the majority of the Jewish people, as the kahunah is a biologically endowed status. Yet, from a broader perspective, all members of the Jewish people have the inherent ability to be “kohanim.” How can we actualize this innate spiritual potential to be kohanim? Two pasukim in Sefer Shemot help us answer this question: “And now, if you obey Me and keep My covenant, you shall be to Me a treasure out of all peoples, for Mine is the entire earth. And you shall be to Me a kingdom of priests (mamlechect kohanim) and a holy nation…” (19:5-6, this and all Tanach translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach, with my emendations). Rashi (1040-1105) rejects the literal translation of mamlechect kohanim as a “kingdom of priests.” Instead, he opines that the correct explication of “mamlechect kohanim” is “a kingdom of princes,” since, as noted, we cannot all be kohanim. The Seforno (1470-1550), however, takes an entirely different approach: Precisely by being kohanim you will be chosen (segulah). You will be a kingdom of priests in the sense that you will explain and teach [the existence and knowledge of G-d] to all manner of people. In that way, everyone will call upon Hashem and worship Him, shoulder to shoulder. As it says in Sefer Yeshayahu [61:6]: “And you will be called the Priests of Hashem.” According to the Seforno, our foremost obligation is to bring spiritual illumination to humankind as an ohr l’goyim (“light unto nations,” Sefer Yeshayahu 42:6 and 49:6). It is our responsibility to act as the moral compass of humanity by embodying the highest standards of ethical behavior, and thereby be metakane ha’olam b’malchut Shakai--perfect the Universe through the proclamation of Hashem’s sovereignty.” In this way, we pave the way for all people to recognize His greatness and glory. Rabbeinu Shimson Raphael Hirsch (1808-1888) presents a complementary approach to the Seforno’s analysis. He explains Sefer Shemot 19:6 in terms of our people’s mission to be kohanim and the resulting positive impact we can have on humankind: Each one of you will be a “kohane” in the sense that you will accept upon yourselves My hegemony [My power to rule] in every action that you will do. In so doing, you will take upon yourselves the yoke of the kingdom of Heaven in its overarching sense. One will then be able to spread the knowledge of, and loyalty to, Hashem through the words of one’s mouth and the performance of one’s deeds. (Translation from the Hebrew my own) These presentations serve as compelling descriptions of our role as Hashem’s servants. Beyond a doubt, however, it is the Rambam (1135-1204) who gives this concept its most powerful voice. Moreover, he underscores the notion that anyone, Jew, or gentile, can be sanctified to the point that they can emulate the levi’im and kohanim. As such, everyone can potentially become a light unto nations: Not only the tribe of Levi, but any one of the inhabitants of the world whose spirit generously motivates him and understands with his wisdom [how] to set himself aside and stand before Hashem to serve Him and minister to Him and to know Hashem, proceeding justly as Hashem made him…is as sanctified as the holy of holies. Hashem will be His portion and heritage forever and will provide what is sufficient for him in this world like He provides for the kohanim and levi’im. And thus, David declared: “Hashem is the lot of my portion; You are my cup, You support my lot.” (Sefer Tehillim 16:5, Rambam, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Shemitah v’Yovel 13:13, translation, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger) May we be counted among those who strive to create a mamlechect kohanim, and thereby dedicate ourselves to the holy task of tikkun haolam (perfecting the Universe). V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav

0 Comments

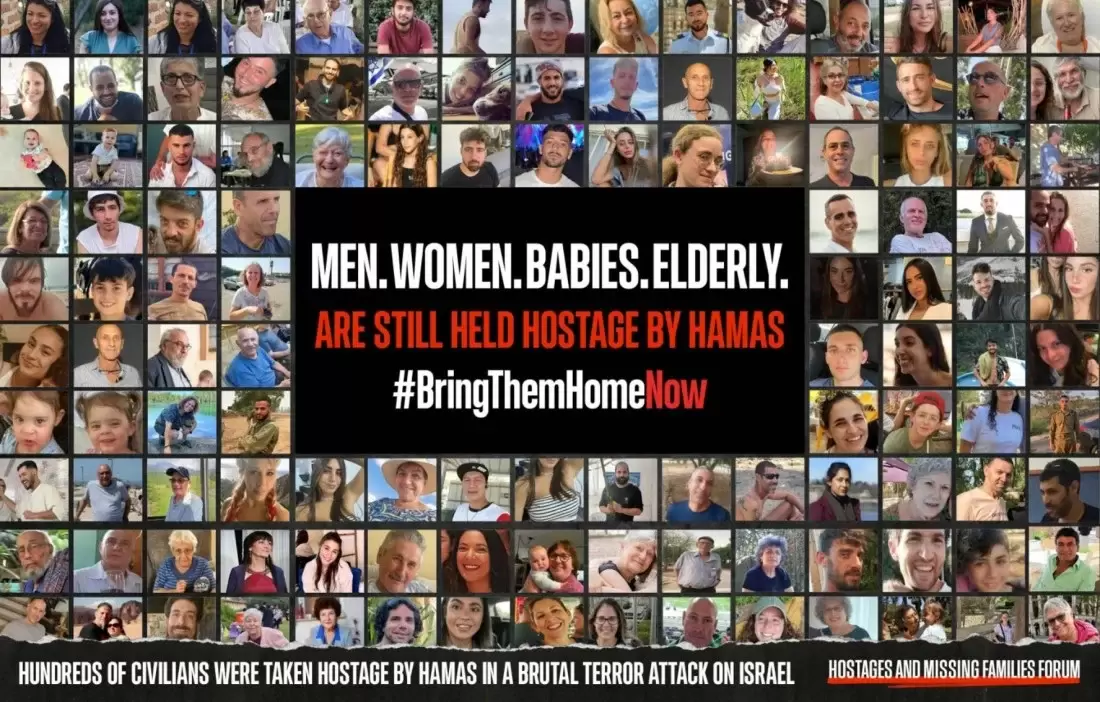

Rabbi David Etengoff One of the most celebrated mitzvot of our parasha is “v’ahavta l’reicha kamocha —and you shall love your fellow Jew like yourself.” (Sefer Vayikra 19:18) Rashi (1040-1105), citing the Midrash Sifra to Sefer Vayikra, notes: “Rabbi Akiva said: ‘This is an all embracing principle of the Torah.’” (19:45, translation my own) Perhaps it is Rabbi Akiva’s unparalleled intellectual greatness, or his heroic gesture of teaching Torah to his students during the height of the 130’s CE Hadrianic persecutions, that caused his words to become part of the moral fabric of the Jewish nation. Either way, whenever we think of our personal responsibility towards one another, the Torah’s verse, and Rabbi Akiva’s expression, are writ large in the collective consciousness of our people. Talmud Bavli, Shabbat 31a, is one of the best-known sources in Rabbinic literature wherein we find a restatement and implicit discussion of the phrase, “v’ahavta l’reicha kamocha:” On another occasion it happened that a certain non-Jew came before Shammai and said to him, “Make me a convert, on the condition that you teach me the entire Torah while I stand on one foot.” Thereupon he repulsed him with the builder’s staff which was in his hand. When he went before Hillel, he converted him and said to him, “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor: that is the entire Torah, while the rest is commentary; [now] go and learn it.” (Translation, The Soncino Talmud with my emendations) In his commentary on the Torah, Kli Yakar, Rabbi Shlomo Ephraim ben Aaron Luntschitz (1550 –1619), maintains that the Talmud’s phrase, “what is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor,” is a reformulation and an interpretation of “v’ahavta l’reicha kamocha.” In addition, Rav Luntschitz carefully examines the interaction between Hillel and the would-be convert, and in so doing reveals the underlying intent of the latter’s famous words, “teach me the entire Torah while I stand on one foot.” According to Rav Luntschitz, the non-Jew who came before both Shammai and Hillel was no prankster or joker—even though Shammai seemed to have viewed him as such. Instead, and this is apparently how Hillel perceived him, the aspiring convert was a potential ger tzedek, a truly righteous individual, who deeply desired to accept the Master of the Universe and His Torah, live according to His mitzvot and join our people. As Rav Luntschitz suggests: “[The potential ger tzedek] absolutely wanted [the essence] of all of the Torah’s mitzvot presented to him in such a manner that they would have one [unifying] principle, and this is what he actually meant by the words “on one foot.” (This and the following translation and brackets my own) At this juncture, Rav Luntschitz analyzes the ger tzedek’s ultimate purpose in making his request: As a result of this [“on one foot” notion,] he would be able to understand all of the mitzvot [with particular emphasis upon the proper ethical behaviors that the Torah commands between man and his fellow man]. He desired this so that he would never forget [the meaning of the mitzvot,] since this would be all too easy for a convert who had not studied anything whatsoever regarding the commandments during his youth...Thus, his intention [when he deployed the unusual phrase, “teach me the entire Torah while I stand on one foot,”] was [for Hillel] to teach him something that could be said quickly and was comprised of few words. This, then, would be the fundamental concept of the Torah, and “the one foot” that he needed; for as a result of this idea, he would be able to remember [and understand] all of Hashem’s mitzvot. In Rav Luntschitz’s estimation, the ger tzedek was driven by the highest spiritual ardor in order to understand the authentic meaning of the mitzvot. In many ways, therefore, he serves as an ideal role model for us all, since far too often, we become overwhelmed by the challenges of daily living and forget that the Torah and mitzvot should appear to us as holy gifts from the Almighty. The ger tzedek helps us refocus our priorities, so that we may redouble our energies and create a spiritually suffused relationship with the Master of the Universe. With His help and our fervent desire, may this be so. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff ה' יעזור וירחם על אחינו כל בני ישראל, בארץ ישראל ובכל חלקי הארץ Yimot hamashiach (Days of the Mashiach), like many popular terms, is frequently used and just as often little understood. Yeshayahu describes it in this manner in the haftorah for the last day of Pesach: And a wolf shall live with a lamb, and a leopard shall lie with a kid; and a calf and a lion cub and a fatling [shall lie] together, and a small child shall lead them. And a cow and a bear shall graze together, their children shall lie; and a lion, like cattle, shall eat straw. And an infant shall play over the hole of an old snake and over the eyeball of an adder, a weaned child shall stretch forth his hand. (11:6-8, translation, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Shmuel (165-257 C.E.), known as one of the greatest Talmudic Sages, understands these pasukim in a metaphoric sense. As such, instead of a world wherein the instinctual behaviors of the animal kingdom will be radically altered, we will be blessed to live in a time when our people will be free from the yoke of our oppressors: “There will be no difference between our world and the days of the Messiah except for the cessation of the domination of the kingdoms of the world [over the Jewish people].” (Talmud Bavli, Sanhedrin 99a, translation and brackets my own) Thus, for Shmuel, yimot hamashiach will be a time of complete socio-political freedom for the Jewish people. In his halachic magnum opus, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Melachim 11:1 and 12:1 and 2, the Rambam (1135-1204) elucidates Shmuel’s position in this fashion: King Messiah will arise in the future and return the kingship of David to its former greatness and glory. He will rebuild the Holy Temple and gather all of the exiles to the Land of Israel. All of the laws will be in effect during his days just as they were in earlier times. We will [once again] offer korbanot (animal offerings) and keep the laws of the Sabbatical and Jubilee years just like all of the other laws stated in the Torah. One ought not to think that in the days of the Messiah anything will change in the nature of the world (m’minhago shel haolam), or that there will be some new creation within nature (b’ma’aseh Bereishit). Rather, the world will continue in its normal fashion. The passage in Yeshayahu that states “And a wolf shall live with a lamb, and a leopard shall lie with a kid…” is merely a metaphor. Rather, it really means that the Jewish people will live in comfort and without fear of the evil non-Jewish nations who are symbolically represented by the terms “wolf” and “leopard.” Our Sages stated: “There will be no difference between our world and the days of the Messiah except for the cessation of the domination of the kingdoms of the world [over the Jewish people].” (Translation, underlining, and brackets my own) One is immediately struck by the purely naturalistic position taken by the Rambam. The reinstitution of the Davidic monarchy “to its former greatness and glory” in the person of the true Messiah is the necessary and fundamental criterion for the achievement of all other Jewish eschatological goals. “Former greatness and glory” refers to uncontested Jewish hegemony over our own G-d-promised land. Pragmatically, it means that the unending political pressures faced by the modern State of Israel will cease. Moreover, since all countries will recognize our beloved nation as Hashem’s unique dwelling place among humankind, it will be preeminent in the world. This will be a natural result of the nations of the world “returning to the true faith,” that is, monotheism (12:5). Once we are politically free and no longer beholden to any earthly power, the Melech Hamashiach will “rebuild the Holy Temple and gather all of the exiles to the Land of Israel.” The Anshei Kenesset HaGadolah (Men of the Great Assembly) gave powerful voice to these aspirations in two brachot of the Shemoneh Esrei: And may You return to Your holy city in mercy, and dwell therein as You have spoken. And may You build it soon and in our days as a permanent construction. And may the throne of King David rapidly be re-established therein. Blessed are You Hashem, He who builds Jerusalem. Sound the great shofar [whose clarion call] declares our freedom. And raise up our standard to gather around all of our exiles and gather us all together from the four corners of the earth. Blessed are You Hashem, He who gathers the exiles of His people Israel. (Translation and brackets my own) May this Pesach be the time wherein these tefilot will be answered. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom and Chag Kasher v’Sameach Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff ה' יעזור וירחם על אחינו כל בני ישראל, בארץ ישראל ובכל חלקי הארץ Our natural inclination at this time of the year is to focus upon the phrase, zacher l’yetziat mitzraim —a remembrance of the Exodus from Egypt. This is the case, since one of the major mitzvot of Pesach evening is none other than l’saper b’yetziat mitzraim—to tell the story of the departure from Egypt. While this is a key element of our thoughts during the course of the Seder, the Torah also reminds us, no less than five times, “And you shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt...” (Sefer Devarim 5:15, 15:15, 16:12, 24:18 and 24:22, this and all Tanach translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach with my emendations) As such, while we are obligated to focus upon our joyous march to freedom on the night of Pesach, we are equally mandated to remember our 210-year ordeal of backbreaking servitude and abject misery at the hands of our heartless Egyptian taskmasters. Two of the five instances wherein the Torah enjoins us to “remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt...” explicitly discuss our responsibility to treat the stranger, orphan, and widow in an equitable and righteous manner: You shall not pervert the judgment of a stranger or an orphan, and you shall not take a widow's garment as security [for a loan]. You shall remember that you were a slave in Egypt, and Hashem, your G-d, redeemed you from there; therefore, I command you to do this thing. (Sefer Devarim 24:17-18) When you beat your olive tree, you shall not pick all its fruit after you; it shall be [left] for the stranger, the orphan, and the widow. When you pick the grapes of your vineyard, you shall not glean after you: it shall be [left] for the stranger, the orphan, and the widow. You shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt: therefore, I command you to do this thing. (24:20-22) These verses urge us to guard the rights and privileges of the most powerless members of Jewish society by reminding us that our entire nation was once completely vulnerable and subject to the diabolical control of Pharaoh and his henchmen. Therefore, as a people and as individuals, we should ever remember our Egyptian servitude and become acutely sensitive to the needs of those who need our help to live dignified and meaningful lives. In other words, the Torah is commanding us to practice the highest standards of social justice. The Rambam (Maimonides, 1135-1204) codifies our moral and halachic imperative to actively provide for the needs of those most at risk in a well-known halacha regarding the mitzvah of simchat Yom Tov (rejoicing during the Yom Tov meal): When a person eats and drinks [in celebration of a holiday], he is obligated to feed converts, orphans, widows, and others who are destitute and poor. In contrast, a person who locks the gates of his courtyard and eats and drinks with his children and his wife, without feeding the poor and the embittered, is [not indulging in] rejoicing associated with a mitzvah, but rather the rejoicing of his belly. (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Yom Tov 6:18, translation, Rabbi Eliyahu Touger with my emendations) The Rambam is teaching us a profound life lesson that goes far beyond a specific Yom Tov-based halacha, namely, kol Yisrael arevim zeh bazeh—every Jew is personally responsible for the welfare of every other Jew, and no one should be left behind. Little wonder, then, that in the opening words of the Haggadah we declare as one: This is the bread of affliction that our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt. All those who are hungry, let them enter and eat. All who are in need, let them come celebrate the Passover. Now we are here. Next year in the land of Israel. This year we are enslaved. Next year may we be free. (http://www.mazoncanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/2015-Passover-Resource.pdf) B’shanah haba b’yerushalayim habanuyah!—may we join as one united people in the rebuilt Beit HaMikdash soon, and in our days. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom and Chag Kasher v’Sameach Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff ה' יעזור וירחם על אחינו כל בני ישראל, בארץ ישראל ובכל חלקי הארץ The primary focus of our parasha is the illness known as tzaraat. In his Commentary on the Torah, the Rashbam (1080-1158) presents the unique nature of this disease: All of the sections dealing with the negayim (afflictions) affecting people, garments, houses, and the manner in which they appear as well as the number of days requiring sequestering, the white, black, and golden identifying hairs—cannot be understood by following the simple and direct meaning of the text. Neither may we rely upon standard human knowledge and expertise [that is, current medical information]. Instead, we must follow the analysis of the Sages, their decrees, and the inherited body of knowledge that they received from the earliest Sages. This is the essence [of this matter]. (Introduction to Parashat Tazria, translation and brackets my own) In the Rashbam’s view, tzaraat can be understood solely from the Torah’s standpoint, rather than from a physiological or medical perspective. This is because its etiology does not follow the normative laws of biology. Instead, it is a spiritually-based ailment that manifests in a physical fashion. The Torah presents us with three types of tzaraat: “If a man has a se’et, a sapahat, or a baheret on the skin of his flesh, and it forms a lesion of tzaraat on the skin of his flesh, he shall be brought to Aharon the Kohen, or to one of his sons, the Kohanim.” (Sefer Vayikra 13:1, this and all Tanach translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach, with my emendations) Midrash Vayikra Rabbah, Tazria 15:9, identifies each of these categories as metaphorically representing one of the ancient nations who either violently injured or sought to harm our people. Thus, “se’et [a rising] is Babylonia... sapahat [a scab] is [the kingdom of the] Medes... and baharet [a bright spot] is Greece.” (This and the following translation, Darosh Darash Yosef: Discourses of Rav Yosef Dov Halevi Soloveitchik on the Weekly Parashah, Rabbi Avishai C. David editor, pages 227-228) Our midrash notes that Haman, who attempted to eradicate our people, was the most infamous member of the ancient Medes: “[The kingdom of the] Medes raised Haman the wicked, who crawled like a snake, as it is written, ‘On your belly you shall go.’” (Sefer Bereishit 3:4) My rebbe and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal (1903-1993), known as “the Rav” by his students and followers, builds upon our midrash and describes Haman in the following fashion: ...[he] slithered like a snake but was puffed up with arrogance. A fawning personality, he lacked dignity. His sycophantic behavior resulted in his becoming prime minister to King Ahashverosh. Yet, Haman was no leader. A weak and spineless man, he used flattery to get ahead. Thinking that it would save his life, he behaved in a servile manner toward Esther even after she exposed him. Like other haughty people, he did not realize how base he was, that he was actually a form of sapahat. (Darosh Darash Yosef, page 231, underlining and italics my own) In the Rav’s view, the haughty and arrogant Haman emerges as a base and slithering being who lacked all manner of dignity to the extent that “he was actually a form of sapahat.” What does it mean for a person to be “a form of sapahat,” to be a scab on the body of humanity in general, and an enemy of the Jewish people in particular? The Rav indirectly addresses this question in his analysis of those who demonstrate ga’avah (arrogant pretentiousness) and pursue kavode (false honor): If, however, one pursues these qualities, then they are false and reprehensible. This is particularly the case if one actively deceives himself and pretends to be someone other than who he really is...The greatest falsehood takes place when a person lies to himself. (Rabbi Yosef Dov Halevi Soloveitchik, Yimei HaZikaron, page 208, Sifiriyat Elinor, editor, translation and brackets my own) Haman is the ultimate example of an individual who “actively deceives himself and pretends to be someone other than who he really is.” He convinced himself that he had geut--grandeur, when in fact, he was merely “puffed up with arrogance” born of self-delusion and grandiose visions. Moreover, the Rav asserts, Haman’s ga’avah was nothing other than “a negative character trait, a form of spiritual tzaraat...Therefore, we must avoid ga’avah and be careful not to behave like Haman, who thought that only he was worthy of honor.” (Darosh Darash Yosef, page 231) As such, according to the Rav, Haman epitomized the notion that “the greatest falsehood takes place when a person lies to himself.” The Rav continues his presentation and emphasizes that, in stark contrast to the spiritual tzaraat of ga’avah demonstrated by Haman and others of his ilk, Hashem has true geut and must therefore be recognized as He Who acts with grandeur. As King David and Yeshayahu the prophet taught us so long ago: Hashem has reigned; He has attired Himself with majesty (geut)... (Sefer Tehillim 93:1) In the land of uprightness, he [the evil one] deals unjustly, and he does not see the majesty (geut) of Hashem. (Sefer Yeshayahu 26:10) Sing to Hashem for He has performed majestic deeds (geut); this is known throughout the land. (Sefer Yeshayahu, 12:5) As the Rav underscores many times, “The principle of imitatio dei [imitating Hashem’s behaviors] demands that we emulate G-d’s attributes.” (Darosh Darash Yosef, page 231) Therefore, may we always reject ga’avah and the spiritual tzaraat it represents, and embrace the authentic majesty of geut Hashem V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff ה' יעזור וירחם על אחינו כל בני ישראל, בארץ ישראל ובכל חלקי הארץ This Shabbat we will read Parashat HaChodesh which focuses on Rosh Chodesh, the first mitzvah Hashem commanded to the entire Jewish people: “This month shall be to you the head of the months; to you it shall be the first of the months of the year.” (Sefer Shemot 12:2, this and all Tanach translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Rosh Chodesh’s historical and legal significance to our people is presented in a treasure trove of halachic analyses and aggadic interpretations that give voice to its remarkable import. In particular, Rabbi Elazar ben Arach, the greatest of all the students of Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai (Pirkei Avot II: 9-10), looms large in the list of famous Torah personalities associated with this special day: Rabbi Chelbo said: The wine of Perugitha and the water of Diomsith cut off the Ten Tribes from Israel [due to their powerful hedonistic and anti-Torah influences, Rashi]. Rabbi Elazar ben Arach visited those places. He was attracted to them [the wine and the bath waters] and [as a result,] his learning was uprooted [that is, he forgot it, Rashi]. When he returned [to the community of scholars], he arose to read the Torah. He wanted to read, “HaChodesh hazeh lachem” (“This month shall be to you…”) [instead,] he read “HaCharesh hayah libbam” (“Their hearts were silent”). But the scholars prayed for him, and his learning returned. (Talmud Bavli, Shabbat 147b, translation, The Soncino Talmud with my emendations) In his commentary on the Torah entitled, “Kedushat Tzion,” the second Bobover Rebbe, HaRav Ben-Zion Halberstam zatzal (1874-1941), suggests the following interpretation of our passage: “We must understand the words of our Sages and the quizzical nature as to why Rabbi Elazar ben Arach was called upon to read the specific parasha of ‘HaChodesh hazeh lachem.’” Rav Halberstam’s exploration of the connection between Rabbi Elazar and Rosh Chodesh sheds light upon the concept of mitzvah goreret mitzvah (one commandment brings another in its wake, Pirkei Avot 4:2) and the problems associated with mitzvat anashim m’lumdah (the rote performance of a mitzvah): The meforshim ask, “Does the phrase, ‘mitzvah goreret mitzvah’ really imply that an individual who performs one mitzvah will henceforth be like an unceasing river [of mitzvot observance], since one mitzvah brings another in its wake so that the entire rest of his life will be, by definition, mitzvot-suffused?” (Kedushat Tzion, Parashat Bo, page 98, this, and the following translations, my own) Rav Halberstam summarizes the meforshim’s response to this question in this manner: The commentators address this difficulty by noting that the uniquely valuable reward inherent in the phrase “mitzvah goreret mitzvah” applies solely to a commandment that is performed with deep intention (“b’kavanat halev”) and in its proper manner—then, and only then, does it lead one to perform another mitzvah. If, however, the commandment is performed as a mitzvat anashim m’lumdah, that is, without proper intention, then it will not lead one to undertake another mitzvah. In an interpretative tour de force, Rav Halberstam opines that Rabbi Elazar ben Arach was frightened after reading “HaCharesh hayah libbam” in place of our pasuk’s phrase, “HaChodesh hazeh lachem.” Based upon his abiding humility, Rabbi Elazar believed his error resulted from having “failed to properly concentrate when fulfilling the commandments on prior occasions,” for if this were not the case, the great mitzvah of Rosh Chodesh, the subject of his Torah reading, should have protected him. After all, since Rosh Chodesh was the first mitzvah given to the entire Jewish people, it should engender mitzvah goreret mitzvah. Rabbi Elazar, therefore, concluded that his mitzvot observance must have been on the low level of mitzvat anashim m’lumdah, which resulted in the loss of the reward and protection of mitzvah goreret mitzvah, and made him susceptible to the lure of hedonistic pursuits and the subsequent loss of his Torah knowledge. According to Rav Halberstam, however, Rav Elazar ben Arach’s “colleagues knew full well that, in truth, he had performed prior mitzvot with the requisite intentionality,” and as a result, “prayed for mercy on his behalf and his learning returned.” This poignant episode underscores the great power and holiness of Rosh Chodesh, and its remarkable significance in the thought of Chazal. As such, may the merit of our heartfelt observance of this mitzvah bring us bountiful blessings from Hashem and hasten the coming of the Mashiach, soon and in our days. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff ה' יעזור וירחם על אחינו כל בני ישראל, בארץ ישראל ובכל חלקי האר Like much of Sefer Vayikra, our parasha focuses on the korbanot. Accordingly, the second verse presents the mitzvah of the korban olah: “Command (tzav) Aharon and his sons, saying, ‘This is the law of the burnt offering: That is the burnt offering which burns on the altar all night until morning, and the fire of the altar shall burn with it.’” (Sefer Vayikra 6:2, this and all Rashi and Tanach translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach) Rashi (1040-1105), basing himself on Midrash Sifra on our verse and Talmud Bavli, Kiddushin 29a, explains “tzav” in this manner: “The expression tzav always denotes urging [to promptly and meticulously fulfill a particular commandment] for the present (miyad) and for future generations (v’ledorot).” The word, “miyad,” makes perfectly good sense in this context, since the kohanim were able to offer the korban olah during the time of the Mishkan and Beit HaMikdash. The term, “v’ledorot,” however, seems problematic, as we have not had a Mishkan or Beit HaMikdash for nearly 2,000 years. My rebbe and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal (1903-1993), known as “the Rav” by his students and followers, expands on our question: What is the meaning of the word ledoros (for future generations) in this context? The mitzvos of mezuzah, tefillin and Shabbos are clearly ledoros. Thousands of years have gone by, and these mitzvos are observed as they had been when they were originally given. But in what way are the mitzvos of the Mishkan practiced today? There has been no korban tamid [daily offering] for almost two thousand years! In what sense does the mitzvah of offering korbanos continue? (Sefer Vayikra Chumash Mesoras HaRav, with commentary based upon the teachings of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, edited by Dr. Arnold Lustiger, page 33) The Rav begins his answer by citing a midrashic passage in Talmud Bavli, Megillah that presents a fascinating dialogue between Hashem and Avraham Avinu: Abraham asked how he was to know that G-d would not forsake Israel if they sinned. G-d answered, “In the merit of the [Temple] sacrifices.” Abraham insisted that this merit is fine when these sacrifices are in existence, but what was to happen after the destruction of the Temple? G-d replied that if the Children of Israel learned the laws surrounding the sacrifices, He would consider their study as a virtual sacrificial offering. When we cannot offer sacrifices, we recite the halachos [laws] pertaining to them as a substitute. (31b) In short, the study of the laws of korbanot enables us to bring “virtual sacrificial offerings” and fulfill these mitzvot in a substitute manner. At this juncture, the Rav extends his interpretation of “virtual” to include the Beit HaMikdash itself: There is a Mikdash in our days as well—not physically, but through halachic study. This is the mesorah [the passing down from each generation to the next] of Torah Sheb’al Peh, the Oral Law. Today, we read Parashas Shekalim as if the Beis Hamikdash was still standing; it is ledoros. Parashas Parah reminds us to be ritually pure so that we may bring the korban pesach. Although we no longer offer a korban pesach, we read Parashas Parah as if the Beis Hamikdash still exists. 2,000 years is a long time to wait for the rebuilding of the Beit HaMikdash. Nonetheless, this vision remains indelibly engraved in our neshamot, and was given powerful voice in the Shemoneh Esrei: Return in mercy to Yerushalayim Your city and dwell therein as You have promised; speedily establish therein the throne of David Your servant, and rebuild it, soon in our days, as an everlasting edifice. Blessed are You Hashem, who rebuilds Yerushalayim. (Shemoneh Esrei, translation, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/867674/jewish/Translation.htm) With Hashem’s overflowing kindness and mercy, may we be zocheh to serve Him in the rebuilt Beit HaMikdash in our time, v’ledorot—and for all generations to come! V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff ה' יעזור וירחם על אחינו כל בני ישראל, בארץ ישראל ובכל חלקי האר This Shabbat we will read Parashat Zachor. According to the Shulchan Aruch, the public reading of this parasha is a Torah-based mitzvah. (Orech Chaim 146:2 and 685:7) In addition, it enables us to fulfill two of the three Taryag Mitzvot associated with Amalek as determined by the Rambam in his Sefer HaMitzvot: “Remember what Amalek did to us,” (Positive Commandment 189) and “We are warned not to forget what ‘the seed’ of Amalek did to us.” (Negative Commandment 59). One of the essential principles of parshanut (Torah exegesis) is the timeless significance of each verse and narrative passage in the Torah. According to Mishnah Yadaim 4:4, however, Sennacherib, the King of Assyria (720-683 BCE approx.), completely destroyed the cohesiveness of all nations and tribes of his time—including Amalek. If this is the case, why does the Torah state three separate, and eternal mitzvot regarding a tribal entity that no longer exists? My rebbi and mentor, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik zatzal (1903-1993), addresses this question in his famous essay of 1956, “Kol Dodi Dofek,” wherein he presents a seminal idea he learned from his father, Rav Moshe Soloveitchik zatzal (1879-1941): At a Mizrachi convention I cited the view expressed by my father and master (Rabbi Moses Soloveitchik) of blessed memory, that the proclamation, “The Lord will have war with Amalek from generation to generation,” (Exodus 17:16) does not only translate into the communal exercise of waging obligatory war against a specific race but includes as well the obligation to rise up as a community against any people or group that, filled with maniacal hatred, directs its enmity against Keneset Israel. When a people emblazons on its banner, “Come, and let us cut them off from being a nation: that the name of Israel may be no more in remembrance,” (Psalms 83:5) it becomes, thereby, Amalek. (Pages 65-66 from the English translation entitled Fate and Destiny) According to this opinion of Rav Moshe Soloveitchik zatzal, Amalek is not a tribe or an ethnicity. Instead, it is a mindset with which we are all too familiar. Unfortunately, this version of Amalek has existed for uncountable years, and will continue to exist until destroyed by Mashiach Tzidkanu. (Rambam, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Melachim 11:4) The Rav underscores this point in the original Hebrew edition of “Kol Dodi Dofek”: “…Amalek still exists in the world. Go and see what the Torah says: ‘a war of Hashem with Amalek throughout all of the generations.’ If so, it is impossible that Amalek will be destroyed from this world before the arrival of the messiah.” (Footnote 23) Accordingly, the Rav writes: “In the 1930’s and 1940’s the Nazis, with Hitler at their head, filled this role. They were the Amalekites, the standard-bearers of insane hatred and enmity during the era just past. Today their place has been taken over by the mobs of Nasser and the Mufti.” Sadly, we can easily substitute Hamas, Hezbollah, Iran, White Supremacists, and today’s world-wide radicalized university community, for the Nazis, Nasar, and the Mufti of yesteryear. Make no mistake about it. Amalek’s goal is to destroy each and every one of us so in order to obliterate Hashem’s name, chas v’shalom, from the world. Antisemitism, coupled with the rejection of the existence and supremacy of Hashem, are the doctrinal principles by which Amalek lives. The Jewish people, in contrast, are Hashem’s true witnesses. Our very existence belies the specious “beliefs” of all Amalekites for all time. How can we stand up and join Hashem in His continuous struggle against the forces of ultimate darkness? The Torah gives us the answer in one word: “Zachor!” We must not be fooled by the duplicity and disingenuous behaviors of today’s Amalekites, regardless of what the media would like us to believe. “From the River to the Sea,” means one thing and one thing only—the attempt to complete Hitler’s Final Solution in our time. May we soon witness the coming of the Mashiach, when the entire world will stand shoulder to shoulder in recognizing Hashem’s truth and glory, and Amalek’s memory will fade into the past. Then, may the words of Zephaniah the prophet be fulfilled before our eyes: “I will make the peoples pure of speech so that they will all call upon the Name of G-d and serve Him with one purpose.” (3:9) V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff ה' יעזור וירחם על אחינו כל בני ישראל, בארץ ישראל ובכל חלקי הארץ Sefer Shemot is a grand journey that takes us from the depths of Egyptian servitude to the construction of the Mishkan wherein Hashem’s Schechinah was revealed to the entire Jewish people. Parashat Pekudei concludes Sefer Shemot and provides Rabbeinu Bahya ben Asher (1255-1340) with the platform to share his vision of the ultimate future that awaits the Jewish people. His presentation begins with a passage based on Midrash Tanchuma: The Holy One blessed be He said: “In this world, I caused my Schechinah to dwell among you in the Beit HaMikdash; [yet,] as a result of your purposeful sins, it departed from you. In the time of the Mashiach (literally, l’atid lavo,) my Shechinah will never move away from you. As the text states: ‘I have placed My holy dwelling place in your midst, and My spirit will never reject you…and you will be My people.’” (Sefer Vayikra 26:11-12, all translations my own) Rabbeinu Bahya presents nine constitutive aspects of l’atid lavo. This analysis includes the reinvigoration of our relationship with Hashem, the transformation of all humankind, and the realization of the promised role of the Jewish people. According to Rabbeinu Bahya, the time of the Mashiach will mark three dynamic changes in our connection to Hashem: Nevuah will return to the Jewish people as in earlier times, the Schechinah will return to its rightful place in the soon-to-be-rebuilt Beit HaMikdash, and wisdom from above (shefa chochmah) will overflow, enabling all of klal Yisrael to fully acquire Hashem’s holy Torah. Moreover, three crucial transformations will impact all humankind: the study and practice of warfare will cease (Sefer Yeshayahu 2:4), new hearts (proper moral principles and ethical behaviors) will replace hearts of stone (Sefer Yechezkel 36:26), and the desire to pursue evil will vanish from the world (ain satan v’ain yetzer hara). In Rabbeinu Bahya’s schema, the realization of the promised role of the Jewish people comprises the third aspect of the Geulah Shlaimah. As glory and honor returns to our nation, Hashem’s hashgacha (Divine Providence) will reach its highest heights, and His majesty, revealed unhidden by the Anan (Cloud of Gory) will be directly visible to us all. Rabbeinu Bahya concludes his eschatological vision with a stirring pasuk from Sefer Yeshayahu that underscores this new level of revelation: “The voice of your watchmen shall be raised in unison, and they shall sing together, for eye to eye they shall see when Hashem returns to Tzion.” (52:8) May this time come soon and in our days, when we will witness the fulfillment of Zechariah’s famous words: “And Hashem shall become King over the entire earth; on that day Hashem shall be one and His name one.” (14:9). V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org. Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav  Rabbi David Etengoff ה' יעזור וירחם על אחינו כל בני ישראל, בארץ ישראל ובכל חלקי הארץ Our parasha begins with Moshe Rabbeinu gathering the entire Jewish people before him: “Moshe called the whole community of the children of Israel to assemble, and he said to them: ‘These are the things that Hashem commanded to make.’” (Sefer Shemot 35:1, all Tanach and Rashi translations, The Judaica Press Complete Tanach with my emendations) At this point, we would expect some sort of listing of “the things that Hashem commanded to make,” instead, we are met with two verses that discuss several aspects of Shabbat: Six days work may be done, but on the seventh day you shall have sanctity, a day of complete rest to Hashem; whoever performs work thereon [on this day] shall be put to death. You shall not kindle fire in any of your dwelling places on the Shabbat day. (35:2-3) These pasukim are followed by 32 verses that discuss the acquisition of the necessary materials to construct the Mishkan and its vessels, and the people’s largesse in providing these needs. Why did Moshe discuss Shabbat in the midst of focusing on “the things that Hashem commanded to make?” In his Commentary on the Torah on our verse, Rashi (1040-1105), based on the Mechilta, suggests the following well-known answer: Six days: “He [Moshe] prefaced [the discussion of the details of] the work of the Mishkan with the warning to keep Shabbat, denoting that it [that is, the work of the Mishkan] does not supersede Shabbat.” In short, Shabbat’s mention prior to the Mishkan depicts its singular import and its precedence over the construction of the Mishkan. This order is reversed in Parashat Ki Tisa, where 11 Mishkan focused pasukim (31:1-11) are stated before Shabbat, and only afterwards do we find: Hashem spoke to Moshe, saying: “And you, speak to the children of Israel and say: ‘Only (ach) keep My Shabbatot! For it is a sign between Me and you for your generations, to know that I, Hashem, make you holy. Therefore, keep Shabbat, for it is a sacred thing for you. Those who desecrate it shall be put to death, for whoever performs work on it, that soul will be cut off from the midst of its people. Six days work may be done, but on the seventh day is a Shabbat of complete rest, holy to Hashem; whoever performs work on the Shabbat day shall be put to death.’” (31:12-14) Our exegetical challenge is now quite clear: Why is the Mishkan mentioned before Shabbat in Parashat Ki Tisa while the opposite order obtains in Parashat Vayakel? In his Torah commentary, Keli Yakar, Rabbi Shlomo Ephraim ben Aaron Luntschitz zatzal (1550 –1619) strengthens this question: It is [almost] always the case in every instance where one mitzvah precedes another mitzvah that the first one is of the essence and sets aside the second one. So, too, do we find in the verse: “You shall observe My Shabbatot and revere My Mikdash. I am Hashem,” (Sefer Vayikra 19:30) wherein Shabbat is given precedence over the Mikdash.” (Sefer Shemot 35:2, this, and the following translations, with my emendations, my own) Based on this idea, Parashat Ki Tisa appears to be an outlier. Rav Luntschitz begins his analysis by noting that Parashat Ki Tisa and Parashat Vayakel have two different speakers. The first features Hashem’s words to Moshe, whereas the second contains Moshe’s address to the Jewish people. Rav Luntschitz suggests that this difference helps us understand why the Mishkan is mentioned first in Ki Tisa and Shabbat is first in Vayakel. In his view, the entire purpose of the Mishkan was to give voice to the new-found glory of the Jewish people after “the Holy One blessed be He forgave the people for the sin of the Egel HaZahav and allowed His Schechinah to rest upon them once again.” This was particularly apropos since, “the Holy One blessed be He is extremely sensitive to the honor of the Jewish people; therefore, [in Parashat Ki Tisa,] He gave precedence of place to the Mishkan [before He mentioned Shabbat].” In contrast, Rav Luntschitz opines that it was proper for Moshe Rabbeinu to mention Shabbat before the Mishkan in Parashat Vayakel since, “the core of Shabbat is the glory of Hashem, may He be blessed...” He builds on these concepts and arrives at the following incisive conclusion: Moshe thought that in order to grant the requisite respect to Hashem, may He be blessed, it was fitting to give precedence to Shabbat as it teaches us about the glory of Hashem, may He be blessed, and only afterwards present the Mishkan which informs us about the honor of the Jewish people. In addition, based on this order, it is immediately understood that Shabbat sets aside all labor concerning the Mishkan, since which one is set aside for the other—clearly, the smaller matter [Mishkan] before the greater one [Shabbat]. Just as Moshe Rabbeinu honored Hashem by giving precedence to Shabbat prior to the Mishkan, so, too, may our observance of Shabbat give kavod to the Almighty and bring glory to His name. V’chane yihi ratzon. Shabbat Shalom Past drashot may be found at my blog-website: http://reparashathashavuah.org. Please contact me at [email protected] to be added to my weekly email list. *** My audio shiurim on the topics of Tefilah and Tanach may be found at: http://tinyurl.com/8hsdpyd *** I have posted 164 of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s English language audio shiurim (MP3 format) spanning the years 1958-1984. Please click on the highlighted link: The Rav |

Details

Archives

July 2024

AuthorTalmid of Rabbi Soloveitchik zatzal Categories |

- Blog: Rabbi David Etengoff: Parashat HaShavuah

- Sefer Bereishit 5784&5785

- Sefer Shemot 5784&5785

- Sefer Vayikra 5784&5785

- Sefer Bamidbar 5784 &5785

- Sefer Bereishit 5782&5783

- Sefer Shemot 5782&5783

- Sefer Vayikra 5782&5783

- Sefer Bamidbar 5782&5783

- Sefer Devarim 5782&5783

- Sefer Bereishit 5780& 5781

- Sefer Shemot 5780&5781

- Sefer Vayikra 5780&5781

- Sefer Bamidbar 578&5781

- Sefer Devarim 578&5781

- Sefer Bereishit 5778&5779

- Sefer Shemot 5778&5779

- Sefer Vayikra 5778&5779

- Sefer Bamidbar 5778&5779

- Sefer Devarim 5778&5779

- Sefer Bereishit 5776&5777

- Sefer Bereishit 5774&5775

- Sefer Bereishit 5772&5773

- Sefer Bereishit 5771&5770

- Sefer Shemot 5776&5777

- Sefer Shemot 5774&5775

- Sefer Shemot 5772&5773

- Sefer Shemot 5771&5770

- Sefer Vayikra 5776&5777

- Sefer Vayikra 5774&5775

- Sefer Vayikra 5772&5773

- Sefer Vayikra 5771&5770

- Sefer Bamidbar 5776&5777

- Sefer Bamidbar 5774&5775

- Sefer Bamidbar 5772&5773

- Sefer Bamidbar 5771&5770

- Sefer Devarim 5776&5777

- Sefer Devarim 5774&5775

- Sefer Devarim 5772&5773

- Sefer Devarim 5771&5770

RSS Feed

RSS Feed